The .32 revolver calibers don’t get much attention these days. You may not have even heard of some of them. But today, we’re going to fix that because when it comes to snub nose revolvers, nothing beats a .32. In Part 10 of our Pocket Pistol Series, we’re looking at .32 Short, .32 Long, .32 H&R Magnum, and .327 Federal Magnum.

If you own a snub nose revolver, odds are very good that it’s chambered for .38 Special. Revolvers in general may not be nearly as popular as they once were, but the small, lightweight .38 Special snub nose is still one of the best selling concealable handguns on the market. I like the .38 Special. It’s an excellent round. But for a snub nose, it’s not the best caliber. That title goes to the humble .32.

I should probably be more specific because over the years, there have been many revolver cartridges that fire a .32 caliber bullet. The .32s I have in mind aren’t a single cartridge, but a family of four cartridges: .32 Short, .32 Long, .32 H&R Magnum, and .327 Federal Magnum.

.32 Short, also known as .32 S&W Short or just .32 S&W, was introduced way back in 1878 as a black powder cartridge for small concealable revolvers. Today, we would consider it underpowered, even by pocket pistol standards. But before smokeless powder and 20th century metallurgy, you couldn’t really expect much from a pocket-sized gun and the .32 Short was at least as good as any of its small-caliber contemporaries.

In 1896, the case of the .32 Short was lengthened slightly to create the .32 Smith & Wesson Long. This was the cartridge used for the very first Smith & Wesson hand ejector model which is the basic design that Smith’s revolvers are still based on today. Colt also made revolvers for this cartridge, but they called it the .32 Colt New Police.

.32 Long has a bit more punch than the .32 Short, but it’s still not especially powerful. It is unusually accurate for a handgun cartridge and some small game hunters have made good use of it with wadcutter bullets or handloads. Factory .32 Long ammo is a bit easier to come by than any of the other .32 revolver calibers, partly because of its popularity in international competitive bullseye shooting.

.32 Long was fairly common through the early 1900s but that popularity declined as .38 Special became America’s favorite revolver cartridge. By the 1980s, it was fading into obscurity. But that didn’t stop the revolver manufacturer Harrington and Richardson from trying to bring the .32 back to life. In 1984, H&R teamed up with Federal to launch the .32 H&R Magnum.

Based on an elongated .32 Long case, the .32 H&R Magnum is capable of much higher velocities. Ballistically, it is often compared to standard pressure .38 Special. Harrington and Richardson went out of business just a couple of years after the release of their .32 Magnum, but by then several other companies had adopted the cartridge for their own revolvers. With the improved ballistics, there was a lot of appeal to a small frame revolver that could hold six rounds of .32 Magnum where a .38 or .357 only had room for five.

The new .32 saw some limited success, but thanks to a declining interest in revolvers in general, it never really caught on. By the early 2000s, there were very few new revolvers being made for .32 H&R Magnum.

But the cartridge did have some enthusiastic fans, especially among hand loaders. They noticed that the SAAMI specs for .32 H&R Magnum were fairly conservative and didn’t take full advantage of the case capacity. This eventually led to yet another attempted revival of the .32, this time in 2008 when Ruger and Federal introduced the .327 Federal Magnum. The cartridge case was once again lengthened and the new case capacity allowed for some truly impressive ballistics out of a .32 caliber bullet, even with short barreled revolvers.

But even so, a decade after its introduction, .327 Federal Magnum can only, at best, be described as a mild success. Ruger has been the real champion of this caliber. They’ve offered several revolvers chambered for it including the small-framed SP101 and LCR, a 7-shot GP100, and some of their single action models. At one time or another Smith & Wesson, Taurus, and Charter Arms have also made .327 Magnums, but they have all been discontinued for quite a while now.

Along with a few lever action rifles from Henry Repeating Arms, the .327 Rugers are really the only .32 caliber revolvers in current production that are widely available in the US. Ammo support is minimal, too, with barely a handful of factory loads being produced for the magnum calibers.

