Pocket pistols and revolvers chambered for the humble .22 LR are easily dismissed as carry guns suitable only for novices and the elderly. While there are some definite drawbacks to relying on a small gun that fires small bullets for self-defense, it also may have significant advantages that even skilled and experienced shooters can benefit from.

Details in the video below, or scroll down to read the full transcript. If you’re just now joining us, be sure to check out the rest of our Pocket Pistol Series.

It’s been said that .22 LR has killed more people than all other calibers combined. I don’t know where this idea comes from, but it’s stupid and people should stop saying it. Whether or not it’s true, it has nothing to do with the goal of personal protection. What we care about is having the ability to immediately change the behavior of the person who is trying to kill us. Or, as Claude Werner put it back in part 1 of this series, we want to “force a break in contact with the enemy.” So today, the question we’re asking asking is whether a pocket-sized handgun chambered for .22 LR is a wise choice for that task.

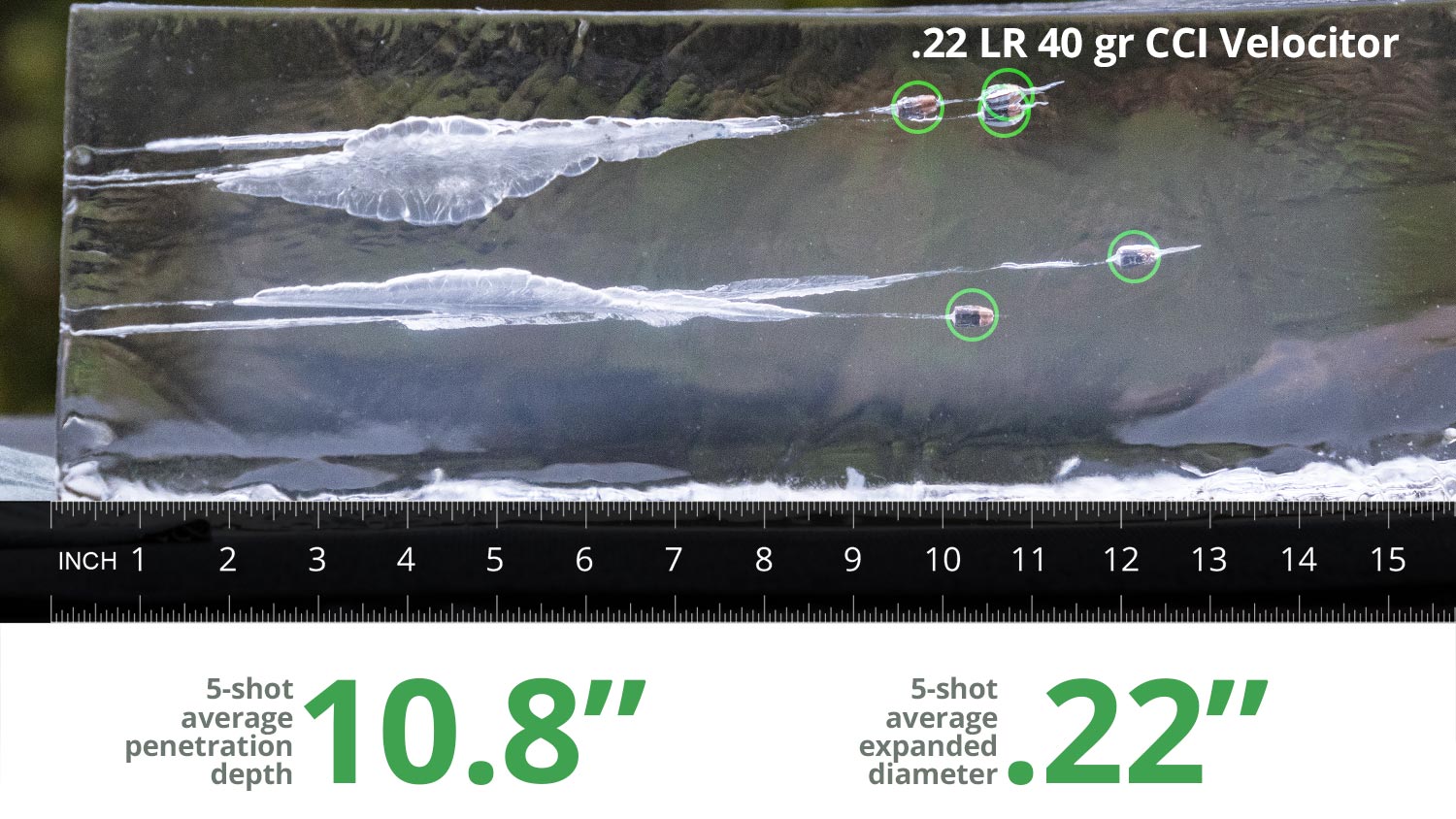

From a standpoint of terminal ballistics, .22 LR is not all that impressive, especially when fired from a short handgun barrel. But it’s also much more capable than a lot of people give it credit for. We’ll be doing some extensive velocity and ballistic gel testing with different .22 loads sometime in the not too distant future. For now, just to illustrate the point, I ran one quick gel test with the CCI Velocitor 40-grain small game load that’s been known to perform relatively well out of handguns.

