You ever get that feeling — while you’re buying bed sheets, horse feed, and patio furniture — that what’s really missing from your life is a tackle box revolver? I know, me too! Sears Roebuck also believed their customers felt that way, so they asked High Standard to design just such a revolver. And in 1955, we got the High Standard Sentinel — a 9-shot .22LR wheel gun.

Details are in the video below, or scroll down for the full transcript.

Hello everybody, I am Chris Baker from LuckyGunner.com. Today, I don’t have any advice for you. I’m not making any recommendations and I didn’t do any tests. I just have an interesting old gun I want to talk about. So with apologies to Ian McCollum, who does a much better job with this kind of thing, we are going to take a look at the High Standard Sentinel.

It’s a nine-shot double action revolver chambered for .22 LR. You guys know I love revolvers and small caliber pocket pistols, especially when they are well-designed. The Sentinel is not an especially well known gun, but it’s got some well thought-out features that were innovative for the time, including a couple that I’d like to see on more of today’s snubby revolvers.

Early History of the High Standard Sentinel

Various iterations of the Sentinel were made from 1955 until 1984. This particular sample is from 1969. In that era, Smith & Wesson and Colt were the dominant names in double action revolvers. High Standard had been making guns since the 30s, but they didn’t have any revolvers. They were best known for their semi-automatic .22 target pistols.

The Sears Roebuck department store chain was a partner and major shareholder of High Standard at the time. Sears asked them to design a so-called “tackle box” revolver. It had to be a low-cost double action .22LR with a nine-shot capacity, probably to compete with other 9-shot .22 revolvers on the market like the H&R 900 series.

The man High Standard assigned to this task was a 33 year old designer named Harry Sefried. Sefried had recently come from Winchester where he had worked on a number of rifle designs, but he’s probably better known for the work he did at Ruger in the 60s and 70s. Among other things, he helped design the Redhawk, Security Six, the Mini-14, and the rotary magazine for the Ruger 10/22.

Back at High Standard, Sefried completed the design of the Sentinel from start to finish in just three months. He borrowed elements from several existing designs and came up with a couple of his own. It’s fairly unique for a mid-century revolver design. Guns Magazine went as far as to call it the “first new revolver in 50 years” (June 1955 issue. PDF here.)

The only screws it has are the grip screws. The frame is in two pieces held together by these two pins. Some earlier versions of the Sentinel have just a single pin.

The frame is aluminum with a steel cylinder and barrel. It weighs 20 ounces unloaded – about as much as an all-steel 2-inch Smith & Wesson J-frame, but it’s a bit larger than a J-frame. It’s a lot closer in size to something like a Ruger SP101. So it’s not as light as a modern 22 snubby like the Ruger LCR or a Smith 43C, but it is light relative to its size.

Sentinel Variants and Changes

Sears offered the Sentinel under their J.C. Higgins brand and called it the Model 88 Fisherman. There was also a version made for Western Auto labeled as the Revelation Model 99.

