As I was planning future installments of our Pocket Pistol Series, I realized that several of the upcoming caliber-specific discussions would need to include references to the Smith & Wesson J-frames and the Ruger LCR snub nose revolvers. Rather than forcing our viewers/readers to suffer through multiple repetitions of a basic “J-Frame vs LCR” comparison, I decided to dedicate this installment of our series to that topic so that I could simply refer back to it as needed. It turns out there was a lot more information to cover here than I initially thought, and there is still plenty more that could be said. If you’re in the market for a snub nose (whether it’s your first or your 20th), I think you’ll find something useful here.

Details in the video below, or scroll down for the full transcript.

It’s Part 6 of our series on pocket pistols and other ultra-concealable handguns and we can’t talk about pocket pistols without giving some special attention to the snub nose revolver. In particular, I want to compare two of the most popular types of snubbies on the market: the Smith & Wesson J-frame and the Ruger LCR.

The first member of the J-frame family came in 1950 with the advent of the Smith & Wesson Chief’s Special, later called the Model 36. It was a steel frame, 5-shot .38 Special available with a blued or nickel-plated finish.

Over the years, Smith & Wesson has produced hundreds of variants of these small revolvers chambered in numerous cartridges, made from different materials with all kinds of finishes, barrel lengths, sights, stocks, and dozens of other options. Smith & Wesson’s catalog currently lists 52 variants of the J-frame but the most popular is probably the aluminum-framed Airweight 642.

The original Ruger LCR or “Light Compact Revolver” debuted just a few years ago in 2009. It’s a double action only 5-shot .38 Special intended to compete directly with the Smith & Wesson Airweights. The frame of the LCR is in two parts. The bottom half, which holds the action, is polymer, and the upper half, housing the steel cylinder and barrel, is aluminum. In 2010, Ruger announced a .357 magnum version of the LCR with a steel upper half that weighs a few ounces more.

Right now, Ruger offers 19 options in their LCR lineup, including six different calibers and the LCRx variants, which add a single action capability and some 3-inch models.

Before we get into comparing these two revolvers in detail, I just want to say up-front that I don’t have a dog in this fight. I have owned and carried multiple J-frames and LCRs. I like both of them for different reasons. I’m going to compare these guns one attribute at a time but it’s not my intention to ultimately declare one better than the other overall. That’s going to depend on which specific model you’re looking at and how you prioritize each of these attributes based on what your needs are.

