This is everything (at least the first half of everything) you should and would ever want to know about using buckshot in a home-defense shotgun. In this, the first of a two part series, we’re covering topics from the absolute basics to some of the more obscure aspects of buckshot. Watch the video below to get all the details, or just scroll down to read the full transcript and learn about buckshot sizes, patterning and more.

Exploring Buckshot

If you have a shotgun for defending your home, it should probably be loaded with buckshot. I’ve already done a video about choosing buckshot for your home defense shotgun, but that’s been almost five years ago now and it was kind of short. I wanted to revisit the topic and fill in some of the details I left out before. This is going to be a pretty deep dive because buckshot is a surprisingly complex topic. There are a ton of options out there and more than any other type of firearm, ammo selection for shotguns is critical for making sure that gun does what we want it to do.

If you’re watching this because you just want an easy recommendation for buckshot to put in your home defense gun, I’ll save you the trouble of sitting through the whole thing. Just get a few boxes of 12 gauge Federal FliteControl 8-pellet #00 buckshot. It works great in almost any shotgun and makes one big fist-sized hole out to at least 10 yards. There are other good loads out there, but it’s hard to go wrong with FliteControl. Now do me a favor and go buy it from LuckyGunner.com because my kid is gonna need braces soon.

Okay, if you’re still with me, I’m assuming that means you want to know more about the “why” behind that choice. So I’m going to go over just about everything you could want to know about using buckshot for self-defense. I’m splitting this one into two videos. I’ve got three main points to cover today and I’ll do three more in part 2.

One last thing before I get into it. I don’t usually do this, but there’s a question that comes up fairly often and it’s a valid one. “Who is this guy and why should I listen to anything he has to say? He looks like he might even be a vegetarian. What could he possibly know about shotguns?”

Why Should I Listen To You?

I actually wish people would ask this more often, especially when they get their gun information from YouTube. I’m nobody special. I’m employed by LuckyGunner.com to provide information that is useful (or at the very least, entertaining) for our customers and potential customers. To that end, I have received roughly 700 hours of professional firearms training over the past several years. About 100 hours of that has been shotgun-specific training including classes with Rob Haught, Darryl Bolke, Randy Cain, Tim Chandler, Ashton Ray, and the Rangemaster Shotgun Instructor Course with Tom Givens.

I certainly don’t claim to speak for any of these instructors. I recognize there is going to be room for disagreement with some of the ideas I’m about to bring up. But I believe strongly in an evidence-based approach to studying these issues. So if I say something that sounds a little off to you, I very well might be 100% wrong. But I hope you’ll consider the fact that I probably didn’t just make it up. It’s either based on something I’ve observed or something I’ve learned from people who have a lot more experience with this stuff than I do.

Also, I’m not a vegetarian.

1. Buckshot Sizes and Types

With that out of the way, let’s start with the non-controversial stuff. The first thing you should know about buckshot is that there are a lot of different types and they are not all created equal. That probably goes without saying if you’ve been around shotguns for a while, but not everybody knows that. Buckshot varies in terms of the length of the shell itself and the number, size, and velocity of the pellets in that shell. Ammo makers also have a variety of different methods of trying to control the spread of the pattern, and that’s something we’ll come back to in part 2. First, let’s break down those other attributes:

By the way, just assume I’m talking about 12 gauge here. There’s nothing wrong with 20 gauge in theory, but it has just a fraction of the market support 12 gauge does. There are not many purpose-made self-defense loads for 20 so our focus here is on 12.

12 Gauge Shell Length

There are four common sizes: 2¾-inch, 3-inch, 3½-inch, and recently we’ve been seeing more of the 1¾-inch mini-shells.

The 2¾-inch shells are standard. There’s normally not any good reason to use anything other than a 2¾-inch shell for self-defense against humans. They are plenty sufficient for that job. The mini-shells don’t feed in most shotguns. You can only use the 3 and 3½-inch shells if your barrel explicitly says it’s chambered for them. Those longer shells will give you more velocity or more pellets. That might be useful for larger animals or for extending your range, but for the average person, that’s not really necessary for personal protection in and around the home.

Shell length is determined by measuring the shell before it’s crimped. A loaded shell out of the box is a little shorter. So, if you pick up a 2¾ inch shell after it’s fired, it will measure about 2¾ inches. When it’s unfired, it will actually be closer to 2¼ inches if it’s got a star crimp. If it’s roll crimped like this, it’ll be more like 2½ inches. That means for some shotguns, you won’t be able to fit as many shells in the mag tube if they’re roll crimped. You might only get four shells in a five-shot tube. Most shells designed for self-defense are star crimped to maximize your capacity.

