All handguns recoil. It’s a perfect demonstration of Newton’s Third Law. But the way we experience that recoil — the perceived or felt recoil — often varies dramatically from one gun to the next. Even if we compare two guns of equal weight firing the same cartridge and theoretically transferring the same amount of energy to the shooter’s hand via recoil, it’s possible for the felt recoil to be vastly different. We analyzed some more high speed footage to help explain why.

Details are in the video below, or scroll down to read the full transcript (although this time, it won’t make a whole lot of sense without watching the video).

Hey everybody, Chris Baker here from LuckyGunner.com. Today, we’re going to look at more high speed footage to better understand what happens during handgun recoil that we normally cannot see with the naked eye. This time, we’re looking for clues that might help explain why recoil feels different from one gun to the next.

I don’t just mean that some guns recoil more or less than others, although that’s part of it. Why do we describe recoil as snappy or soft, bouncy or smooth, harsh or flat? We’re not just talking about the magnitude of the felt recoil. And it’s more than the subjective differences based on factors like technique, hand size, and grip strength.

Every handgun recoils a little differently than others. We’re going to look at some comparisons where that difference is really obvious.

Revolver vs. Semi-Auto Felt Recoil

The most overt example is revolvers versus semi-autos. Here, we’ve got a Wilson 9mm 1911 and a Ruger GP100. They weigh about the same. They’re different calibers, but both are firing the same bullet weight at comparable velocities.

When you fire a revolver, all of the recoil energy is immediately transferred to your hand. With the 1911, there’s a short delay and the recoil is spread out over a longer period of time. The bore line of the revolver is also much higher relative to the hand and wrist. All of these factors combine to make the revolver feel like it has significantly more recoil even when the total amount of energy delivered to the shooter is roughly the same.

But there are other differences. For example, the revolver’s muzzle arcs up when it’s fired and immediately back down because of the pressure I’m exerting on the grip. The 1911 arcs up, and then there’s a moment when it seems to kind of stall. It’s moving back down, but very slowly at first. Then the slide closes and that has kind of a reverse recoil effect. It helps to push the muzzle back down on target.

If I speed it up some and let it play out, you can see another side effect of the slide movement. The force of the slide closing causes the muzzle end of the pistol to bounce up and down a few times. The revolver muzzle just snaps back on target and stays there.

I can still see the front sight on that 1911 while it’s bouncing around. If I’m just trying to throw rounds into the center of a big cardboard silhouette, I don’t have to wait for that sight to completely settle before I fire another shot. But it’s not ideal, and I much prefer the way the sights track on the revolver, even though it takes more effort to control the recoil.

Again, there is some subjectivity here. If you shot these two guns, you’d probably notice some differences but they might not be the same ones I just mentioned. Except that the revolver has more felt recoil – that’s pretty universal.

Small-Frame Revolver vs. Pocket Pistol

Let’s look at another revolver-semi-auto pair. This time, a Ruger LCR and a Glock 43, both in 9mm firing Speer Gold Dot 124 gr +P.

These are much lighter guns, so the felt recoil is more severe. Again, more so with the revolver. The LCR has a decent-sized grip compared to the Glock, but even so, you can tell it really wants to free itself from my hands. It’s quite a handful with +P ammo.

This time, the revolver is the one that seems to stall at the top of the recoil arc. The short slide on this Glock takes less time to cycle than the big heavy 1911 slide. So that little assist from the slide closing happens sooner.

Both of these guns have a little bit of that muzzle bounce at the end. They also don’t return quite to the same spot they started – you can see that the muzzles are not level – probably because the grips have shifted slightly in my hands. I would have to deliberately re-align the sights before my next shot rather than letting my grip do all the work subconsciously.

I haven’t fired either of these guns in a long time. And as you can see, they’re very unforgiving. If you don’t grip a lightweight 9mm just right, the recoil is difficult to manage. Even tiny shifts in how the gun sits in your hand will often lead to erratic shot placement on target.

