Last week I talked about why you should be dry practicing. This week I am going to talk about how to make the most of your dry practice sessions. Chris has talked about how to practice shooting here before. As with live practice, dry practice can benefit immensely from a training plan. Before we get into thinking about your dry practice session, we need to cover safety.

Dry Practice Safety

I’ll be honest, I have been dry practicing for many years, and it still terrifies me. It scares me because I don’t usually dry practice in a place that would be ideal for live fire. This means that if a round goes off, there will be some consequences. By taking good safety measures, I ensure that if I do negligently discharge a round, the most severe consequence will be some minor property damage. The moment you fail to respect dry practice as much as you would live fire, accidents happen. Here is my safety routine:

Designate a location

This is a bullet-safe location so that if a round is fired, it isn’t going any further than the backstop. And just to be clear, sheetrock, insulation, and OSB do not count as bullet-safe unless the terrain behind them will stop a bullet and there can be no chance a human will be in the space between. If that’s all you have, consider investing in a ballistic panel; I spend a good deal of time in hotels, and this is what I use.

Don’t dry practice anywhere else

I only dry practice in my designated location, and I don’t dry practice around the house. Though I sometimes see recommendations to dry practice at the television, I think this is bad business. Here’s why: most of the time, when I am in my house with a gun in the holster, the gun is loaded. A millisecond of mental lapse is all it would take to send a round through my television, the kettle on the stove, the wall, and from there…who knows? Pick a safe location and use it.

Separate firearm and ammunition

Ammunition never enters my dry practice area. Never. I unload the gun before I go into my practice area. Don’t forget your magazines, and it’s not a bad idea to check your pouches for a loose round. The only negligent discharge I have ever witnessed during a dry practice session was because the shooter had a loaded magazine in his gear.

Have a definitive beginning and end

Too many dry practice sessions have ended with a negligent discharge because the shooter wanted to do “just one more rep”. Dry practice sessions should have a clearly defined beginning and end. When the session is over, it’s over. No ifs, ands, or buts.

With safety appropriately covered, we can now talk about the practice itself.

Dry Practice with a Purpose

Contrary to popular opinion, dry practice isn’t just about developing trigger control. You will notice I consistently refer to it as dry practice and not dry fire. This is because dry practice and dry fire aren’t necessarily the same things. Dry practice can be about clearing concealment and drawing the gun. It can be about speed reloads. It can be about malfunction drills. It can be about maintaining sight alignment and sight picture while moving forward, backward, laterally, or while changing position. I also find dry practice absolutely crucial to practicing any sort of low-light skill. I haven’t found too many indoor ranges that would turn off the lights for me or outdoor ranges that are open after dark.

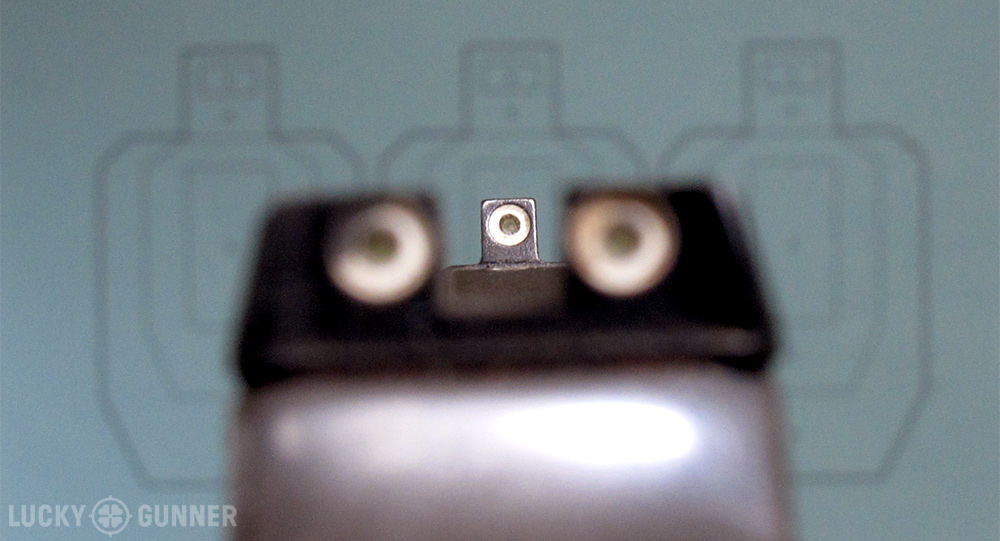

There isn’t much you can’t do dry, with a couple notable exceptions. The first is recoil management. The only way you are going to experience firing multiple rounds in succession is to get on the range and fire multiple rounds in succession. Another potential shortcoming of dry practice depends on the gun you are practicing with: trigger reset. If you shoot double-action revolvers like I do, or DAO semi-autos, this is a non-issue. If you are in the vast majority of concealed carriers who have chosen a striker-fired pistol, traditional DA, or single action only, this issue is a bit more complicated.

