Today, we’re exploring the differences between short barreled rifles (SBRs), pistols, and pistols with stabilizing braces. What are the legal differences and why? What are the advantages of owning one over another? And why don’t you ever see me using a braced pistol in our videos?

Watch the video below for all the details, or scroll down to read the full transcript.

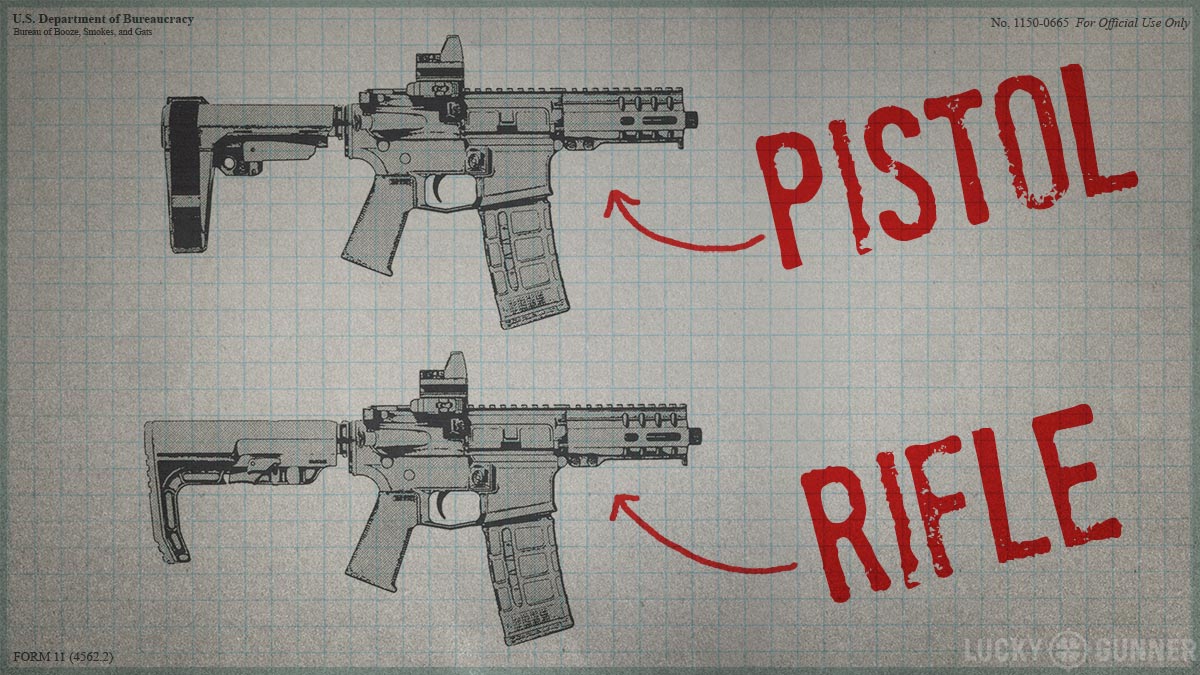

Hey everybody, I am Chris Baker from LuckyGunner.com. Today, I want to talk about how and why we got to a place where the Federal government considers this to be a pistol and this to be a rifle, despite the fact that they look nearly identical.

I’m also going to get into the benefits of owning a registered short barreled rifle versus a large format pistol. There are pros and cons to each, both legally and practically speaking.

What Do We Call These Things?

