Everyone wants to be a better shooter. Even the best competitors, sportsmen, and tacticians push themselves to new and better skill. But what happens if you get stuck? What if you go to the range week after week and don’t seem to be improving? What if you aren’t sure your skills are where they need to be? What is a good accuracy standard?

If you’ve been shooting for any length of time, you’ve asked yourself these questions. If you’ve hit a plateau and are wondering how to push your skills to the next level, here are nine possible reasons to consider:

1. You don’t believe you are capable of being skilled

I like to watch gymnastics from time to time, and every time I do, I’m both amazed and a little disbelieving that a human body can achieve such amazing feats. The same can be said of some people who watch exceptionally skilled shooters at their craft. They see people shoot so fast that multiple shots sound like one, do reloads or malfunction clearing so quickly it cannot be processed with the naked eye, or run a course of fire with such precision it almost seems impossible.

While it’s true that we may not all be capable of being the best in the world, we are all capable of being better. You don’t have to be Jerry Miculek to be a more accurate shooter or Ben Stoeger to run a trigger a little faster. We all have room for improvement and that starts by believing that improvement is within our reach, no matter who or where we are.

2. You don’t know what skill looks like

Most people get introduced to shooting sports by family members, watching television, or a vocation that requires carrying a firearm like the military or police. Their metric for skill then becomes either what is common around them or the Hollywood fantastical, and not a whole lot in between. It’s hard to know how to improve if you don’t even know what “improved” looks like.

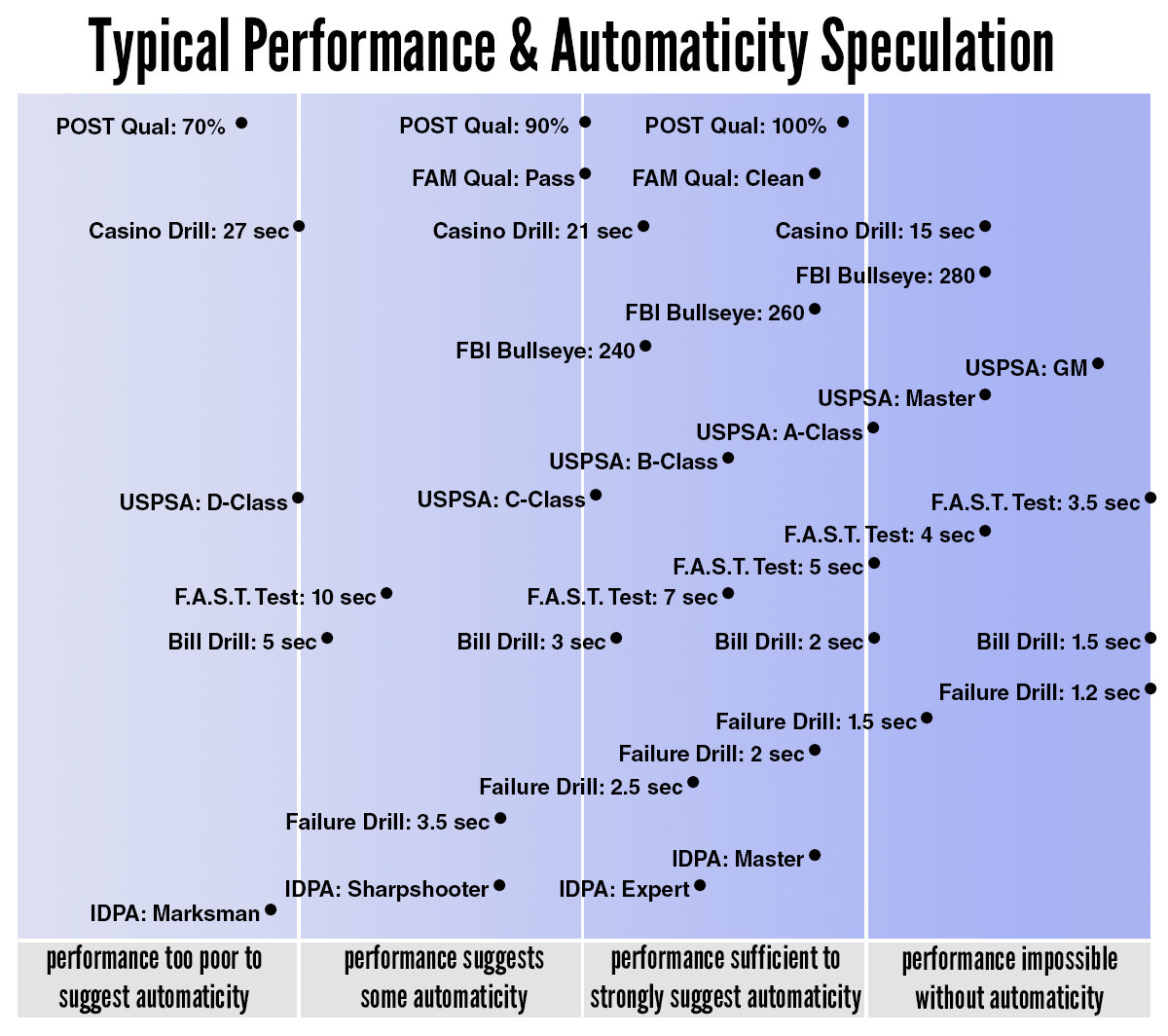

John Hearne addressed that same question several years ago when he started to investigate what real skill looked like based upon his research and the input of other top shooters in the industry. He wanted to lay out what shooting standards suggested a shooter had mastered a certain level of shooting. He compiled his data into a graph he was kind enough to share with me:

Hearne uses the term “automaticity” as it relates to one’s ability to perform certain skills automatically without much thought. One could easily equate one’s ability to perform such standards automatically is indicative of a great level of skill.

Hearne’s standards are broken down as follows:

Novice shooters would be classified as those who shot to a score of 70% or lower on a Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) qualification for their state (the linked qual is for Georgia, but you can search for your own state’s POST course of fire), or someone who classified at a Marksman (MM) in an International Defensive Pistol Association (IDPA) league.

Intermediate shooters are designated those who can run a Casino Drill in 27 seconds or less, those who can classify as D-class in United States Practical Shooting Association, shoot a FASTest in 10 seconds or less, can preform a 5-second or faster Bill Drill or a 3.5 second Mozambique/Failure Drill and classify as an IDPA Sharpshooter (SS).

Advanced shooters should be able to shoot a POST qual of 90% to 100%, pass or achieve a perfect score on the Federal Air Marshal (FAM) course of fire, score a 240 or better on the FBI bulls-eye course, classify as a C or B class shooter in USPSA, shoot the FASTest in 7 seconds or less, shoot a Mozambique/Failure Drill in 2.5 seconds or less, or classify as an Expert or Master in IDPA.

Experts can run the Casino drill in 15 seconds or less, score a 280 on the FBI Bulls-eye, classify as a Master or Grand Master in USPSA, shoot a FASTest in 4 seconds or less, shoot a Bill Drill in less than 1.5 seconds or a Mozambique/Failure in 1.2 seconds or less.

If you’re curious where you stand, pick any one of those drills and run it. Another option is to get involved in shooting clubs that would allow you to classify in IDPA or USPSA.

The website Pistol-Training.com also has many drills and tests that have scores to designate beginner, intermediate, and advanced skill.

Familiarize yourself with what is considered a high level of skill and you can better gauge how far you might need to go.

3. You don’t have a goal

I once spent a few hours on the phone interviewing women about how they came into firearms. One of the questions I specifically asked was whether or not they had any goals regarding their skills. Many of them professed they would like to get better without really defining what “better” meant to them.

This can be complicated by having no real understanding what good skill looks like but also a failure to understand the kinds of goals to achieve in terms of firearms usage.

Goals can range from better accuracy and speed to recoil control or more complicated manipulations. Perhaps the goal is to achieve speed and efficiency in all of those areas. That requires assessing a reasonable standard and setting an obtainable goal.

Your goals might be general (such as obtaining a certain classification in a shooting sport) or specific (decreasing your draw-to-shot time or having faster reloads).

Some reasonable goals that are obtainable for most anyone with diligent work may be the following:

- Drawing from concealment and putting a single shot to the chest box of a man-sized target at seven yards in 1.5 seconds

- .25 second splits (times between shots)

- 2-second or better slide-lock reload from concealment

- Performing a sub 6-second bill drill

Or you can make your own goals based upon your own needs.

4. You don’t have adequate training

There’s a picture of me, somewhere, shooting my first handgun with a tea-cup grip, leaning back so far I’m about to fall over. If that picture could be set to motion, you’d see how horrible my follow-through was. There would be no expectation of any real improvement with this shoddy foundation. I needed real instruction to teach me how to manipulate my firearm properly and efficiently so that I could build on those skills.

Over the years, my instructors have become more specific to select goals I’ve wanted to achieve such as developing speed or increased accuracy.

If you are stalling on the range, it might be because you need an extra set of professional eyes to identify errors and help you improve.

Be picky with your instructor. Find someone who has already achieved your own shooting goals and has produced other students who can do the same. He or she should be skilled at teaching what you want to learn. Take a class, master the fundamentals, set a goal, get to work.

5. You aren’t surrounded with people who are better than you

“If you find yourself the top shooter in your league, range, or club, it probably means you aren’t being challenged anymore.”

It’s satisfying in every way to be the best at something or, at least, better at it than any of your immediate peers. There’s nothing wrong with being proud of our accomplishments, but that pride can often lead people to stop seeking others who can challenge them and from whom they can learn.

If you find yourself the top shooter in your league, range, or club, it probably means you aren’t being challenged anymore. It’s time to find a new group of shooters, club, league or time to entice other, more-skillful shooters to join you.