And that’s really a shame because together, these four .32 cartridges offer an incredible amount of versatility. As you might imagine from their shared history, the .32s have what the technology world would call backwards compatibility. A .32 Long revolver can also fire .32 Shorts. A .32 Magnum can also fire .32 Shorts or Longs, and a .327 Magnum can safely chamber all four. So a .327 gives you the most versatility but even a .32 Magnum offers some advantages over the more ubiquitous .38 Special.

In fact, if we overlook the lack of industry support and availability for a minute, the .32 family of cartridges is a much better fit for a small revolver than any other caliber. Besides squeezing one more round in the cylinder than a .38 or .357, the .32s are just a lot more shootable, especially in a lightweight model.

I think some of the best .32s ever made were the .32 Magnum Smith & Wesson Airweight and AirLite J-frames from the late 90s and early 2000s. This is a Model 332 Ti. It’s got an aluminum frame and a Titanium alloy cylinder for an unloaded weight of just 11.5 ounces. That’s about the same weight as this Model 442 PD in .38 Special or the model 43C in .22 LR. The .38 is pretty obnoxious to shoot, even with standard pressure ammo. The 43C is a great shooter except for the heavier trigger pull you get with the rimfire guns. With the 332, I can load up .32 Shorts and the recoil is about the same as the .22 LR. Shooting the more common .32 Long ammo is on par with the mild recoil of a .22 Magnum and even if I load up full power .32 Magnum self-defense loads, it’s still a softer shooting gun than this .38 with almost any factory load you’ll find.

This isn’t just about comfort. Like I’ve mentioned several times previously in our pocket pistol series, less recoil almost always results in better shot placement. In the context of self-defense, good shot placement beats good ballistics. With small handguns, we usually have to pick one or the other, but .32s can offer a very nice balance of both: mild recoil and decent ballistics.

Felt recoil is always a difficult thing to quantify but I’m going to do my best by sharing the results of a timed shooting drill I tried at the range with eight different types of ammo. I used two nearly identical 17-ounce Ruger LCRs. One chambered in .357 Magnum and the other in .327 Magnum.