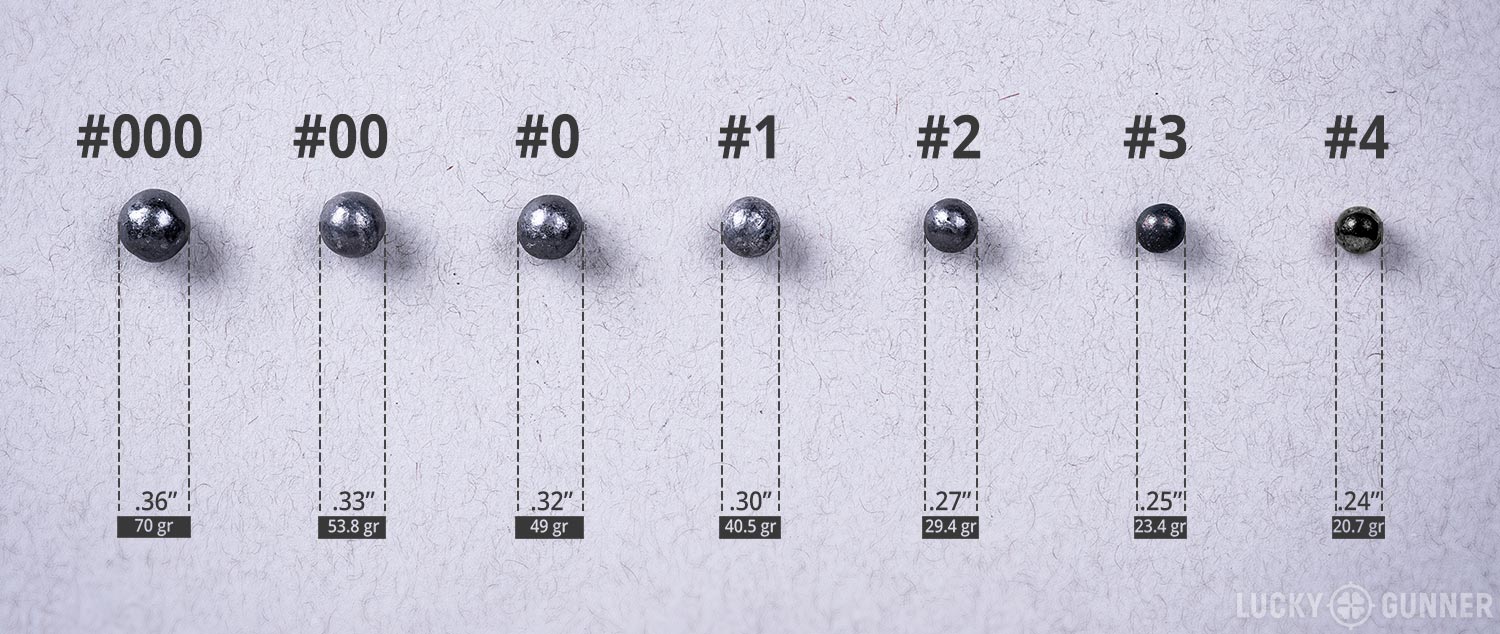

Buckshot Sizes

The smallest buckshot is #4 buck, not to be confused with #4 shot, which is birdshot. The largest I’ve heard of is #0000 buckshot but #000 is the largest common size. The most popular size by far is #00 buck, especially for self-defense. It’s been the gold standard for law enforcement for many decades. #1 and #4 buck are also fairly common. Each pellet of #00 is about .33 inches in diameter. #1 is .30 inches and #4 pellets are .24 inches.

Number of Pellets

The number of pellets in each shell will vary depending on the size of the shot and the length of the shell. 2¾-inch #00 buckshot comes with either 8 or 9 pellets. Occasionally you’ll see a 12-pellet load. #1 buck usually has 12 to 16 pellets. #4 will have around 21 to 28 pellets.

Buckshot Velocity

Like I mentioned, some of the 3 and 3 ½-inch shells will push the pellets faster, but even among the 2 ¾-inch shells, the velocity might vary quite a bit. For self-defense loads, that window is typically between about 1100 and 1600 feet per second out of the manufacturer’s test barrel.

So how much velocity do you need for self-defense? Well, it depends. The loads around 1100 or 1200 feet per second are often labeled as “low recoil” and they are a bit easier to control. Low recoil #00 buck has been very popular with law enforcement since the 80s or 90s and it seems to be just as effective for close range encounters as the higher velocity stuff. Just be aware that certain semi-auto shotguns don’t cycle reliably with low recoil loads.