1 – Size

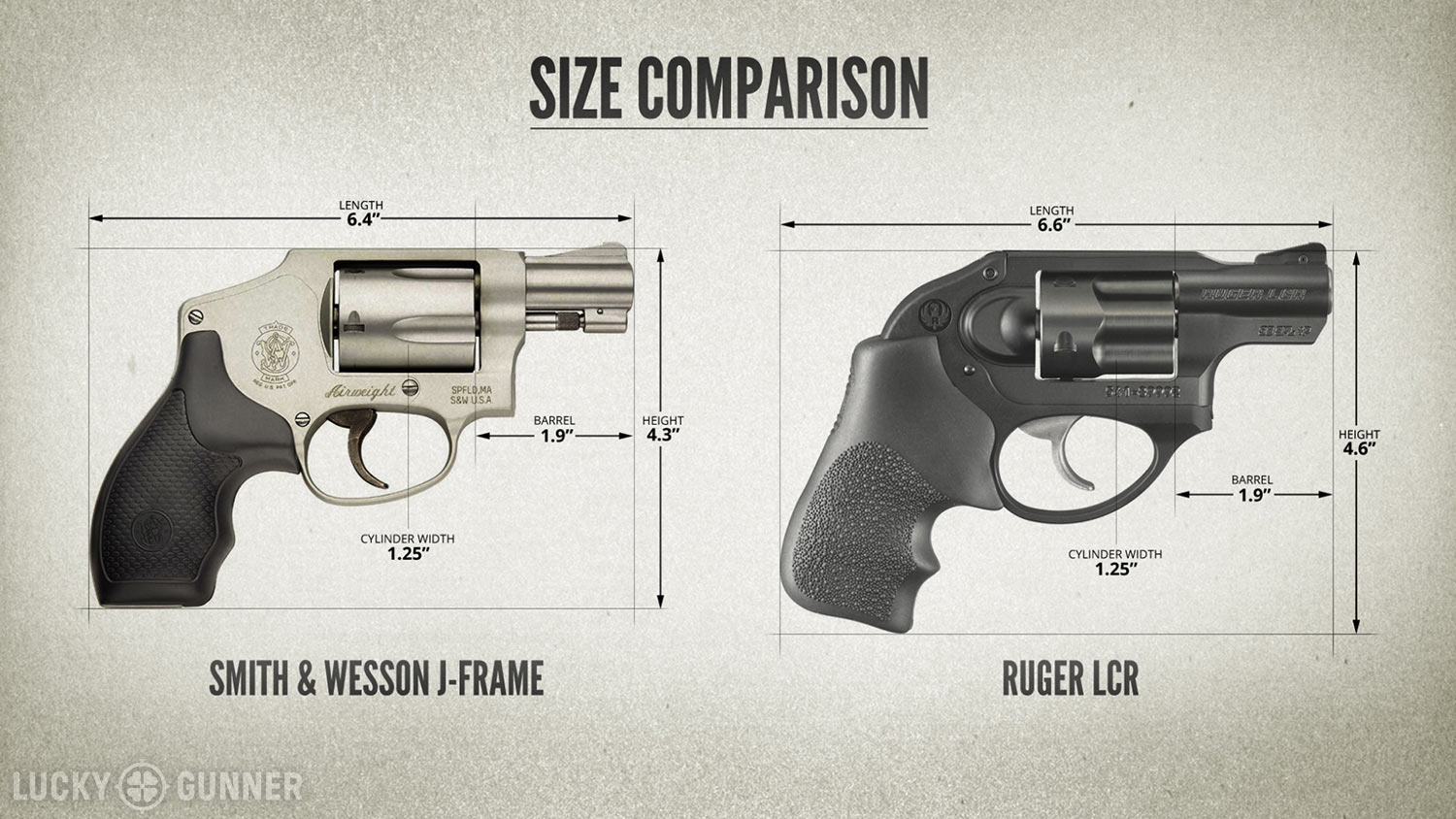

Let’s start with a look at the outer dimensions. The Ruger is slightly larger than the Smith. They have the same barrel length and cylinder width, but the LCR frame is about a quarter inch taller through middle and the stocks or grips tend to be about a quarter inch longer as well. That’s not much, but depending on how you’re carrying the gun, a quarter inch could be the difference between being completely concealed and a gun that prints enough to be noticable. So in terms of size, the Smith offers a very slight advantage.

2 – Caliber Options

Okay, so how about caliber options? J-frames have been offered in tons of different calibers over the years, but in the current Smith & Wesson catalog, there are only four options: .38 Special, .357 Magnum, .22 Long Rifle, and .22 Magnum. The LCR is available in all of those same calibers plus 9mm and .327 Federal Magnum. If you look hard enough and you’re willing to pay a premium, you can find some discontinued J-frames in those calibers, but they’re pretty rare. The LCR comes in more caliber options that are readily available today.

3 – Action/Trigger

Next, let’s talk about the action, or the quality of the trigger pull. J-frames have a notoriously stiff and heavy action. They can be a real challenge to master, especially on the lightweight guns. The LCR is known for having a smooth and reasonably light trigger, usually around 10 pounds.

So the Ruger would seem to be the obvious choice in this category, but I want to add a couple of caveats to that. First, the J-frame triggers tend to get significantly better with use. It might take a couple thousand dry fire repetitions, but eventually, the trigger will get smoother. If you want a short cut, there are some aftermarket spring kits that can make a huge difference too, but you do have to watch for light primer strikes if you start messing with the springs.