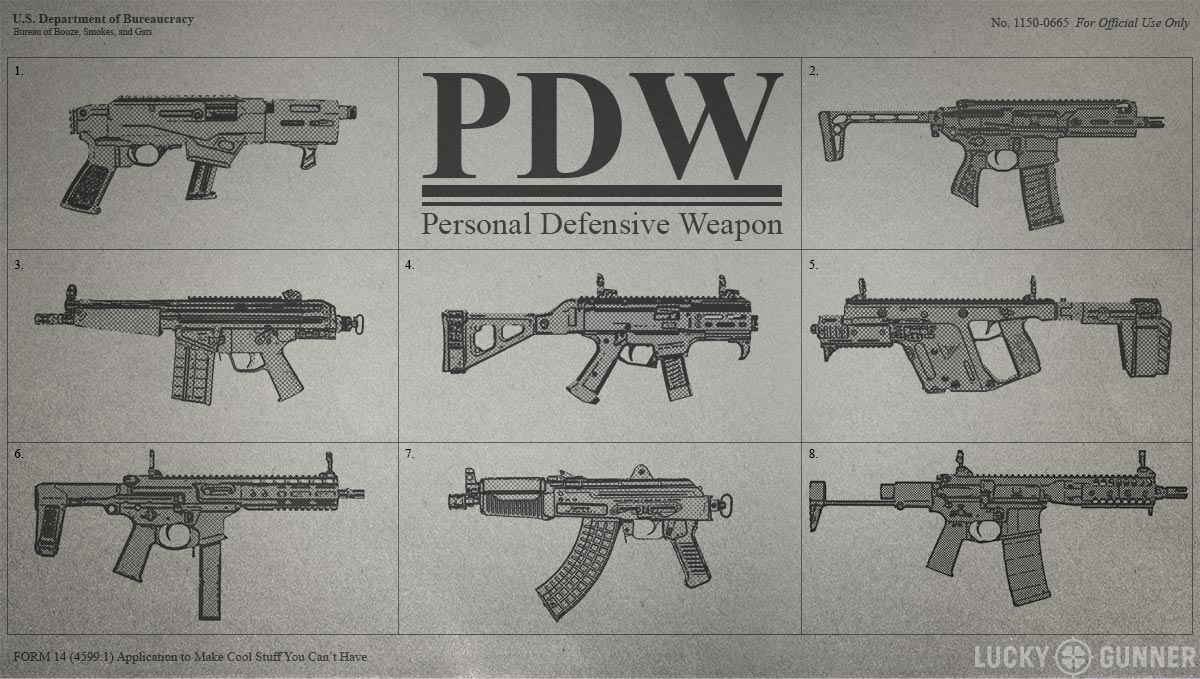

For the sake of simplicity, I’m going to refer to this broad category of firearms as PDWs, which is short for Personal Defensive Weapons. I know that traditionally, PDWs are technically selective-fire, but obviously we’re looking at their semi-auto counterparts here. Basically, we’re talking about firearms that are somewhere between what we typically think of as a pistol and what we typically think of as a carbine.

My demo gun today is a CMMG Banshee 9mm upper with a 5-inch barrel on an Aero Precision lower receiver in a pistol configuration. It feeds from P-mags with a 9mm conversion kit. I’ve got some other stuff planned for this gun if you guys want to hear more about it in the future.

Obligatory Disclaimers

A couple of disclaimers before we get into it: I’m going to be talking a lot about firearms law and interpretation of that law. I am not a lawyer or a legal expert of any kind. “Lucky Gunner” is the name of our online ammo store, it’s not the name of a good legal strategy. You really shouldn’t listen to me. If you follow my suggestions and you get arrested, that’s your own fault.

Also, everything in this video is current, as far as I know, as of mid-July 2020. But this stuff can change at any time. If you’re watching this a couple of years, or even a couple of months down the road, there is a good chance that at least some of what I’m about to say no longer applies.

And you should be aware that my focus here is federal law. Some states have laws regarding short barreled firearms that are more restrictive than federal laws, so do your homework there.

One last thing before we get into it — I’m not bringing this topic up as a way to promote any political agenda. It’s not that that stuff is irrelevant or that I don’t have an opinion, it’s just beyond the scope of our discussion today. My goal here is to simply explain the reality of the legal situation and what options you have as far as the hardware you can own. If you don’t like that legal situation, I encourage you to take some proactive steps to change it. Write a letter, start a protest, join an organization. But please, no one in the comments section wants to read your political manifesto. Do that somewhere else.