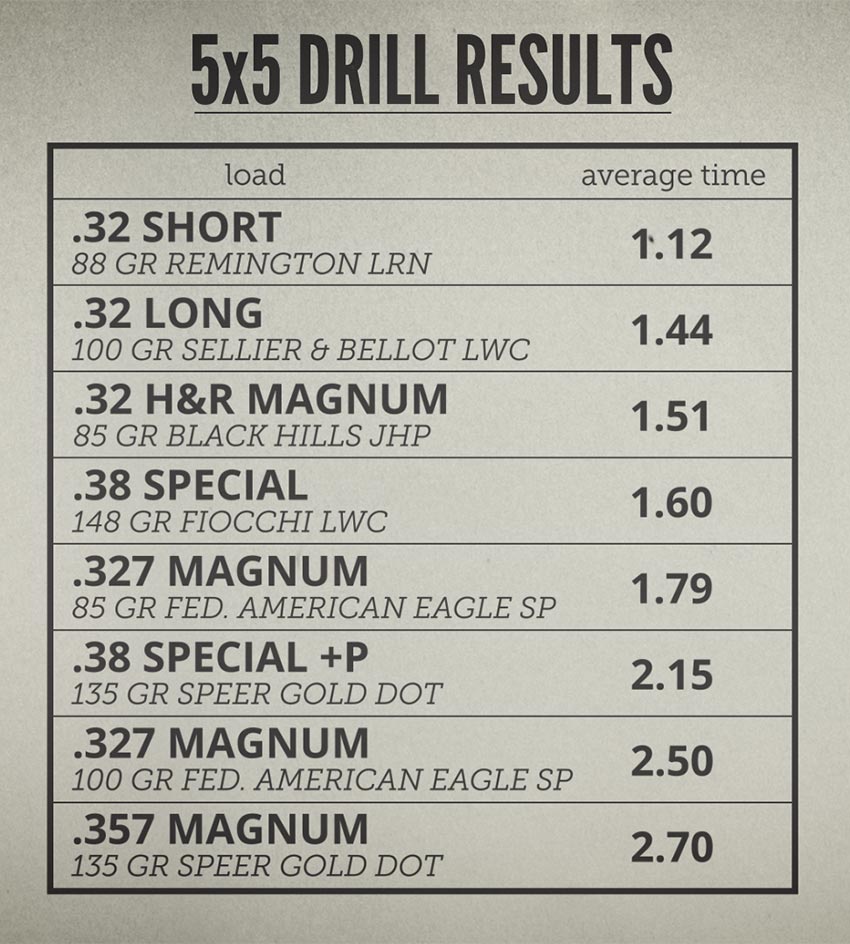

I chose the 5×5 drill to evaluate the effects of recoil. Normally, the goal of this drill is to fire five rounds into a five-inch circle from five yards in under five seconds starting either from the holster or a low ready position. But for this exercise, the time to the first shot wasn’t important — I was only interested in how quickly I could recover the sights from recoil and fire the next shot. So I attempted the drill four times with each load and for every attempt, I recorded the time between my first and last shots. And here’s the average time of my two fastest clean runs from each load:

Keep in mind, this is not a perfect numeric representation of the felt recoil from these loads, but it should give you a basic idea of how they compare to each other. The .32 Long and .32 Magnum, for example, are both light recoiling rounds, but in reality there is probably a slightly bigger difference in felt recoil than these numbers suggest. The .38 Fiocchi Wadcutter is the absolute lightest recoiling .38 Special commercial load that I’m aware of and I still shot the drill slower with that than with the .32 Magnum.

The .327 American Eagle 85-grain soft point is actually considered a low recoil load for .327 but it’s still quite a handful. I think this would be great for a steel gun like the SP101 but not my favorite load to shoot out of the LCR. I shot the .38 Special +P Gold Dot much slower than the 85-grain .327, but I think the felt recoil was actually pretty similar between the two.

Shooting the full power 100-grain .327 Mag American Eagle out of a 17-ounce revolver is just painful and very loud and not something I would recommend. Even if you’re immune to the pain, keeping the muzzle on target is a real challenge with a load like this. And then finally, the 135-grain .357 Magnum Speer Gold Dot is the short barrel load which is actually quite mild for a .357 but still, it sucks to shoot in the LCR, and it’s every bit as difficult to control as the .327 Magnum.

Again, this is not a perfect proportional scale, so take these numbers with a grain of salt. The bottom line is that if you’ve got a .32 revolver, anything you can fit in the cylinder other than the .327s is going to have lighter recoil than even the lightest .38 Special. These little guns are actually fun to shoot with .32s.

So now let’s take a closer look at the terminal ballistics. Unfortunately, the fact that .32s aren’t very popular means we have little information to go on as far as how these calibers compare to others in actual shootings. Even when a .32 does show up in the news or a police report from a self-defense shooting, they often don’t even specify whether it was a .32 Short, Long, Magnum, or .32 ACP. I don’t like relying on ballistic gel test data without the ability to compare it to what’s been observed in the real world, but it should still give us a decent idea of what to expect.