There’s also a minor downside to the LCR’s action. It has what you might call a “false reset.” When you fire the gun and you’re letting the trigger reset, there are a couple of “clicks” that kind of feel like the trigger is ready to go again, but it’s not. If you try to press the trigger again too early, the cylinder will turn, but the hammer won’t fall and the gun won’t fire. Some people never even notice this and it’s not a problem at all. It tends to be more of an issue for people who have shot J-frames a lot. The J-frame trigger has a slightly shorter length of travel. If that’s what you’re used to, it’s really easy to short stroke the trigger on the LCR, especially if you’re shooting fast. I wouldn’t call that a deal-breaker for the LCR, but it’s something to be aware of.

4 – Sights

Okay, now let’s look at which one has the better sights. The sights on our semi-auto pistols have improved drastically over the last 30 years or so, but unfortunately, that has not been the case for snub nose revolvers [For more on this topic, read “Snub Nose Sights: Do They Matter?”]. Most of the J-frames and the LCRs come standard with a shallow notch in the top strap for a rear sight and a ramp-style front sight. On most of the J-frames, it’s an integral fixed front sight that’s machined into the top of the barrel. Some of the J-frames and all of the LCRs have a pinned front sight, so at least you can swap it out for something else like a night sight or a fiber optic.

There are a few models with decent sights. The 3-inch J-frames and LCRs have adjustable rear sights that aren’t too bad. Some of the newer J-frames have a U-notch rear sight and an XS big dot front sight. The Smith & Wesson 640 Pro is an all-steel J-frame with dovetail cuts for the front and rear with semi-auto style night sights.

Even if you end up with a model that has lousy sights, you can always add some Crimson Trace lasergrips which are available for both the J-frame and the LCR. But for the LCR, they’ve discontinued the compact models like this and the one they’re still making is quite a bit larger. For the J-frames, there are four different styles available, including the compact grips.

So overall, the sights situation is not great but there are more decent options available with the J-frames.

5 – Weight

Judging these revolvers based on weight is a bit complicated because weight is not necessarily a bad thing. Lightweight revolvers are easier to carry but heavy revolvers are easier to shoot.

| J-FRAME VS LCR WEIGHT COMPARISON | |

| MODEL | WEIGHT (OZ) |

| S&W 350 PD [.357 mag] | 11.8 |

| Ruger LCR [.38 Spl] | 13.5 |

| S&W M&P 340 [.357 Mag] | 13.8 |

| S&W 642 [.38 Spl] | 14.4 |

| Ruger LCR [.357 Mag] | 17.1 |

| S&W 640 Pro | 22.4 |

Let’s take a look at a few different models sorted by weight. At the very bottom we have the all-steel J-frames like the 22.4-ounce Model 640 Pro I just mentioned. If you want a Ruger that is as pleasant to shoot as a steel J-frame, you have to move up to the larger SP101.

The heaviest LCRs are right around 17 ounces. They have a steel upper half, but the polymer lower keeps the weight manageable. I think the .357 LCR loaded with .38 Special offers a nice balance of being easy to carry and shoot.

Next, we’ve got the iconic S&W 642 Airweight with an aluminum frame and a steel cylinder coming in at 14.4 ounces. Guns this light are really convenient if you’re carrying in a pocket or on the ankle or really any method of carry that’s not on your belt. On the other hand, even with .38s, these guns are a handful. Airweight J-frames have the potential to be incredibly useful for the people who have put in the practice time to make good use of them. Smith & Wesson sells a lot of Airweights to people who don’t know any better and for inexperienced shooters, this is not a good choice.

If you’re a glutton for punishment and your J-frame just has to be a magnum, you could go for the M&P 340. The frame is aluminum blended with a metal called Scandium to make it lighter and stronger… and more expensive. And right around the same weight, we have the original .38 Special LCR at 13.5 ounces. Some people say the recoil is not quite as bad in these as the Smith & Wesson Airweights, but it’s still going to be pretty snappy.