.380 ACP Blowback vs. Locked-Breech Felt Recoil

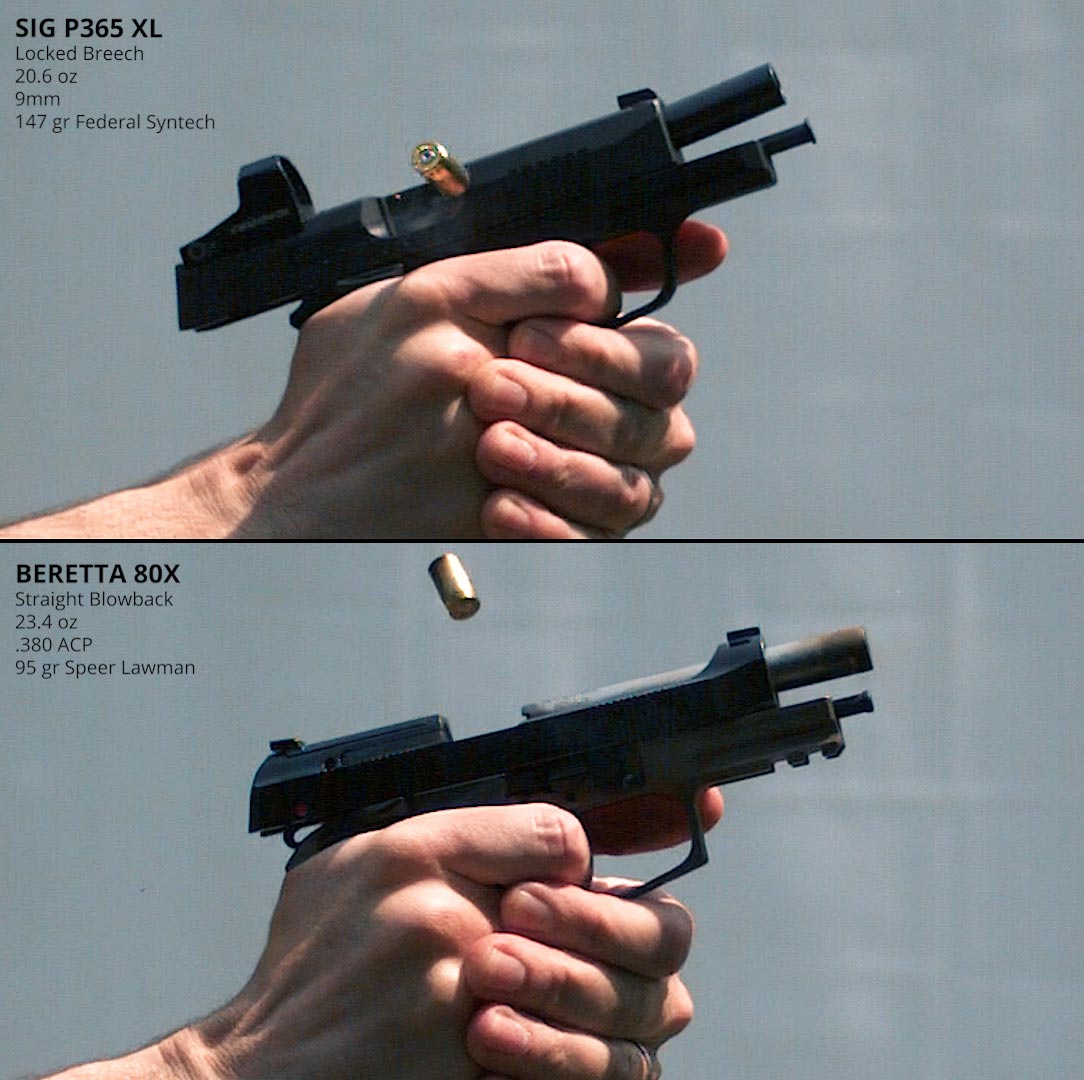

Let’s look at a different kind of comparison: blowback versus recoil operated pistols. Last time, I mentioned that I’m working on a review of this gun – the new Beretta 80X Cheetah. It’s an all-metal double stack chambered for .380 ACP. The recoil is not at all difficult to manage, but it’s also not insignificant. A lot of people use the word “snappy” to describe how this gun shoots.

That’s in stark contrast to something like the .380 version of the Sig P365. It’s a bit smaller and lighter than the Beretta, but the perceived recoil is very mild by any standard. That’s because the Sig is a recoil-operated or locked-breech pistol while the Beretta 80X is a straight blowback design.