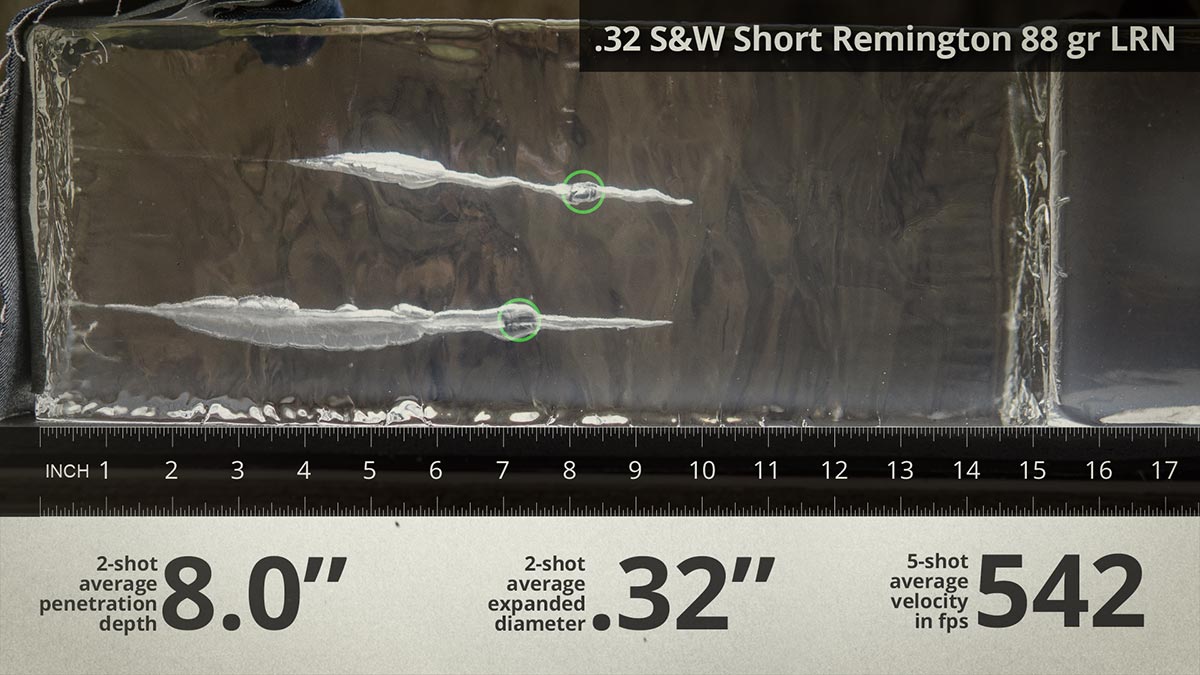

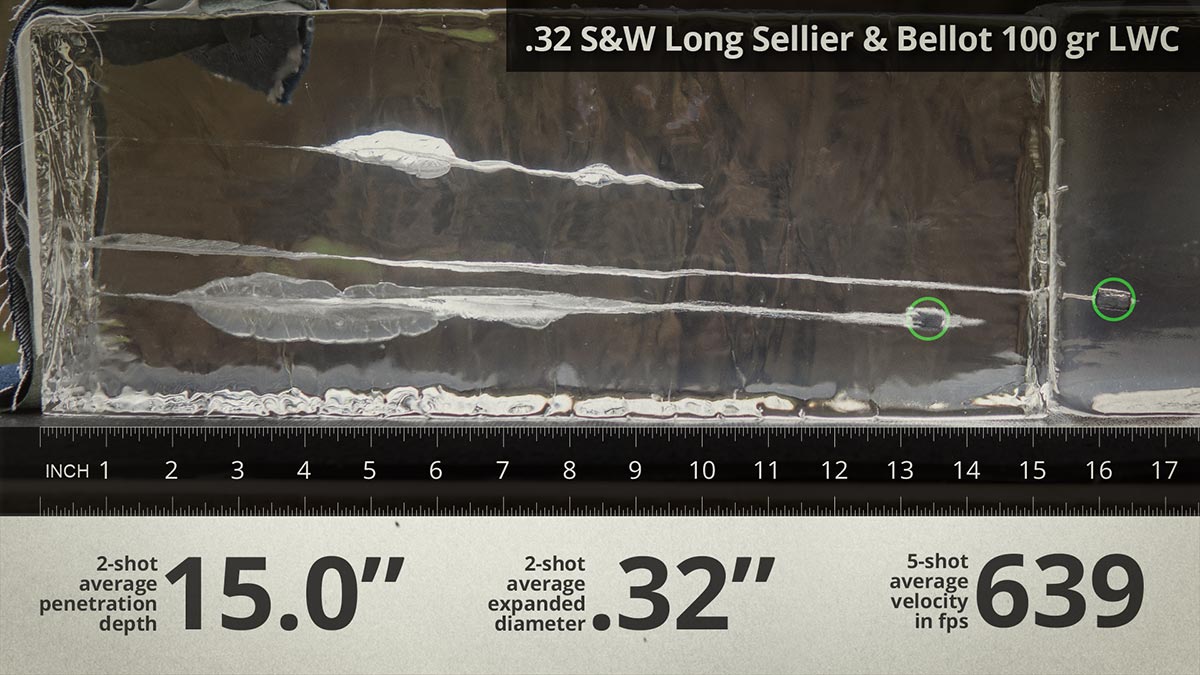

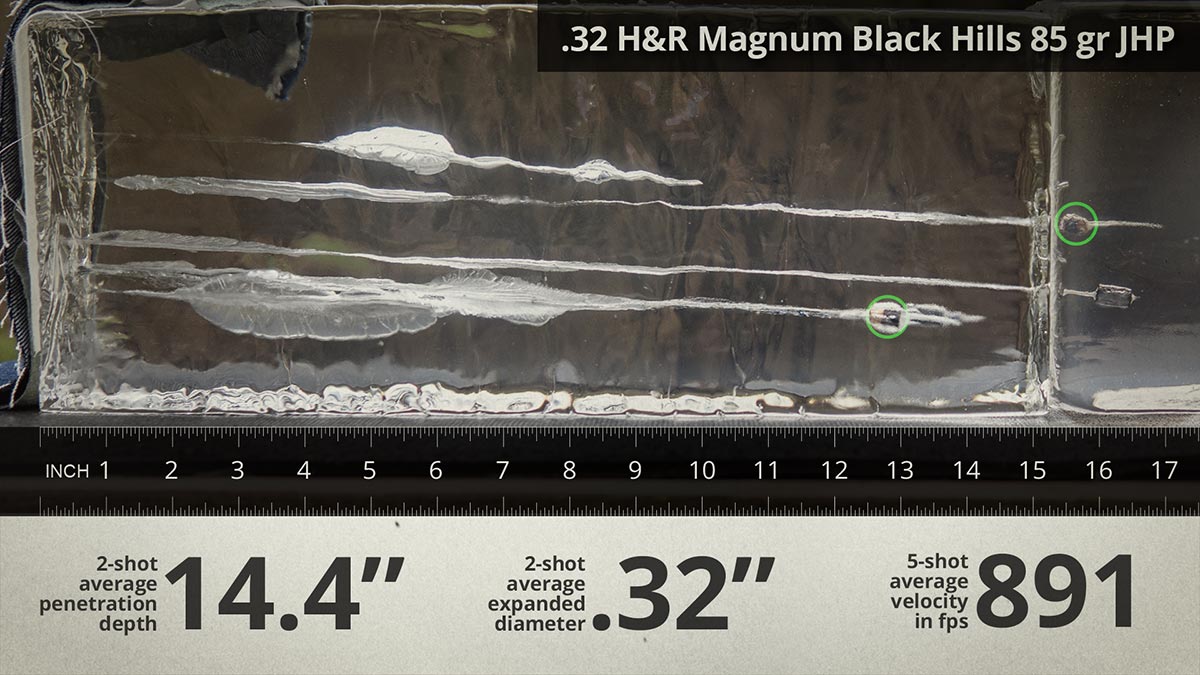

As with the other calibers I’ve covered so far in our pocket pistol series, I will be doing a more comprehensive gel test for the .32s later on. For today, I’ve got a quick overview. I fired two rounds of each of the .32 revolver calibers into a single block of gel with our four-layer heavy clothing barrier.