Among the very lightest of the J-frames is the 340 PD. This one has a scandium alloy frame and a titanium alloy cylinder making it just 11.8 ounces. You can shoot magnums through these, but it’s something people tend to do only once.

This is a 342 PD, which is the .38 Special-only version of the 340 and it’s a full ounce lighter. It’s no longer in production, unfortunately. I really don’t enjoy shooting anything other than wadcutters out of this gun, but it’s really nice to carry. I forget I have it with me half the time — I think it weighs less than my wallet.

So while I would not say the LCRs are too light or too heavy — you definitely have a broader range of options with the J-frames.

6 – Durability/Reliability

Durability and reliability: the J-frame and the LCR typically exhibit both of these qualities. Of course, there are always exceptions. I have had to send a J-frame and an LCR back to their respective factories for repair after very little use. The J-frames have the advantage of a much longer track record. There are steel J-frames out there with decades of regular use that have been neglected and abused that still work just fine. On top of that, we’ve got books and manuals and tons of other resources out there all about how to maintain and troubleshoot a J-frame.

The LCR has been out almost a decade and it’s developed a pretty good reputation, but compared to the J-frame, it’s still relatively unproven. There aren’t many LCRs out there that have 10,000 rounds through them. It does seem to be a very solid design and I’m not aware of any common widespread reliability issues with the LCRs.

With both the LCR and the J-frames, if you’re going to have problems, they are most likely to show up either within the first couple hundred rounds or after several thousand rounds. If the gun runs fine with the first few boxes of ammo it will probably keep running as long as you keep it clean. When you get into very high round counts, especially with high pressure ammo, the aluminum frames guns can start having problems because of the harder steel parts causing wear on the softer aluminum over time.

While we’re on the subject of reliability, I should also mention the Smith & Wesson internal lock. This is a safety feature they started adding to their revolvers in the early 2000s. It is almost universally hated. The locks have been known to occasionally engage all by themselves under the force of recoil, which means the gun is completely locked up until the user can find their key and unlock it. This problem appears to be most common with the lightweight guns. Fortunately, in the last few years, Smith & Wesson has started to offer some of their J-frames without the internal lock, but only the double action only models. If you buy a new J-frame with an exposed hammer, it’s going to have an internal lock.

So in terms of overall reliability and durability, I don’t think I can choose J-frame in general over LCRs or vice versa. Let’s just call this one a tie.

7 – Aftermarket Support

Okay, we’ve got just two more categories to look at. Aftermarket support: the J-frame wins by a mile. You can find just about any holster you want for the J-frame. Speed loaders, spring kits, grips, you name it, you can find it for the J-frame. There is plenty of aftermarket support for the LCRs, but if you’re looking for something really specific, you’re a lot more likely to find a J-frame-compatible version of whatever it is.

8 – Cost

And finally: cost. Most LCRs are priced between $400 and $500 with the magnums at the higher end of that range. Maybe $50 more for the 9mm and .327 versions. J-frame prices are all over the place. At the low end, the standard 642 Airweight is usually around $350. But some of the ultra-lightweight models with the exotic metals sell for $800-900. The average price of a J-frame is probably higher than the average LCR price, but you can get a new J-frame cheaper than you can get a new LCR. So this one is also a tie.

Even though we’ve been looking at this as “J-frames versus the LCR,” I don’t think it’s fair to call one of them generally superior to the other. I think of the J-frames as being best if you want something really light or if you want a small steel frame gun that you can shoot a lot. The LCRs are better if a smooth trigger is a priority or if you’re looking some of the more obscure revolver calibers. Either way, when you decide on a snub nose revolver, make sure you feed it with ammo you can get with lighting fast shipping from us at LuckyGunner.com.

Want more detailed info on these revolvers? Be sure to check out our Guide to Smith & Wesson .38 Special and .357 Magnum Revolvers. We’ve also got a review of the 9mm Ruger LCR in the archives, and another one on the .22 LR Ruger LCR.