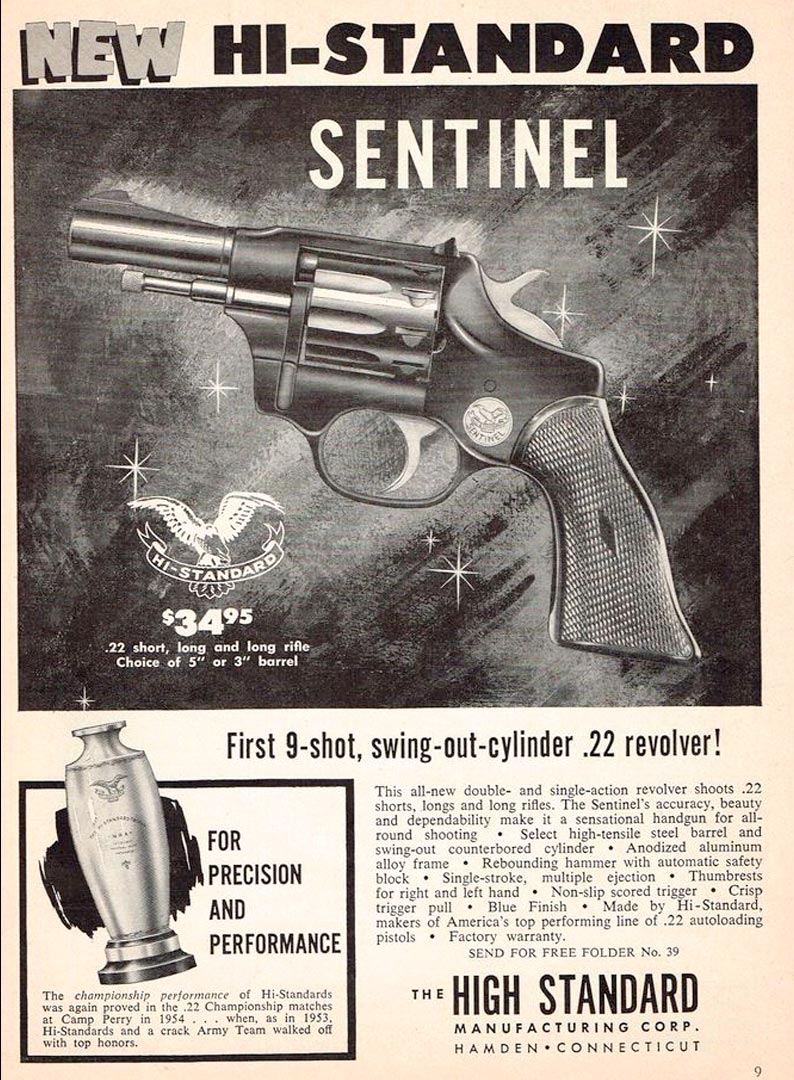

In 1955, the advertised price for the Sentinel was $34.95. That is roughly equivalent to $375 today, which is close to what a modern budget revolver costs. Just three or four years ago, it was not uncommon to find pre-owned Sentinels in like-new condition for well under $300.

But, just like everything else in the firearms market, the prices have risen dramatically in the last couple of years. We picked up this one for about $500 and it’s far from pristine. It’s in great shape mechanically – it doesn’t appear to have been fired much at all. But the nickel finish is well-worn in several places.

The original Sentinels were available with 3 or 6-inch barrels and a black oxide finish. The two-inch snub nose models and the nickel plated finish like this one didn’t become options until a year or two later. Up until 1974, Sentinels had plastic grips. Some of them were two piece like this one with a screw on either side. Others were a single piece with a screw at the base.

The snubby models had a round butt grip frame while the longer barrels had a more traditional square butt. The square butt frames are supposedly very comfortable to use – that comes up in a lot of the articles about these guns. Personally, I don’t care much for the grip on this round butt model. For double action shooting, it needs more meat here behind the trigger guard. It could use something like one of the grip adapters you often see installed on old-style Colt and Smith revolvers.