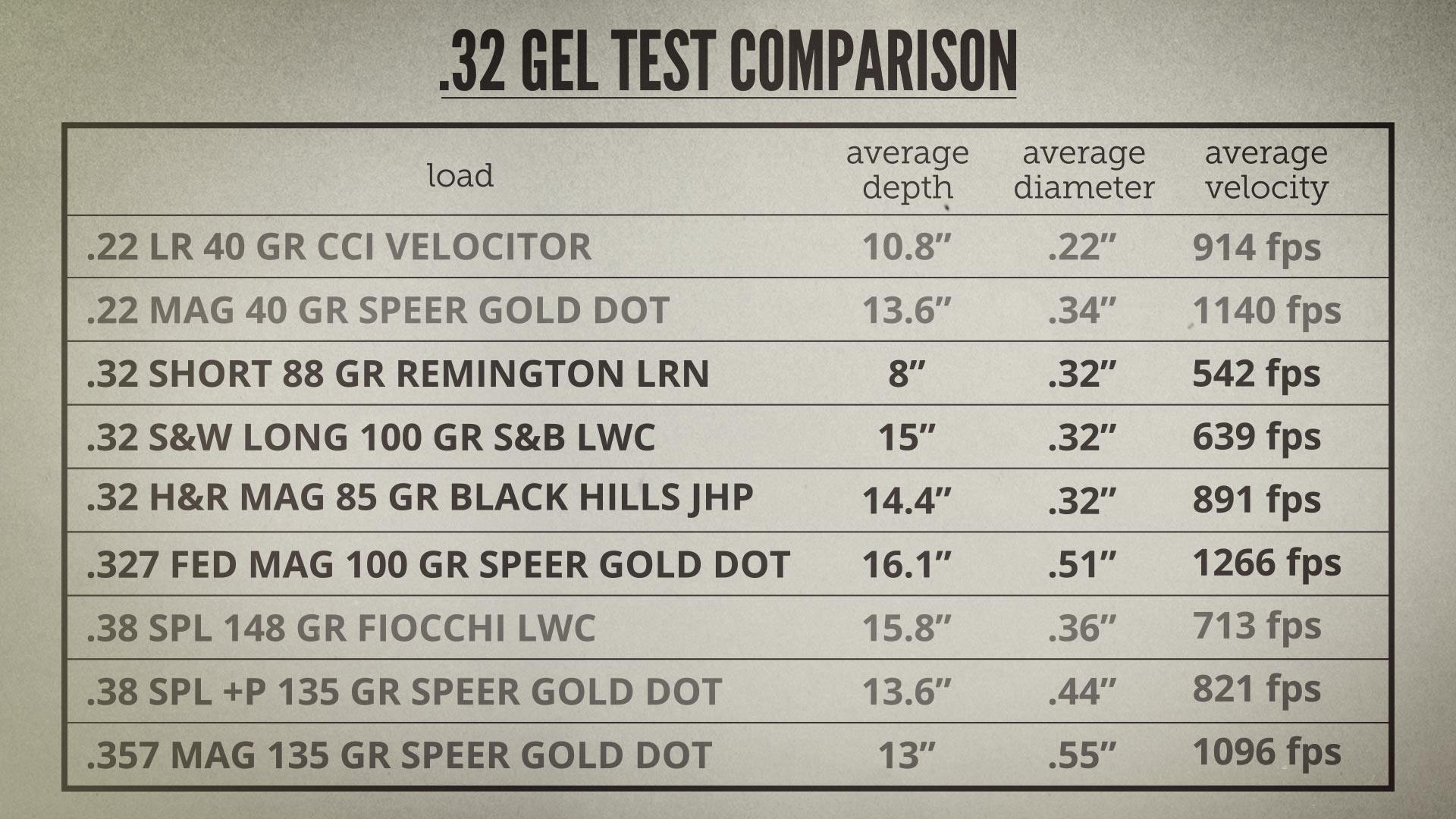

The .32 Short 88-grain Remington bullets averaged around eight inches of penetration. They actually made it a couple of inches farther, but there was an unusual amount of bounceback. Either way, they landed well short of the ideal 12-inch minimum.

The .32 Long Wadcutters really surprised me with an average penetration depth of 15 inches. That is roughly the same performance as the Winchester .38 Special wadcutters we tested a while back, which is a heavier bullet with more velocity. Full wadcutters are known for having excellent penetration, but this was still unexpected for a load this slow and light.

The Black Hills .32 H&R Magnum Jacketed Hollow points averaged 14.4 inches in gel. Neither of them expanded, which is not unusual for a small caliber hollow point at this velocity.