Prioritize, Prioritize, Prioritize

When deciding what to dry practice, you should prioritize your session based on two factors: the likelihood of use, and the potential for degradation. Assuming you are practicing for self-defense, you should address likelihood by asking yourself, “In the event I have to defend myself with my handgun, which skills will I absolutely use?” First, you will have to draw and present the gun, so the likelihood of using this skill is 100%. This means that you should dry practice drawing and presenting the handgun during every single dry practice session.

You should address degradation by assessing the skills that are likely to degrade through lack of maintenance and stress. Trigger control is a fine motor skill that is prone to degradation under stress, and if you’ve drawn your gun, there is a good likelihood you will need that skill. This combination of likelihood and degradation potential means that trigger control should be practiced every single time. Other skills, like malfunction drills, may need to be practiced far less often. The type I malfunction clearance (the old “tap, rack, reassess” drill) is composed of gross motor movements that are not terribly prone to degradation, and the technique itself has a low likelihood of occurrence. Because of this, you can probably get by practicing this only once a week or so. This doesn’t mean you never need to work it, but you probably shouldn’t spend time on it at the expense of other, higher likelihood skills or those that are prone to degradation.

The specifics of your chosen carry rig may make certain things a higher priority. Though the likelihood of a reload being necessary during a defensive encounter is incredibly low, it’s a little higher for me. This is because my carry gun only holds five rounds. Reloading a revolver is also a complex skill with a high likelihood of degradation. I am more likely to need the skill than someone with a double-digit capacity auto-loader, so I maintain it each and every time I dry practice.

Take Baby Steps

If you need to work on a specific skill, you can break your dry practice down into small, discrete steps. Let’s say you want to improve your emergency reloads. You can break the reload down into very small pieces – separation of the hands and moving the gun in your workspace, indexing the fresh magazine and removing it from the magazine pouch, inserting it into the magazine well and sending it home, releasing the slide (through the technique of your choice) and reacquiring a firing grip.

If you consistently find one element of the entire process needs work, focus on it alone. For example, if your post-reload firing grip is a bit off, you can work on this much more efficiently by focusing on it individually instead of the reload as whole: begin with the slide locked to the rear. Release the slide, reacquire your grip, and press the gun out to full extension. Lock the slide to the rear and repeat. You can do more repetitions of this motion, where the work is needed most than you can by going through the entire reload process, picking up dropped magazines, and resetting. This also keeps your attention sharply focused specifically on problem areas.

Measure your progress. The most objective way to measure it is by time. You can use a shot timer for this. A timer will give you a rock-solid, objective time to meet (or beat). If you don’t want to invest in a shot timer, set your iPhone up and record your draws, reloads, and other points of performance. Save these and compare them against the next session. Video is another good way to measure your progress. It is also a great way to identify inefficiencies in your technique and let you know what you need to focus on. Regardless of what measure you use, you should have a quantifiable standard through which you track your progress. Also realize that you will probably make huge gains initially, and, as you get better, these gains will become smaller and smaller.

Don’t overdo it. A high-quality dry practice session requires some mental and physical energy, and you should only practice as long as you can maintain good focus on what you are doing. If you only have the energy at the end of the day for ten minutes, do ten minutes. Ten minutes with laser-like focus is far better than 30 minutes of merely going through the motions, and ten minutes is infinitely better than nothing.

And A Couple of Other Things…

Get some training before you start dry practice. Practice does not make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect. If you’re doing something wrong, practicing it a bunch of times is only going to reinforce it. Before you invest hundreds of hours into dry practicing, it’s probably a good idea to get some formal training. Videoing yourself can also help with this by identifying what you’re doing wrong. Watch the video at the end of each session. If something is wrong, or could be better, dedicate some time in the next session to improving it.

