The M1 Carbine and the SKS are both excellent firearms. But which 1940s-era semi-auto carbine is better in 2021? That’s not the question we’re trying to answer today. But “showdown” seemed like a much better word for a title than “comparison.” Mostly, we just wanted an excuse to play with the M1 Carbine again and the SKS was sitting there like “hey, can I come play too?” and we said “yes.”

Details are in the video below, or keep scrolling to read the full transcript.

Hey everybody, Chris Baker here from LuckyGunner.com. Despite my best efforts, it seems like you guys are not yet tired of hearing me drone on about the M1 Carbine. So I’ve brought it back out today to put it up against another military surplus favorite; the SKS.

Why compare these two rifles in particular? Well, mostly because I thought it would be fun. But they also have a lot of things in common. They’re both semi-auto military carbines from the 1940s. They were both precursors to the modern assault rifle. They both served above and beyond the military roles they were originally intended for. And they both have a ton of fans among civilian shooters and collectors.

That last part is what I want to focus on today. My goal is not to determine which of these rifles is better than the other. I’m going to compare what the M1 Carbine and the SKS have to offer for you and me. They’re both still really fun and useful rifles, but in different ways.

I’ve owned a few M1 Carbines and a few SKSs over the years. I currently own just an M1 Carbine. I’ll admit to being biased here. The M1 Carbine is probably my favorite long gun of all time (except on days when my favorite is the Marlin 1894). But I still like the SKS and it definitely has some things going for it that the M1 Carbine does not. So I’ll try to be as fair as possible.

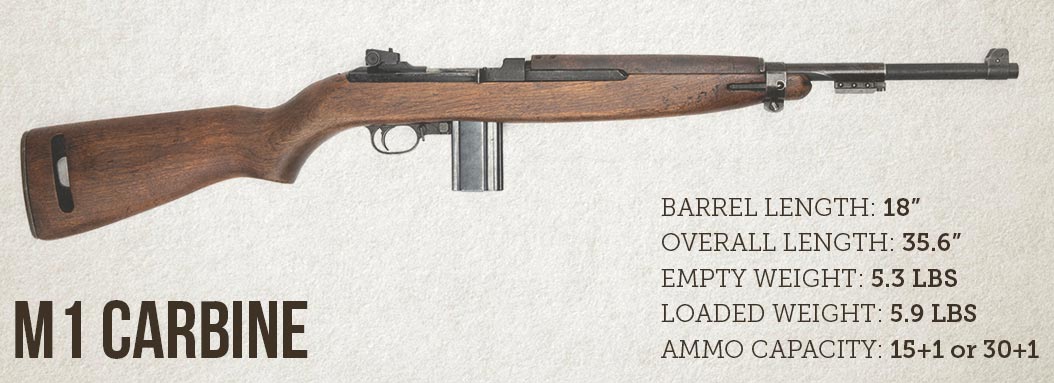

M1 Carbine Specs and Background

Let’s start with some of the basics. The M1 Carbine has an 18-inch barrel and an overall length of about 35 and a half inches. It weighs 5.9 pounds with a loaded 15-round detachable mag. It’s chambered for the .30 Carbine cartridge, which typically consists of a 110-grain bullet traveling at roughly 2000 feet per second.

I’ve already gone into detail on the history and background of the M1 Carbine in other videos, so I’ll let you go back and watch those if you want a refresher. Basically, it’s a WWII-era American military carbine that was intended for non front-line troops, but ended up being used in the front lines anyway. It’s a very compact, lightweight carbine that’s extremely easy to handle and shoot. And it fires a cartridge that’s more effective than the typical handgun, but has less power than a true rifle cartridge.