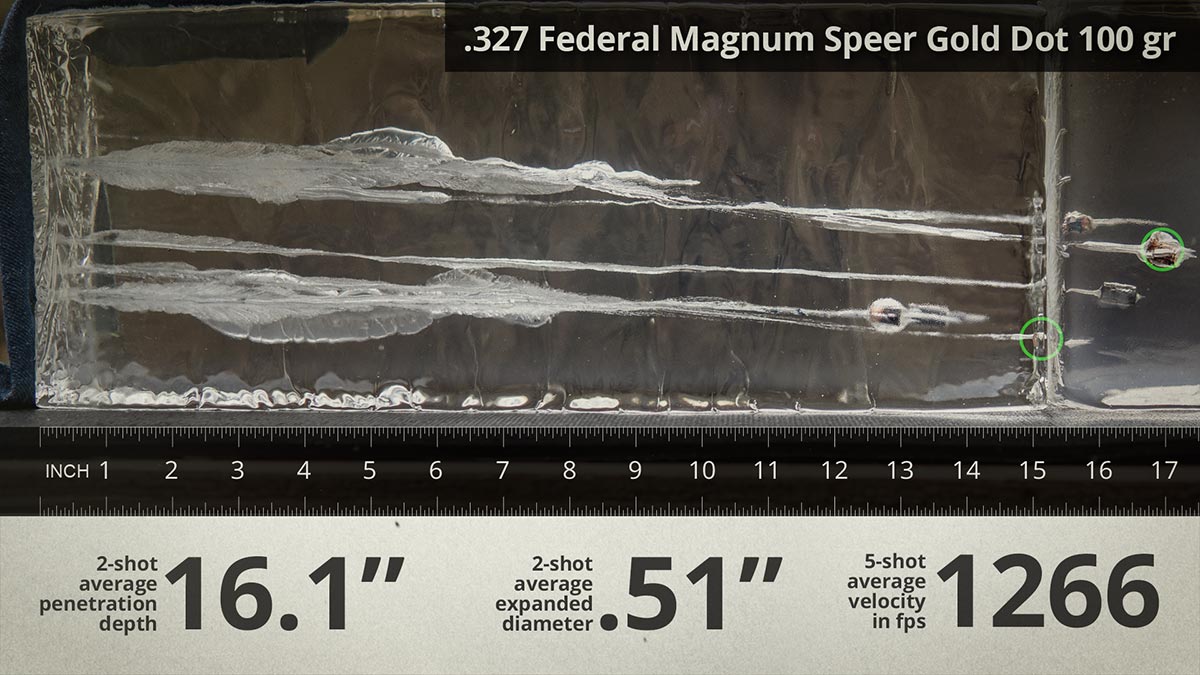

Finally, the .327 Magnum Speer Gold Dot delivered some harsh recoil but performed exactly as advertised. Average penetration was 16.1 inches and both bullets expanded nicely to .51 inches.

Let’s see how these results compare to some other calibers. The .32 Short obviously doesn’t look good compared to much of anything. The other .32s aren’t bad at all. Penetration is more than adequate, and that’s the first priority. Expansion is non-existent except for the .327, but even in a .38 +P, expansion is unreliable with a 2-inch gun. For as little recoil as the .32 Long and H&R Magnum deliver, this is impressive ballistic performance.

So really, the only catch preventing a .32 from being the ideal caliber for a snub nose is the lack of industry support. Ruger is making the .327 revolvers I mentioned earlier but if you prefer a Smith, you’ll have to hunt down a used one and they are pretty rare.

The availability and pricing of .32 ammo is mixed. .32 Long is the most common and the most affordable, but expect to pay about 30% more than .38 Special for everyday target ammo. And there’s a similar price jump when you go from .357 Magnum to .327 Federal Magnum. .32 H&R Magnum is my favorite of the .32s but it’s also the hardest to come by. Factory target ammo is non-existent. Right now, the only options in that caliber are premium self-defense loads from Federal, Hornady, Black Hills, and Buffalo Bore.

Also, keep in mind that the ammo market is slower right now that it was earlier in the decade. If demand were to spike again like it has in the past, ammo manufacturers are going to focus on cranking out the most popular products. The more off-beat calibers can become even more scarce during those periods until things cool off again.

So for inexperienced or casual shooters or anyone who only plans to own one snub nose revolver, it’s probably best to stick with a more mainstream caliber with better availability and industry support. But if the ammo issues don’t bother you, the .32s have a lot to offer. In particular, the Ruger LCR in .327 Magnum is a near perfect all-around snub nose revolver. It’s light enough to be easy to carry but it’s still got enough heft to be pleasant to shoot for long range sessions. It’s an approachable gun for a novice shooter to learn on and it offers a lot of flexibility for more experienced revolver fans who actually like to shoot their snubbies.