At roughly 1100 to 1200 feet per second, #00 will penetrate 18 to 20 inches in ballistic gel, which is more than enough. If you push those same #00 pellets 33% faster at 1600 feet per second, you’re probably going to end up with over-penetration. They’re also more likely to penetrate exterior walls and other hard barriers.

#1 & #4 Buckshot

#1 buckshot also does really well in that 1100-1200 foot per second range. That gets around 15 to 18 inches in gelatin which means it’s not as likely to pass completely through a human target.

Honestly, #1 buckshot is really more ideal than #00 from a ballistics standpoint. It has just as good of a success rate with law enforcement. Unfortunately, #1 is just not as popular. So market demand is low, making it hard to hard to find good loads with that shot size.

#4 buck is where you might want some extra velocity. Each #4 pellet has about half the mass of a #1 pellet. So, if it’s moving at the same velocity as the #1, it’s probably going to under-penetrate. Most of the #4 loads are more like 1300 or 1400 feet per second. Even then, they are just on the very edge of adequate penetration, at least anecdotally speaking. I’ve heard of plenty of success stories with #4, but I also know of a couple of failures to stop that probably would not have been failures with a #00 or a #1 buck. At close range, inside a home with nothing in between the gun and the threat, it’s probably fine.

I could see a #4 buck being a decent choice if you’re in an apartment or a townhouse or something and you want to minimize penetration through walls. It’s still going to go through at least a couple of interior walls just like anything else that will reliably stop an attacker. It just might not go through all of the walls in your apartment building. So… don’t miss.

2. Buckshot Patterning

And that brings us to the number two thing you should know about buckshot: You have to pattern your buckshot. Patterning just means that you fire a couple of rounds at various distances to see what that load does in your gun. The goal is to find out how much the pellets spread at any given distance.

Think about whatever area you might have to defend from people or animals or whatever. Find the longest possible shot you would have to take. Think in terms of a potential lane of fire, not just the size of a single room. Inside your home, that might be from the back of a bedroom, down the hall, through the kitchen to the back door. Pace off that distance and add a couple of yards just to be on the safe side and use that as your maximum distance. Start patterning your buckshot at about five yards, and repeat the process at three to five yard increments until you reach that maximum distance. That way, you know exactly when that shot starts to spread and how big the pattern is going to be.

The key is predictability. You have to know how your buckshot behaves. And every barrel is a little different, so you have to pattern it in your specific gun.

3. Smaller Patterns are Better

So what kind of pattern do we actually want? That’s the third thing you need to know about buckshot: A small pattern is usually better.

By “small,” I mean less than about five or six inches across at your maximum distance. Maybe even less than that if possible. For one thing, the terminal ballistics are better when the pellets all impact the same general area at once. But the main advantage of a small pattern is shot accountability.

We are accountable morally, ethically, and legally for every projectile that leaves that barrel. The wider the spread, the greater the chance that even a good center hit is going to result in at least one or two pellets that miss the target and hit something we did not intend to hit. Unless you live alone and don’t have any neighbors, that’s not acceptable.

Tim Chandler, who teaches some excellent shotgun classes, has often pointed out what I think is a perfect illustration of the problem with wider patterns. When they start picking up the pace in their classes, most people’s accuracy suffers a little bit. That’s pretty normal. But the students with wide-patterning buckshot often struggle to keep all of their pellets on the target. Even at just 10 yards, they’ll have half their pellets on the target. Half of them miss the paper completely. The students with tighter patterning buckshot might have some pellets hit where they didn’t quite intend, but the whole pattern will be on the target. They’re still hitting the threat somewhere with every pellet.

The way Tim puts it is that even though it’s counter-intuitive to the way we often think about shotguns, a wider pattern means you have to be more or less perfect when you mount the gun, sight it, and press the trigger. A tighter pattern is more forgiving of some small mistakes in your shooting technique.

I’m not saying you need a three inch pattern at 20 yards if the maximum range in your place is something like five yards. It’s context-dependent. The greater that maximum potential distance is, the more that shot spread becomes a major liability.

Now, not everyone agrees with this approach to shotgun ammo selection. There are definitely some different ways of looking at it. I think I can predict at least two or three of the objections. Like, “isn’t the whole point of using a shotgun so you have a better chance of hitting your target with a wider pattern?” Or, “if you want such a tight pattern, why don’t you just use slugs? Or for that matter, why not an AR or some other carbine?”

All very good questions, and I’ll do my best to answer each of them in part two. My hope is this first part served as a good tutorial of the basics. Well be referring back to principles like buckshot size and patterning as we explore shotgun shells further next time.