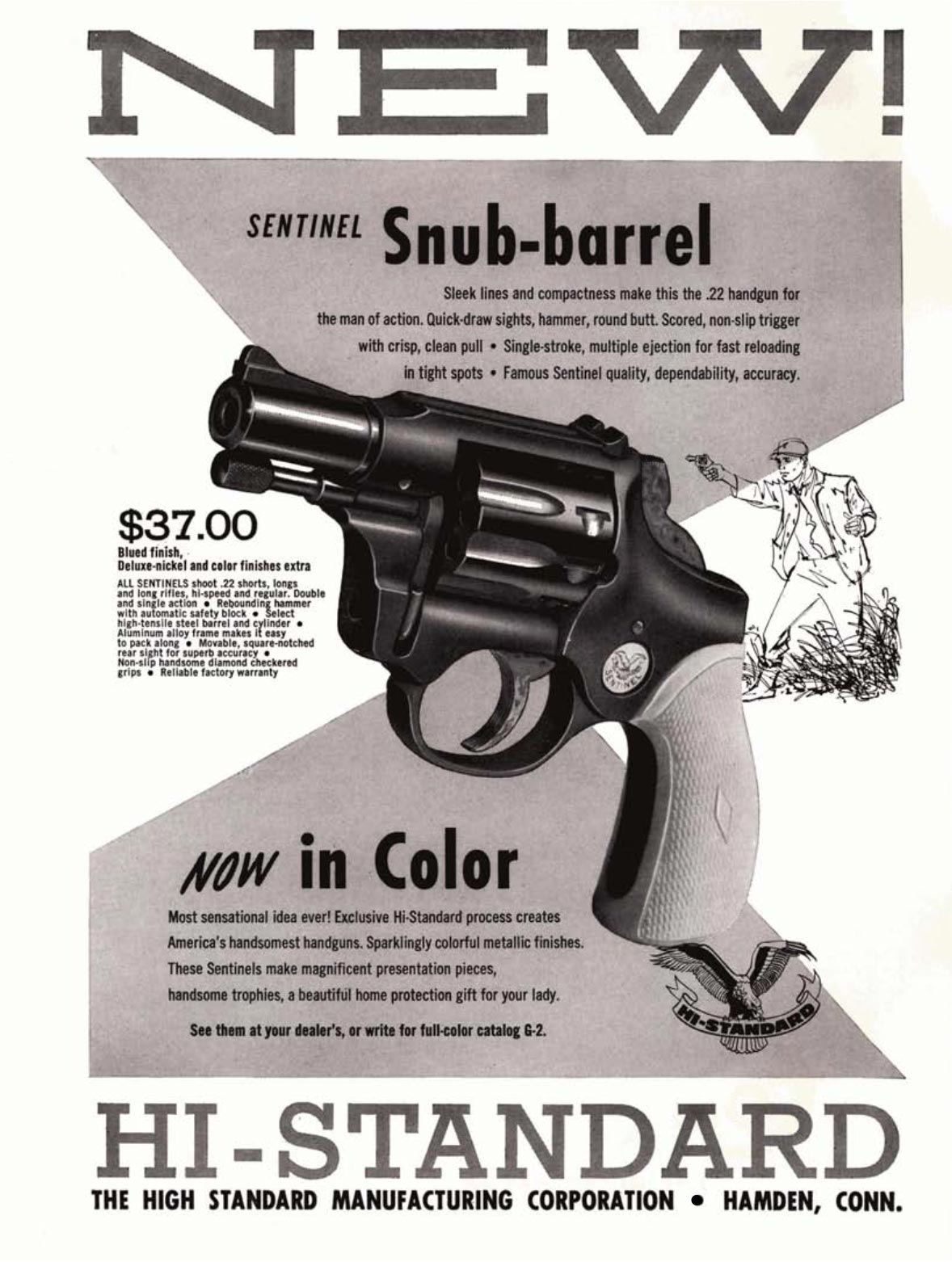

Some of the early 2-inch Sentinels were also available with a colored finish they called Dura-Tone. They came in Pink, Turquoise, and Gold and they’re among some of the most rare variants of the Sentinel today. These were not the first revolvers marketed specifically to women. But the Sentinel is the first gun I’m aware of that came in special colors to try to appeal to female shooters (or, more likely, to men who thought that’s what their wives wanted.)