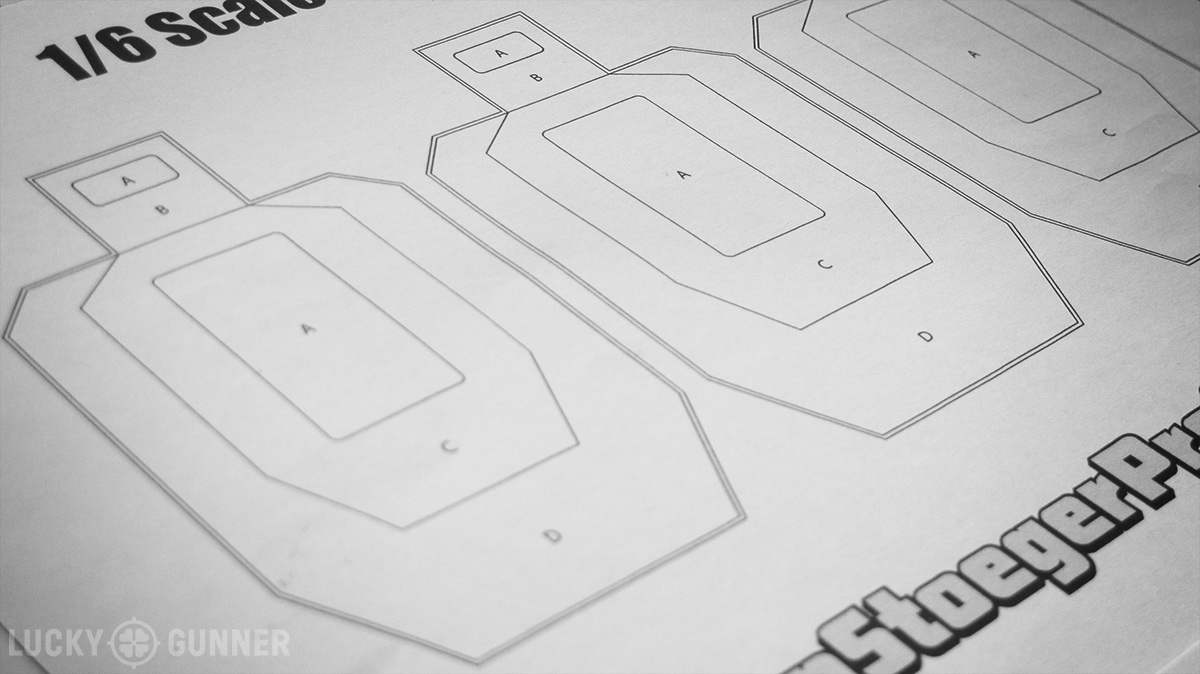

Use scaled-down targets. My dry practice space is pretty limited. I don’t have a 25-yard line to work from. Instead, I simulate distance by printing my own scaled-down targets (usually 1/3 scale IDPA targets). These are available on a number of websites and can be printed on a single piece of paper. At seven yards, one of these targets can approximate a distance of 21 yards.

Try using snap caps. Though it may be debated whether some guns are susceptible to damage from dry firing, as John Hearne put it to me, “if you’re doing enough dry practice that it matters, [using snap caps] probably matters.” Snap caps also let you work on things like malfunction drills, reloads, and other techniques that don’t work with an empty magazine. If you’re a revolver shooter like I am, good luck working reloads without at least six snap caps or dummy rounds. I personally prefer the A-Zoom snap caps because of their durability.

Wrap Up

Last week I mentioned my conversation with John Hearne. He gave me a really good example of the benefit of dry practice. Imagine two people are taught to disassemble a Sig Sauer P220 and will be tested on the skill one year later. One will not see a P220 again until a year later, and the other will have the opportunity to disassemble and reassemble the gun every night. John then asked me to imagine who would perform better on test day. This question is a no-brainer, so let’s put it into a more applicable context.

Let’s assume you need to use your gun in self-defense. Now the question is: would you rather be the person who dry practiced every night for four months or the one who last handled his or her gun at the range four months ago? I know who I’d rather be. Dry practice can’t do everything, but it can let you get a quick training session in, whether you have five minutes or two hours, a shooting range or a quiet garage. Dry practice can keep you current, and it can let you get repetitions in. Dry practice is accessible, and with a little planning, a dry practice session can give you things that even the “hot range” can’t always give you, like low-light work. So stop reading and go dry practice!

Absolutely agree. It is the repetition of movements that build the muscle memories. Manipulation of the pistol controls leads to familiarity, then to proficiency, then to skill, then to automatic. Knowing what your gun will do and won’t do is key to confidence..

Hi Justin,

Thank you for the thought provoking and informative article. What would you recommend to those that own single action only weapons to get the most out of dry practice sessions? My sole carry weapon currently is a Sig P238, but I plan on getting a DA/SA HK USP Compact for Winter carry.

Best regards,

William

William,

You can definitely dry-practice with a single action. I got my start dry practicing with an issued 1911. If you want to work the trigger control/trigger reset you’ll be doing a lot of slide-racking (or partial racking)… Other than that not much changes. FYI, my last pistol was a P238 and I think it’s a great platform and one that will stand up to a ton of dry practice. Hope that helps!

Justin

My daughter qualified for her CCW with my S&W Model 60. I’d used a grinder with a blending disc to de-horn the hammer making it DAO and it was my BUG in a boot on patrol for 13 years. She had a respectable knowledge of handguns at the get-go but the only “shooting” with the little Smith was dry firing the red-colored A-Zoom practice rounds. On qualification day, she and the little Smith amazed everyone. It’s hers now and yes she still cautiously loads it up with newer (she wore the original snap caps out) “ammo” and plays the game of “shooting the bad guy on the TV”.

I want to buy some snap caps to use with my 870 tactical. Is this something I shroud consider? An eBay seller stated, “Up for sale is 3 snap caps I made with some 12 gauge hulls and new shot added for weight. There is a clearly identifiable hole in the rear where a primer would go for easy identification and unusable. Should you want to fill this hole you can use a RTV silicone or a Hot Glue Gun. Practice loading and unloading safely, Failure to Fire Drills, Keep them in the man cave, Etc…. Other calibers available Thanks for looking