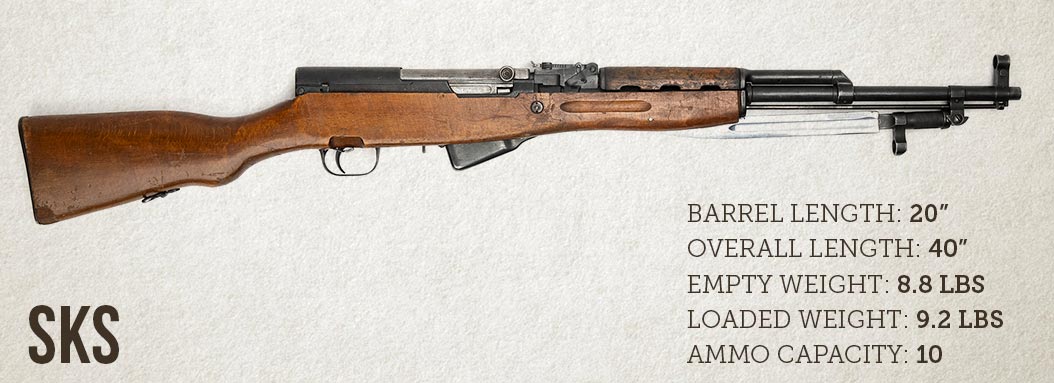

SKS Specs

Next to the M1 Carbine, the SKS feels pretty beefy. It’s over three pounds heavier at 9.2 pounds loaded. It’s also longer with an overall length of 40 inches and a 20-inch barrel.

The intermediate 7.62×39 cartridges feed from a fixed internal 10-round magazine. Most loadings of this cartridge consist of a 123-grain bullet in a steel case. Out of an SKS, the muzzle velocity is usually around 2400 feet per second.

You can load rounds through the top of the receiver one at a time, or ten at once with a stripper clip. The floor plate swings open at the bottom for easy unloading.

Most versions come equipped with a folding bayonet. It’s got a notch-style rear sight that’s adjustable from 100 to a very optimistic 1000 meters.

Some SKS variants have shorter barrels or larger magazines, and some have even been adapted to accept AK-47 mags. In the US, the vast majority of SKS rifles you’ll come across are in the standard military configuration similar to this one unless they’ve been modified by the user.

In terms of ballistics, size, features, and overall capability, the SKS kind of splits the difference between the M1 Carbine and the M1 Garand. If you told a team of Soviet engineers to come up with the cheapest way to combine the best features of those two American rifles, they would probably give you something a lot like the SKS. But that’s not how it happened.

SKS Background and History

The SKS was developed in the Soviet Union in the mid 1940s by the prolific weapons designer Sergei Simonov. During World War II, the Soviet military brass noticed the extended range they could get out of their full power rifle ammo was wasted when most fighting took place inside of 300 yards. So they developed the shorter 7.62×39 cartridge that would allow units to carry more ammo and overwhelm enemies with a higher volume of fire.

At the end of the 1940s, the first SKS carbines utilizing this new cartridge were issued to Soviet troops. However, by that time, the Soviets were also testing the early prototypes of the AK-47. So, the SKS didn’t have a very long service life in the Soviet Union as a primary infantry weapon. It was rendered obsolete by the AK-47 before it ever got much traction.