Find a shooting partner who is better than you and start competing for goals and encouraging or challenging one another. Start looking for other shooting clubs or competing in local, state or national-level matches. Join shooting discussion boards and find other shooters in your area who can challenge you and keep you accountable. At the very least, connect with other skilled shooters via the internet and share drills, ideas and practice times and scores.

Read the works of those who have achieved your goals; follow their blogs, Facebook pages, and public shooting logs if they have them.

There’s always someone better than you.

6. You have poor physical conditioning

You don’t have to be a power lifter to be able to pull a trigger and most manipulations with handguns are more about technique than they are physical strength. However, if you have a real goal of performing to a higher standard with a handgun, physical conditioning will matter, particularly where grip and recoil control are concerned and shooting to high levels of skill for any length of time.

Increasing speed means strength in the hands, arms, shoulders, chest and back. Explosive movement (if action shooting is your goal) requires at least some agility and the ability to move quickly without getting overly winded or shaky. If you don’t already have a fitness plan that works strength, cardio, and flexibility, find one, along with some good nutrition. Your shooting, and probably your waistline, will thank you for it.

7. You aren’t willing to fail

“If you aren’t pushing yourself to failure, you will not push yourself out of your plateau.”

I once had a student who was a very accurate shooter. If given all the time in the world to make her shots, she could get a group most people would dream about. After establishing that she was an accurate and safe shooter, I introduced her to drawing from the holster and pressed her to increase her speed. Her accuracy immediately suffered and she asked me if she could draw from the holster without actually shooting.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because I don’t want to see the holes,” she responded.

“But if you don’t see where you’re impacting, you won’t get better.”

She made a face of disgust and continued shooting, but I understood what was bothering her. She didn’t like to see her beautiful groups opening up when adding new complexities to her skill set. She didn’t want to see her failures.

Here’s a hard truth for you: if you aren’t pushing yourself to failure, you will not push yourself out of your plateau.

If speed is your goal, you have to be willing to push yourself to the point where you are going so fast you are missing. If more complex manipulations are your goal, you will have to be okay with the fact that you may end up fumbling a sequence. It will happen. But without pushing yourself to that point, you will only remain where you are.

Of course, we still must be safe and when the shots matter (such as competition or moments of life/death) we need to stay firmly planted within our skill-sets, but in practice, we need to be comfortable pushing ourselves to failure. If you are comfortable in your practice, you aren’t improving.

8. You aren’t using the proper equipment

One of the best tools I’ve discovered to help me diagnose and correct my own shooting errors has been video. With a video recorder on almost every cell phone these days, the capability to record yourself shooting is accessible to nearly everyone. Video–particularly slow motion video–can be helpful in diagnosing inefficient movement, safety violations, wasted time, bad technique, improper form, and so much more. You can even send that video off to instructors and shooting partners who can give you constructive feedback.

Another under-utilized tool on the range is the shot timer. Without a shot time, you cannot accurately gauge any particular part of your shooting performance whether that is the draw, reloads, split times, malfunction clearances, or transitions from target to target. While shot timers can be pricey, they are worth the investment to help gauge improvement though there are shot timer apps available for both Apple and Android smart phone users that are much cheaper.

It’s also an unfortunate truth that many people are being hindered by their own holsters and guns. Holsters that have retention devices which are not disengaged with the natural draw stroke or hold the firearm in unnatural positions can severely hamper an otherwise speedy draw stroke. Others can have hooks and clips that get hung up on the gun or cover garments. Certain guns may be ill-fitted to the shooter or too big or too little and hold the shooter back from excelling or even enjoying shooting.

9. Your shooting range is inadequate

One of the largest hurdles shooters face in overcoming their plateau is finding facilities that allow them to work their goals in a reasonable and realistic manner. Without being allowed to draw from the holster and put a shot on target under the objective task-master of the shot timer, it’s nigh impossible to gauge any real improvement in that skill. Yet, there are so few facilities that allow drawing from concealment on their ranges. Finding a range that allows the working of those skills can mean extraordinary commute times. Still other ranges actually have limits on how fast shooters are allowed to fire. It’s not uncommon to see ranges that have signs expressly forbidding “rapid fire” even if all of your shots are on target.

If your goal is speed, however, there is the chance that you could be pushing yourself to failure, and if missing is grounds for being kicked off your local firing range, you could see how that would be a problem.

Shooters who are serious about pushing their limits have to then become creative with the places they go to hone their skills. Private pistol clubs and classes become those places supplemented with hours of dry-fire practice.

Many ranges are aware of the limitations they are placing on members and making strides to bridge the gap with skill-building times and small classes geared toward working things like draws from concealment or speed under the watchful eye of an instructor or range safety officer.

If your range does not have such a program in place, consider asking them if they’d be interested in implementing one.

Maximize your potential and break out of your plateau by believing you are capable of real skill, identifying what skill looks like and setting reasonable goals to obtain it. Get the instruction you need, find a good shooting buddy and a good range. Use all of the tools you have at your disposal, and you might just obtain skill you never thought possible for yourself.