History of SBR Laws And Non-Pistol Pistols

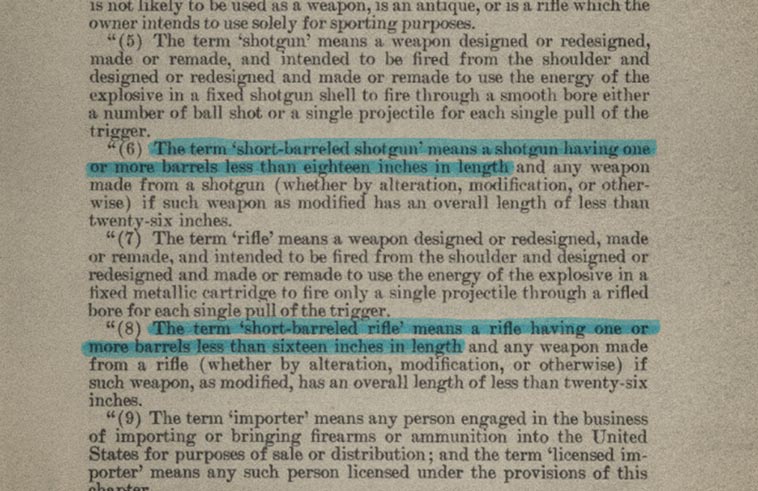

Okay, back to the topic at hand. And let’s start with a little history lesson. We have to go back to 1934 with the passage of the National Firearms Act. It covers a lot of territory and it’s been amended a few times over the years. For now, the part we’re concerned with is minimum barrel lengths. According to the NFA, rifles must have a barrel length of at least 16 inches. For shotguns, it’s 18 inches. Anything shorter is considered a short barreled rifle or shotgun. You can own an SBR or SBS as they’re commonly known, but you first have to pay the ATF a $200 tax for each one. You also have to submit some paperwork with that $200. These days, it can take over a year for the ATF to process and approve your application.

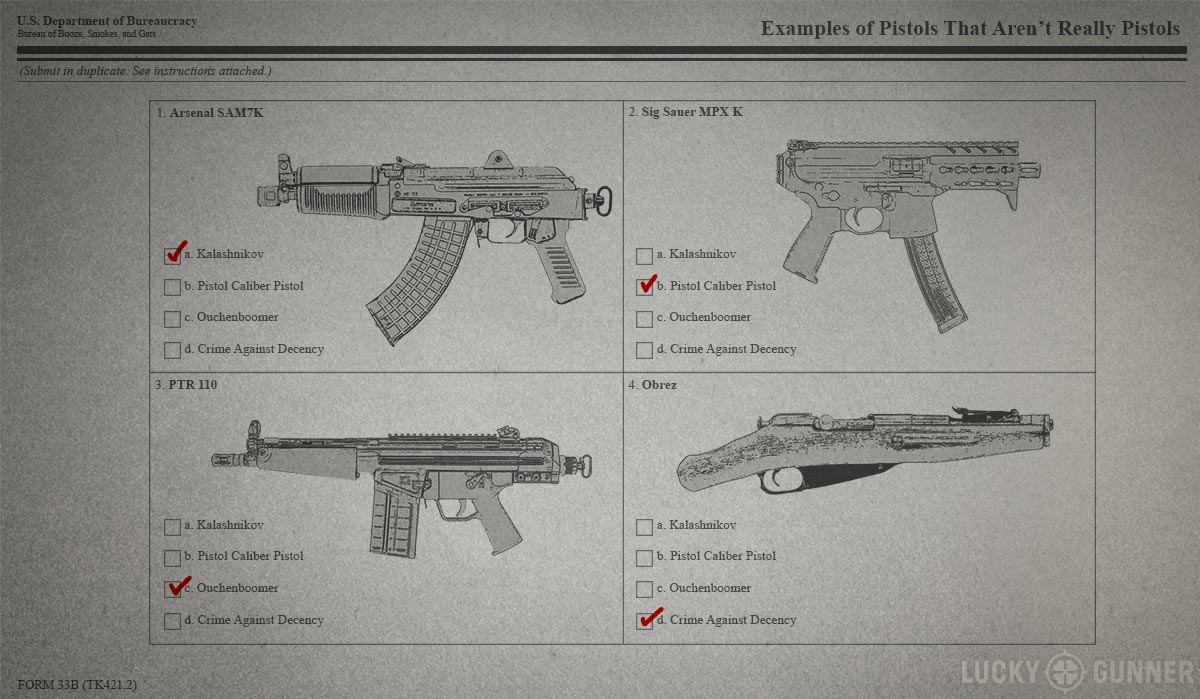

Now, let’s fast forward to about a decade ago. The black rifle market was booming and the gun companies were running out of ideas for AR variants. We started seeing something on the market that had previously been somewhat uncommon and that was AR-style pistols. These were essentially AR-15s with no shoulder stock. Without a stock, legally speaking, it’s not a rifle, it’s a pistol. Because it’s a pistol, there’s no restriction on minimum barrel length. So you can have an AR with a barrel under 16 inches and it’s completely legal — no extra NFA paperwork required. It’s a pistol.

And it wasn’t just ARs that got the pistol treatment. There were pistol style AKs, and pistol versions of pistol caliber carbines, and all kinds of other guns.