Using a 1.9-inch snub nose revolver, all five rounds penetrated between 10 and 12 inches. There was no expansion, but we don’t really expect a .22 to expand. Penetration is by far the more important attribute. The FBI uses a minimum standard of 12 inches of penetration for duty ammo but 10 inches is nothing to sneeze at.

With good shot placement, a bullet from a .22 handgun should be more than capable of reaching the vital organs to physically disable an attacker. But whenever possible, we always want to corroborate gel test results with what has been observed in real world use.

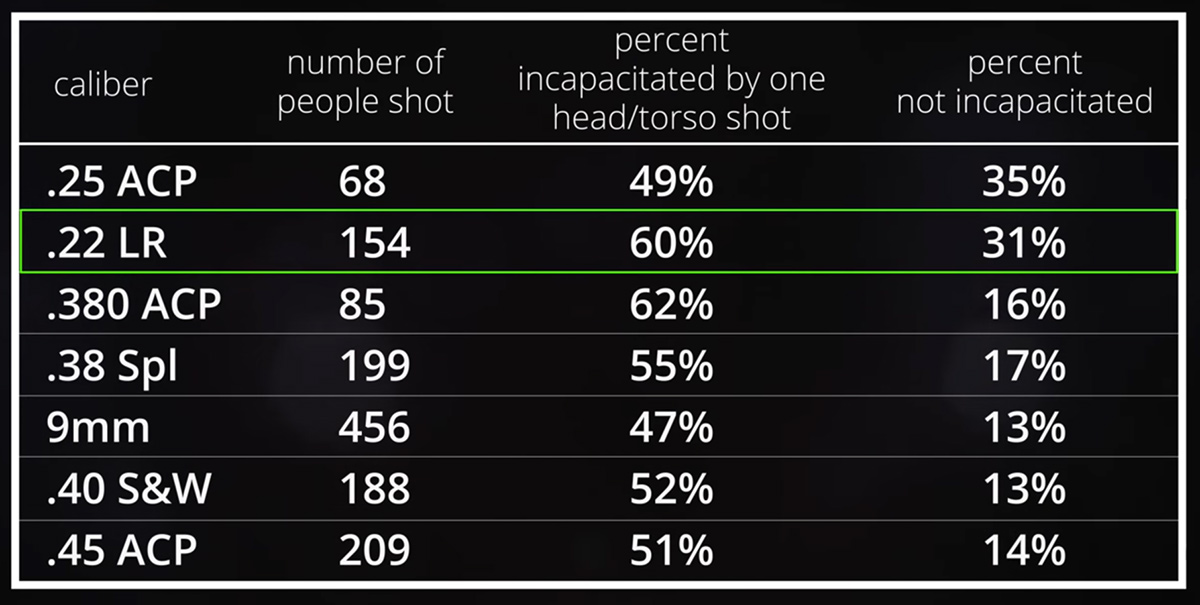

Let’s take a look at some more numbers from Greg Ellifritz’s Stopping Power study based on statistics from 1800 shootings. He found that about 60% of the time someone was shot with a .22, they were incapacitated after a single hit to the head or torso. That’s on par with the numbers from some much bigger and more powerful calibers. But about one third of the time, someone hit with a 22 was not immediately incapacitated no matter how many times they were shot. That’s roughly twice as many failures as calibers of .380 and up.

Last week, I talked about .25 ACP and how, despite a less than stellar street record, there’s a case to be made for carrying one; .25s are smaller than any other pistols out there and there might be some niche uses for something like that. That’s not the case for .22 pocket guns. There are really only two .22 LR semi-autos in current production that I’m aware of that could properly be considered pocket pistols: the Beretta 21A Bobcat and the Taurus PT22. They are very similar pistols in appearance and they are about the same size and weight. Neither of them are easier to carry than the typical polymer .380 pocket pistol like this Ruger LCP II. Actually, the 22s are much wider in the grip than any modern .380 ACP.