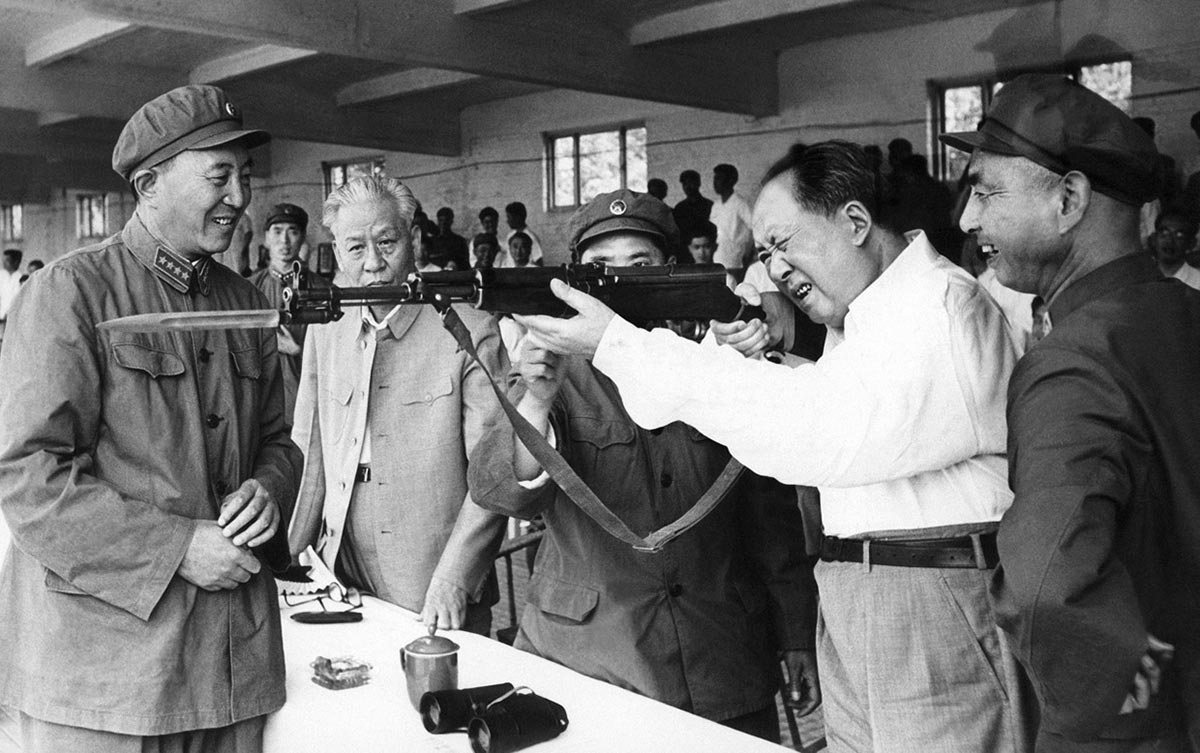

But the Soviets didn’t let all those brand new carbines go to waste. They wanted to make sure their communist allies around the world were not trying to liberate the proletariat with outdated weapons. So in the 50s and 60s, the Soviets handed out SKSs like candy to left-wing guerilla fighters and insurgent forces all over Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The Chinese army was especially fond of the SKS. With help from the Russians, they started producing their own variant, called the Type 56 Carbine. The Chinese ultimately made about 8 million of those compared to less than 3 million SKSs produced by the Soviet Union. The SKS was also produced in other communist countries like Yugoslavia, Romania, and North Korea as well as some commercial variants.

Fast forward to the present day. AK pattern rifles have almost completely supplanted the SKS around the world for combat use. That has allowed millions of surplus SKS carbines to make their way into the US and Canadian civilian markets. Here, they are probably known first and foremost for being very affordable. Back in the 90s, you could pick up an SKS for well under $100. Not too long ago, the average price was still only about 300. In today’s market, the most affordable SKS variants are in the $400-500 range. But that’s still at least a couple of hundred bucks less than most other centerfire semi-automatic rifles.

The SKS I have here is Russian-made. Like many of these surplus rifles, the stock looks a bit rough, but overall, it’s in decent shape. At the moment, it’s basically in its original configuration. But that’s almost become the exception rather than the rule. People just love to tinker with and modify the SKS. And that’s the first comparison I want to make between these two carbines.

Mods and Accessories

There are plenty of modified M1 Carbines out there, but owners of those guns seem to be a little more reluctant to make any changes to those compared to the SKS. In certain circles of gun culture, there’s a kind of reverence that surrounds American WWII-era firearms. It’s almost considered taboo to even consider modifying one of them.

If you saw my last video on the M1 Carbine, you might remember that I do not subscribe to those taboos. I wouldn’t be too quick to make permanent changes to a gun with real collector value. But otherwise, I believe guns were meant to be shot and if you can do anything to make them shoot better or make them more enjoyable, then go for it. So I’ve replaced the wooden handguard on my M1 Carbine with an Ultimak picatinny rail and a Swamp Fox Optics Justice red dot sight. The Ultimak rail is very well-made. It holds zero if it’s installed properly and it sits low enough to let you get a good cheek weld on the stock. I’ve also got the Olongappo Outfitters mag pouch here on the buttstock, which I think is an improvement over the original GI mag pouches.

Other than those two things, I haven’t seen many non-GI M1 Carbine accessories that seemed worthwhile to me. Some of the commercial variants of the M1 Carbine have deviated from the original design a little bit. But as far as end-user modifications, the most common changes are usually limited to various types of optic mounts.

The aftermarket situation for the SKS is… I guess the polite way to say it would be more robust. Maybe it’s because the SKS is inexpensive. Maybe it’s because they’re communist rifles. For whatever reason, people tend to treat the SKS less like a precious military antique and more like a cheap platform to experiment with.

There are a ton of parts and accessories for these rifles. You can choose from a wide variety of optic mounts, polymer pistol grip stocks, vertical foregrips, bolt-on muzzle devices, extended magazine kits, bipods, and much, much more. Unfortunately, most of these things are hot garbage.