The ARs are kind of unique, though, because they still have a buffer tube or receiver extension. This tube isn’t just something to attach a stock to. It’s a necessary part of the gun. There’s a spring and a buffer in here and the gun has to have them to function.

At first, I think most of us who would consider ourselves “serious shooters” thought of these large format pistols as nothing more than a novelty and a fad. They’re too big to shoot like a traditional pistol. And without a stock, you can’t really run them like a rifle — you lose those third and fourth points of contact that make a rifle a rifle. But a lot of people were buying them and having fun with them, and that’s fine. There’s nothing wrong with a good range toy if that’s your thing.

Enter: The Stabilizing Pistol Brace

Fast forward again a couple of years to the 2013 introduction of the stabilizing pistol brace. SB Tactical was the first company to develop one of these. It is essentially a device that’s designed to allow the shooter to brace a PDW-style pistol against their forearm so they can shoot it one handed. The inventor actually came up with the idea so his disabled friend could more easily shoot an AR pistol one-handed.

Since then, several other pistol brace designs have come out. Some of them have loops and velcro straps, some of them don’t. The ATF signed off on this. They have individually approved several of these devices and said yes, you can attach a brace to your pistol and it’s still a pistol, it’s not a short barreled rifle. With an AR, you can stick it on the buffer tube. Other types of PDWs use folding extensions and other add-ons to attach the brace to the receiver.

So that is how we ended up with pistols that look just like short barreled rifles but they’re regulated completely differently.

Legal Confusion

Now, here’s where things get messy. It doesn’t take a whole lot of imagination to look at one of these and consider that, you know, in a pinch, one could rest that brace against one’s shoulder and it might work a whole lot like a rifle stock. And that’s exactly what some people did. Other pistol brace owners were a little more reluctant. So the ATF started getting a lot of questions about the legality of using a pistol brace like a shoulder stock.

ATF’s 2015 Open Letter

After several ambiguous and conflicting statements from various ATF personnel, in 2015, the ATF wrote an open letter. That letter points out that the NFA definitions of both rifle and shotgun include the phrase any “weapon designed or redesigned… and intended to be fired from the shoulder.”

Since the NFA doesn’t elaborate on what the word “redesign” means, the ATF had their own interpretation. They took it to mean that anyone who shoulders a pistol with a brace has “redesigned” the gun to be an unregistered, short barreled rifle. Which is a felony.

So sales of pistol braces dropped dramatically. Shooters were reluctant to own something that could make them a felon if they just happened to hold it incorrectly when the wrong person just happened to be looking.

A lot of legal experts called foul, including SB Tactical’s attorneys. Their basic reasoning was that someone using a pistol brace in a way other than it was intended should not change the legal classification of the hardware itself. Using something incorrectly is not the same as redesigning it.

The 2017 “Clarification”

In 2017, ATF issued a response. But what’s interesting is that they didn’t write another open letter to clarify their 2015 letter. It was a private letter addressed only to SB Tactical’s legal team. Fortunately, SB Tactical made that letter public. The ATF’s clarification was that “incidental, sporadic, or situational ‘use’ of an arm-brace (in its original approved configuration)… at or near the shoulder” does not constitute a ‘redesign.’”

They also say it would be considered redesigning the gun if you physically altered the arm brace in any way to make it easier to use as a rifle stock. The examples they give are removing the arm strap or permanently attaching the arm brace to the buffer tube.

So Can You Shoulder a Pistol Brace or Not?

Some people have taken this 2017 letter to mean that you can do whatever you want with a pistol brace as long as you don’t make any modifications to it. But it’s not that simple. One thing the ATF has been consistent about is that if you buy a pistol brace with the intention of using it as a shoulder stock, you’re in violation of the law. Since they can’t read people’s minds to know their intent, the ATF is looking for indicators of intent. The legal term for that is “manifest intent.” Your behavior indicates your intent. Modifying a brace with the examples they gave is just one indicator.

The “Secret Rules”

Unfortunately, the ATF has not been forthcoming about what other indicators they’re considering. We’re basically back to where we were before 2015. Again, individuals and companies are getting arbitrary and sometimes contradictory advice from various ATF personnel. Some sources have said that the ATF expects your brace-equipped pistol to have a length of pull under 13.5 inches. Some have said the ATF frowns on braced pistols with magnified optics unless it’s a forward-mounted long eye-relief optic. There are rumors that they don’t like braces on pistols weighing less than 40 ounces. So, something like a Glock with a brace attached to a stock adapter.