A while back, I did a video on the difference between these pistol types in case you want the detailed explanation. For our purposes today, all you really need to know is that blowback pistols have a stationary barrel – only the slide moves. With a locked breech pistol, the barrel does move. It’s locked to the slide and they move together for the first couple of millimeters of travel, and then they unlock and separate.

You might have heard before that blowback pistols feel like they recoil more than locked breech pistols of the same size, weight, and caliber. But why is that, exactly?

I’m going to put the two side by side, but for now, focus on the Beretta. Let’s pause right there. At this point, the Beretta’s slide is completely open. So far, the frame and my hands are in exactly the same position they were at the beginning. Then that recoil force travels from the slide to the frame all at once and you can see my hand react.

I’ll play that again, but watch the Sig this time. We’re paused here at the same point. The Beretta slide is completely open but the Sig’s slide is not there yet. It takes a little longer, probably because the barrel was locked to it at the beginning. They’re not together for long, but it would be like if you had a ten year old riding piggyback for the first five feet of a hundred meter sprint – that’s gonna slow you down. We also can already see some muzzle rise at this point. The gun is not level anymore. If we go frame by frame, you can see movement begin in the pistol frame and my hand just after the barrel unlocks.

Since the slide is moving slower, it opens with less force than the Beretta slide. That results in less muzzle rise. Watch it one more time and pay attention to the back of my hand on the Beretta when the slide opens. That little ripple in the skin is probably what we’re feeling when we say a gun like this is “snappy.”

So we have two pistols firing the same cartridge. You’d expect to feel more of the recoil with the Sig because it’s a few ounces lighter. But because it’s a locked-breech design, that recoil is spread out over a longer period of time, which we perceive as less recoil. This principle has limits. For example, the Beretta 80X is far easier to manage than a locked-breech pocket pistol like the Ruger LCP. Not only is the LCP much lighter than the P365, the grip has very little surface area, which concentrates the recoil force and is not much fun to shoot.

.380 ACP Blowback vs. 9mm Locked-Breech

How about if we compare the Beretta to a locked-breech 9mm of similar size and weight? Something like this 9mm Sig P365 XL. That’s the gun I was reminded of after my first range session with the Beretta 80X. But then I shot them side by side, and they felt very different. The Beretta has a snap while the Sig has more of a push, which is what you might expect. But it also seemed like the Beretta’s sights returned to the target a little quicker than the Sig’s. It’s similar to what we saw with the GP100.

The 9mm Sig recoils like the .380 version, there’s just more of it. The impulse moves to the frame and the shooter earlier than with the blowback gun. But now watch the slides close. From fully open to fully closed, the Sig’s slide takes 33% longer than the Beretta’s. Like the 1911, The Sig slide appears to linger in the open position. That has an impact on my ability to recover from recoil. And then when the slide finally does close, the muzzle starts to come down, but also causes the frame to jerk forward in my hands a little, which I have noticed when I’m shooting.

In the meantime, the Beretta muzzle is already on its way back down from grip pressure alone, even before the slide is completely closed.

Does Any of This Matter?

Now, if we watch these guns in real time, this all seems pretty academic. And it is, depending what you want to do with the gun. With a halfway decent grip, they both seem to snap back onto target pretty much instantly. Any proficient handgun shooter should be able to manage the recoil in either of these guns well enough for practical purposes.

But if you go through ammo by the case instead of the box or if you’re chasing some high performance shooting goals, these little quirks in the perceived recoil do make a difference. Either consciously or subconsciously, we learn how to compensate for the unique recoil characteristics of each gun when we spend a lot of range time with it. If we then try to shoot a different gun, it might take a while to kind of recalibrate our technique. Of course, recoil is not the only factor. But if all handguns had zero recoil, switching from one to another would be relatively trivial.

Like I said last time, watching these clips may or may not have any practical value for you. But if nothing else, shooting is fun and so are high speed cameras. Hope you guys enjoyed it. If so, be sure to subscribe to our channel and the next time you need ammo, get it from us with lightning fast shipping at LuckyGunner.com.