In recent years, the SKS tricked out with cheap mods has become a running joke and the target of much online ridicule. Some of that might be well deserved. I don’t have a problem with tinkering with an SKS in theory. I’ve seen a few SKS mods that were very well done, but most of them required some technical skill or an actual gunsmith. As a whole, the drop-in and bolt-on parts probably create more problems than they solve. In particular, the magazine mods tend to be really unreliable. And most of the optic mounts don’t hold zero or they position the optic where it’s impossible to get proper eye relief or a cheek weld.

We did read some good things about the red dot mount from Bad Ace Tactical. Since the SKS factory iron sights leave something to be desired, we decided to give that mount a try. Installation was easy. The mount fits in the existing slot for the rear sight assembly. So you end up with a piece of picatinny rail hanging out over the action. There’s a relief cut in the back end of the rail so you can still use stripper clips.

We mounted a Swamp Fox Liberator II red dot and took it out to the range. After a couple of hundred rounds, it was still holding zero just fine. But, I was getting quite a few failures to eject — about one in every ten or twenty rounds fired. Judging by the dents and dings that appeared on the bottom of the rail, it looked like the shells were bouncing off the rail and back into the action.

However, after we removed the rail and went back to the factory iron sight, we still had some ejection problems. I had not fired this rifle much before we installed the optic. So, I can’t say for sure whether the rail was the real cause of the issues, or if there’s something else going on with this rifle. I couldn’t find anyone else complaining about that problem, so the rail might not be the cause. Either way, I wasn’t really happy with the lack of cheek weld I was getting with the optic mounted. If I were to try the mount again in the future, I’d want to add a cheek riser on the stock to go with it.

Ammo and Accuracy

Okay, that’s enough about mods and accessories. Let’s talk about actually shooting these things. We’re gonna look at ammo, ballistics, and accuracy.

Both of these carbines and the cartridges they fire have reputations for being inaccurate and for being useful only at limited range. Those things are both mostly true. At least by today’s standards. But we also don’t want to sell these guns short. Most M1 Carbines and SKSs have an accuracy potential of around 3 to 4 MOA. You can tinker with them and experiment with ammo and sometimes get them down to one and a half or two, but 3 to 4 MOA is typical.

Back in the 1940s, 4 MOA was considered pretty good, especially for a military rifle. In terms of pure mechanical accuracy potential, they can’t hold a candle to a decent AR or even a modern budget-grade bolt action rifle. I wouldn’t want to try to shoot at deer at 300 yards with an M1 Carbine or an SKS. But if you just want to make some noise on steel, you can have a lot of fun with these guns, even at that range.

I shot some groups on paper at 100 yards and true to form, I averaged about 4 inches with the SKS. The M1 Carbine did slightly better at 3.3 inches.

Later, we took them all the way out to 300 yards, which is the maximum distance at our range. That’s not particularly far for most rifle cartridges, but both the .30 Carbine and 7.62×39 start to drop like a rock after about 200 yards.

Using a 100 yard zero, .30 Carbine should be hitting about four feet low at 300 yards. With a little help from Kenneth, who was my cameraman/spotter for the day, I had had my holdover figured out within about four rounds, and I was getting consistent hits on steel.

7.62×39 doesn’t drop nearly as fast as the .30 Carbine. With a 100 yard zero, most loads will hit around 25 to 30 inches low at 300 yards. But, since I had the iron sights back on the SKS, I just moved the rear sight up to the 300-meter position. At 300 yards, that meant I had to aim just slightly below the target and I was getting hits on three out of four shots.

That’s not bad for a couple of inaccurate rifles. And with the SKS in particular, there is something gratifying about ringing steel at 300 yards using crappy sights and cheap steel-cased ammo.

Terminal Ballistics

If you actually want to use one of these rifles for something practical, like hunting or self-defense, or defending your family during the coming cyborg uprising of 2029, you might be more concerned about the terminal ballistics of these two rifles. That is one area where the SKS definitely has some advantages. The typical 7.62×39 bullet has about 12% more mass and 20% more velocity than .30 Carbine.

If you look around, you can find numerous official and unofficial reports of how both of these rounds have performed on the battlefield. But most of those reports involve full metal jacket ammo, so we have to take them with a grain of salt. We are not limited to FMJ. We can use soft point and ballistic tip loads. Expanding bullets have a major impact on the wounding potential of these two cartridges in particular. They create a bigger temporary stretch cavity that is more likely to cause wounding and tearing that radiates out beyond the path of the bullet itself. These two intermediate cartridges really need to deform in order to transfer that energy to the surrounding tissue. I like the Hornady SST bullets for 7.62×39 and the Hornady FTX for .30 Carbine. But some of the basic soft point loads also expand reliably.