None of these supposed rules have been made public and there’s no way to know when the ATF has come up with a new one. Considering the stiff penalties involved if someone were convicted of violating NFA laws and the fact that there are something like three million pistol braces out there in the wild, this legal ambiguity is a pretty big problem. It’s a big enough problem to show up on the radar of a few US Congressmen. Last month, seven of them signed a letter to the ATF asking them to quit messing around and tell us the actual rules for determining what’s a pistol and what’s a short-barreled rifle. Hopefully we’ll hear something approaching a final answer in the near future.

Again, I’m not bringing this up to make any kind of political statement. But if you want to own a PDW, you should know that the rules are not always clear.

So until that situation is resolved, let’s take a look at what our options are. If you’re interested in owning a PDW-style firearm, there are a few different ways you can go about it.

Option 1: Be a Scofflaw

First, you can just ignore all of the laws completely. It’s pretty easy to do. You just get a pistol and put an actual rifle stock on it. Don’t pay the tax. Don’t register it. Have fun! But… don’t do that.

I know it seems like it would be just “barely a crime,” kind of like speeding or something. But the ATF takes it pretty seriously. If you’re convicted of violating the NFA, you could face jail time of up to 10 years and fines up to $250,000 for each offense. And you would be prohibited from owning any firearms for the rest of your life. So, probably not a good option.

Option 2: Registered Short Barreled Rifle

Second, you can go with a legal, registered short-barreled rifle. You can buy one or build one. Either way, it will cost you $200 for the NFA tax stamp.

Buy it with a Form 4

If you buy an SBR outright, that’s going to be an ATF Form 4. It usually takes at least a few months to get one of those processed. After it’s approved, you can pick up the gun from your FFL dealer.

Build it with a Form 1

If you build one, that’s an ATF Form 1. Lately, they’ve been approving those much quicker, sometimes in just three or four weeks. Building an SBR really can just mean that you buy a pistol and then once your stamp comes back, you put a stock on the gun. That’s considered “making” an SBR. There are more details you should know before you go the NFA route. Fortunately, we’ve got access to a ton of great resources online for filling out that paperwork to make sure it gets processed as quickly as possible.

Just as a quick aside, I haven’t had many nice things say about the ATF. But I do want to acknowledge that there are a lot of good, hard working people employed by the ATF. Especially on the admin side of things. Some of them are even shooting enthusiasts just like you and me. So if you have to talk to someone at the ATF about your paperwork for whatever reason, just keep in mind that they are not the one responsible for the dysfunctional rules and regulations.

Advantages

Once your Form 1 or 4 gets approved, there are very few downsides to owning an SBR. You can have whatever barrel length or stock you want and you can change it whenever you want.

Just like any other firearm, it’s only the receiver that legally counts as the SBR. The rest of the gun can be configured and reconfigured at will. So, for example, if you have an AR with an SBR lower receiver, you can own multiple uppers to swap around and use with that lower.

Disadvantages

There are some drawbacks to taking the SBR route. You are registering the gun with the federal government and you’re in the ATF’s database. That, understandably, doesn’t sit too well with a lot of people.

In some states, it’s illegal to have a loaded rifle in your vehicle but you can have a loaded pistol. So if you’ve got the gun in your go-bag or whatever, a registered SBR would have to be totally unloaded in those states — no mag, no round in the chamber.

For a lot of people, the main disadvantage of an SBR is the interstate travel restriction. Even if your SBR is registered and completely legal, you can’t take it across state lines without notifying the ATF first. There’s a form you have to fill out and wait for the ATF to approve it. It usually only takes a few weeks to get back, but it’s still a hassle. One of the great things about an SBR is that it’s easy to pack up and take with you. But that is somewhat negated by the interstate travel rule.

Option 3: Pistol with a Stabilizing Brace

Your third option for owning a PDW is to get a pistol with a stabilizing brace.

Advantages

With a pistol, you don’t have to deal with any of the disadvantages of an SBR. No registration or notification requirement for interstate travel. No $200 tax.