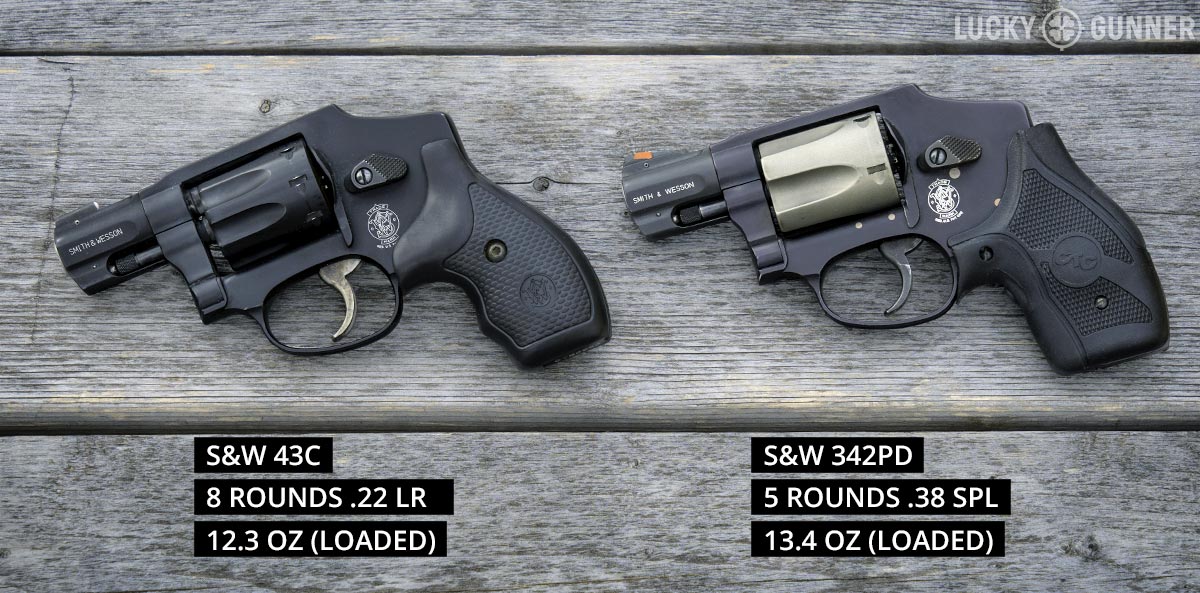

The situation is similar with lightweight revolvers like the two Smith & Wesson J-frames I’ve been working with lately. The Model 43c weighs 12.3 ounces loaded with eight rounds of .22 LR, but that’s only one ounce less than the Model 342PD which is identical in size, but chambered for .38 Special.

So a .22 offers little to no advantage in size or weight and it’s less effective in terms of terminal ballistics.

Of course, the real reason we all like .22s anyway is because of the low cost of ammo and the low recoil. Even out of these really tiny guns, the recoil is so mild that even the most timid shooters are usually not bothered by it. That’s why 22 pocket guns are sometimes recommended for inexperienced shooters who don’t practice very often or for people with physical limitations like arthritis, tendonitis, or diminished grip strength.

A .22 might be a good solution for some of these people, but I wouldn’t be too quick to make that recommendation. Most of these .22 pocket guns are double action designs, which means the trigger pull is relatively heavy. They actually tend to be even heavier triggers than double-action centerfire pistols because the rimfire primer requires a bit more force to ensure reliable ignition. It’s a real challenge to get accurate hits on demand with a trigger like that without some good coaching and a fair amount of practice. A lot of people with hand-related health issues are going to have trouble pulling the trigger at all.

There’s no way to get around the fact that tiny guns are difficult to shoot well, even when they don’t have a whole lot of recoil.

Having said all that, I think it’s a mistake to dismiss the .22 pocket pistol as a gun that’s just barely “better than nothing.” It has some benefits, even for proficient shooters who don’t have any medical limitations.

Think about it this way — most of us who are serious about practicing our handgun skills on a regular basis tend to do the vast majority our shooting with a full size or a compact pistol chambered for a service caliber. That’s where we dedicate most of our training hours and our ammo budget. If we own a little pocket pistol that we carry occasionally, we probably don’t get a whole lot of trigger time with it. They are not much fun to shoot, and to be honest, when you’ve been blasting away with a full size gun for an hour, it is kind of a hit to the ego to pull an LCP or a J-frame out of the range bag and find that your speed and accuracy are almost cut in half.

Some of us still train diligently with these lightweight .38s and .380s anyway, but it always feels kind of like taking medicine.

Now, what if that pocket gun was a .22 instead? Because the ammo is so cheap, you could run 50 rounds through it at the end of every range session and only be out two bucks. Over time, you would probably get really good at shooting that little gun, and you might actually enjoy doing it.

A lot of people adopt a training strategy like this, but they use the .22 as a dedicated training analog for an identical gun that’s chambered in a larger caliber. I think that strategy can work well, but speaking just for myself, no matter how many rounds I put through J-frame snubbies, I will never shoot a lightweight .38 as well as I shoot the .22 LR.

How much better does our performance with the .22 have to be before that outweighs the ballistic advantage of carrying a centerfire pistol? To be completely honest, I don’t really know how to answer that, but I think it’s worth thinking about. It probably wouldn’t be a bad idea to start with some objective way to measure your performance like one of the drills or tests from our Start Shooting Better series. If you’re limited to carrying a pocket pistol for whatever reason, and you can score significantly better on a shooting drill with a 22 than you can with a centerfire, I wouldn’t try to talk you out of carrying the .22.

But we actually might be getting a little ahead of ourselves. Before we even get to the point of measuring skill, our first priority in a carry gun should be reliability. The gun has to work. And everybody “knows” that .22 Long Rifle is inherently unreliable compared to modern centerfire ammo. Or maybe that’s another aspect of this cartridge that has been greatly exaggerated. We are actually doing some testing on that very topic right now so next time, we’re going to continue this discussion and take a closer look at whether .22 LR is reliable enough for personal protection. Be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss that, and if you want to support our pocket pistol series and other videos, get your ammo from us with lighting fast shipping at LuckyGunner.com.