If I thought I was going to be hunting a lot of medium-sized game, I would definitely lean more toward 7.62 and the SKS. But for stopping a violent human attacker at close range, I doubt there would be much of a practical difference between an SKS and an M1 Carbine loaded with good soft point ammo. The increased ammo capacity, shorter overall length, and ease of shooting the M1 Carbine more than make up for any potential loss in ballistic effectiveness.

Reliability

For practical use, I think reliability should actually be a higher priority than ballistics. Both of these rifles can be reliable, but since most of them are at least several decades old at this point, it’s not uncommon to run into issues.

In front of me here, I have an M1 Carbine that has been plugging along flawlessly, but I had to do some work to get it there. This particular SKS has been giving me some feeding issues that I haven’t had a chance to troubleshoot yet. However, the general impression I’ve gotten is that the average unmodified SKS tends to feed more reliably than the average M1 Carbine. I can’t prove that, it’s just what I’ve gathered from having owned a few of these rifles and from hearing about other people’s experiences.

The M1 Carbine has the added variable of detachable magazines. Those can be a weak point in the feeding cycle if you don’t have good ones. There are also a bunch of commercial M1 Carbines out there and those are usually more problematic than the carbines made during the war.

On the other hand, the SKS has the slamfire issue. The firing pin in the SKS is supposed to jiggle around freely inside the bolt until the hammer hits it. But sometimes, it can get stuck in the forward position, either from corrosion or from the cosmoline grease they used to preserve these rifles for storage. That can easily lead to a slamfire. That’s when a round discharges when you release the bolt or when the bolt cycles. Sometimes it manifests as just an occasional surprise two-round burst. In a worse case scenario, the gun goes full auto and fires all ten rounds before you even touch the trigger.

That’s not good. And it’s a fairly common issue with the SKS. I’ve seen slamfires happen with two of them. The easiest way I know of to avoid it is to install a firing pin from Murray’s Gunsmithing. It comes with a return spring that holds the firing pin in the rear position until the hammer hits it.

Having said all of that, if you get either an M1 Carbine or an SKS in good condition, replace any worn springs or parts, keep it cleaned and lubed, and use decent ammo, both can be incredibly reliable.

The Verdict

Now, I know what you’re thinking. “Chris… you’ve been at this for almost 20 minutes now and you still haven’t told me which rifle is better. I’m lost. I need your guidance. I want to buy a pointless old gun for… reasons, just tell me which one to get.”

Okay, fine. If you’re going to twist my arm, I’ll pick one for you. Get an M1 Carbine. Obviously. They are just more fun than the SKS. As a means of transporting bits of lead from point A to point B, the SKS is a fine instrument. But it’s clunky and heavy. It gets super hot if you start shooting it like the ammo is 12 cents per round again. The safety is a negligent discharge waiting to happen — it’s the same shape as and right next to the trigger.

On the other hand, the M1 Carbine is light as a feather. Probably an eagle feather because the M1 Carbine smells like freedom instead of cosmoline. It’s got a better trigger. The safety is safer. It holds more bullets. It has better iron sights and better optic mounting solutions. If you’re really into the whole bayonet thing, you can get a bayonet for your M1 Carbine. And they’re actually sharp. Kind of.

The only real downside is the price. Even with SKS prices going up, they still cost about half of what you’ll pay for a decent M1 Carbine. And you still need some magazines. And .30 Carbine ammo is more expensive and sometimes more difficult to find than 7.62×39.

If your primary concern is home defense or you’re preparing for the cylon invasion and you can afford an M1 Carbine, you probably shouldn’t buy an M1 Carbine. Buy an AR-15 if they are legal in your state. They’re also pretty fun but generally less of a headache to own. An M1 Carbine can be your second rifle. And if you’re still curious, an SKS can be your third rifle. And then you can sell it in a couple of years when they’re 700 bucks.

But if you cannot afford an M1 Carbine, the SKS is a pretty good rifle to see you through the end of the world. Yeah, they’re kind of dated, but they’re also rugged and usually pretty reliable if you don’t mess with them. For any kind of defensive use, I would definitely trust a surplus SKS over the kind of AR or AK that $500 will get you in 2021.

So there you have it. The M1 Carbine is freedom loving fun for filthy capitalists. The SKS is personal protection for the poors. And I am the very model of a modern major general. Buy some ammo from Lucky Gunner. See you guys next time.