Disdvantages

The downsides: you have to be really careful about how that gun is configured so that it legally stays a pistol. There are certain things you can do to a rifle that you can’t do to a pistol. At least, not without violating the NFA. For example, you cannot put a vertical foregrip on a pistol. And the definition of a vertical foregrip is another one of those things the ATF has not been consistent about. Does an angled foregrip count as a vertical foregrip? Maybe, maybe not.

Personally, I’ve never had much use for vertical foregrips, angled or otherwise, so I don’t consider that to be much of a disadvantage. But there are other issues with the braced pistol PDWs.

Stabilizing pistol braces are not exactly cheap. The most popular models have an MSRP around $150-200. There are some inexpensive pistol braces, but they tend to be not quite as comfortable to use and you might have to make some modifications to your gun to get them to fit. So a pistol with a brace is not necessarily going to save you a whole lot of money versus paying for a $200 tax stamp.

The biggest disadvantage to a braced pistol is what I already talked about. They’re kind of in a legal gray area that could change at any minute. You’re not supposed to buy a pistol brace solely as a means of avoiding the SBR laws. The ATF is really unlikely to change their stance on that part of the issue.

What could and probably will change are the criteria the ATF is using to determine what is and isn’t a pistol brace and how a brace can be used. Or they could resort to the nuclear option and just outlaw pistol braces completely. The ATF doesn’t need any new legislation or a judge to be able to do that. They can just write some letters and boom: get rid of your pistol brace or you’re committing a felony.

For the time being, pistol braces are totally legal to own as long as you use them as intended. They may or may not be legal if you sometimes use them as they were not intended. Until there is more clarification on that, you probably won’t see me shoulder a pistol brace on camera. And I’m not suggesting you do it either.

Option 4: Pistol without a Brace

I do want to suggest one more alternative for a PDW. You could simply go with a large format pistol without the brace.

Advantages

The benefits of going this route are that you don’t have to deal with the legal ambiguity. As far as I know, the ATF has not even hinted that they might want to reclassify AR pistols as SBRs when there is no brace involved. If you really want to go the extra mile, you can install a plain pistol buffer tube on your AR if it doesn’t already have one. It’s probably not necessary, but it does make your AR pistol a little more “pistol-like” since there aren’t many stocks you can attach to one of these tubes.

At the beginning, I mentioned that a lot of people, myself included, originally considered these AR pistols to be novelties and range toys. I’ve been rethinking that opinion recently and a lot of credit for that goes to Rhett Neumayer. Most of you guys probably don’t know Rhett. But he’s become one of my favorite outside-the-box thinkers in the shooting world.

He and I have had some conversations about a technique he’s come up with for effectively running stockless shotguns like the Mossberg Shockwave. More recently, he’s taken some of those same principles and modified them to get some pretty impressive performance out of an AR pistol without a brace. You can see more on his YouTube channel at Demonstrated Concepts LLC.

Basically, it’s a combination of stabilizing the gun with tension from a two-point sling and getting a firm cheek weld on the buffer tube. Rhett can run his 10.5-inch 5.56 AR pistol that way almost as well as he can with a shoulder stock. I’ve tried it with this gun and it hasn’t been quite that effective for me. But this little 5-inch gun has more upward muzzle movement and there’s a lot less space on the forend to get a good grip. An 8-inch or longer barrel would probably be a little easier to control. Still, it’s the most viable technique I’ve seen for running an AR pistol without a brace or a stock on it.

Disadvantages

Couple of downsides — this technique is dependent on having both a sling and a buffer tube or some other kind of receiver extension. That means it may not work nearly as well with non-AR pistols. It’s also not going to work as well if you’re in a situation where you don’t have time to put on your sling. I’ve tried it with just the cheek weld and I’ve tried it with just the sling, and I wasn’t super impressed with the results either way. They were both much slower than using the combination of both sling and cheek weld.

I’ve also tried the old school single-point sling method. That technique relies on a similar principle where you extend the gun out to get tension on the sling as a way to stabilize a stockless gun. I believe it was first developed around compact stockless submachine guns like the MP5K.

It actually worked a little better than I was expecting. It wasn’t bad as a means of mitigating recoil. But it was really difficult to get the sight to track in any kind of predictable pattern. That’s where the cheek weld on the buffer tube is really helpful. It keeps your eye in a consistent position relative to the sights. But if your gun doesn’t have a buffer tube, I think the single point sling technique is worth trying.

I hope at least some of that was helpful for you guys. If you think you learned something, do me a favor and leave a nice comment and subscribe to our email newsletter if you haven’t done that already.