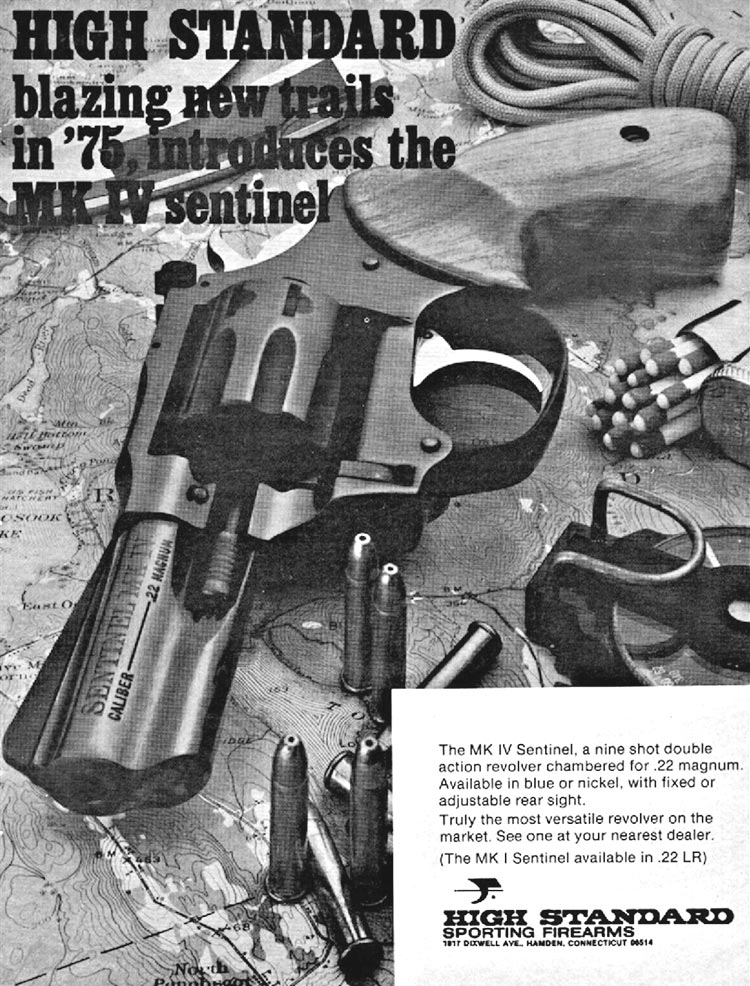

The Sentinel went through several minor changes over the years designated by model numbers starting with R-100 through R-109. In 1975, High Standard discontinued the R-series and made some bigger changes to the design. The Sentinel MK I was a .22LR with a full barrel shroud, all-steel construction, and wraparound wood grips. The MK IV was the same thing chambered in .22 Magnum. They made both of those with different barrel lengths and styles of sights. There was even a version that came with interchangeable .22LR and .22 Magnum cylinders.

High Standard also released a MK II and MK III Sentinel, but those were actually re-branded Dan Wesson .357 Magnum revolvers. They only did that for a couple of years in the mid 70s. The .22 models continued production until about 1984.

High Standard Sentinel Design and Features

Ejector Rod and Cylinder

Let’s take a closer look at this particular gun. The first thing that stands out is that there’s no cylinder release latch on the frame. To open the cylinder, you just pull forward on the ejector rod and it swings right out. You push on the rod to eject the empty shells just like any modern double action revolver.

Early versions of the Sentinel did not have a spring-loaded ejector rod. So you had to manually return the ejector into the cylinder before closing it. You can almost always spot one of these early models because there will be ugly scratch marks on the frame from where previous users tried to close the cylinder without pulling the ejector back in.

Hammer Block Safety

All versions of the Sentinel feature an internal hammer block safety. The firing pin is fixed – you can see it right there on the hammer, so this does not have a transfer bar system. But there is a little piece in there that prevents the hammer from moving all the way forward unless the trigger is pressed.

Right now, I can press on the hammer and it does not move – it’s resting on that hammer block. The firing pin is not protruding into the cylinder window, so it would not be touching the rounds if the gun was loaded. But if I pin the trigger to the rear, now you can see that the hammer can go forward a little more. That means this gun should be relatively drop safe, and it’s safe to carry with all nine chambers loaded.

Trigger

The double action trigger on this particular gun is… not great. It’s very heavy. It breaks at about 14 pounds. The trigger face is squared off and serrated like a target style trigger, which is actually counterproductive for double action shooting. At the very end of the trigger pull after the action is locked up, there’s a little extra travel you have to pull through where you would expect the trigger to have already broken. Sometimes it feels like the trigger wants to bind up right there a little bit.

The single action is not bad. I measured that at five pounds, but it feels lighter than that, probably because the double action is so heavy. I guess if you bought this gun to shoot snakes and squirrels from your fishing boat, you’re probably going to use it primarily in single action. That said, some of the early snub nose versions came with a bobbed hammer, clearly meant as more of a self-defense oriented pocket pistol. The ad here shows what looks like an outdoorsman kind of guy, but the ad copy says it’s a handgun for “the man of action” – whatever that means. It also says it would make a “beautiful home protection gift for your lady.”

Unfortunately, if the trigger on this gun is typical for a Sentinel, the shooter would need to have quite a bit of experience with double action shooting to be truly proficient beyond just a couple of feet.

Cylinder Notches

I know some of you probably cringed when I dry fired this thing a minute ago. It’s generally a bad idea to dry fire older guns, especially older rimfire guns. The problem with dry-firing .22s is that when there’s no cartridge rim for the firing pin to strike, it hits the chamber face instead. That can cause wear on the chamber and on the firing pin, and oftentimes the firing pin will just break. But Sefried included a little design feature to help mitigate that issue.

The cylinder face has these slots machined into it. So if there’s no cartridge, that relief cut prevents the firing pin from striking the cylinder face. I still would not make a habit of dry-firing this gun simply because its old and replacement parts are hard to find, but it’s nice to know that the occasional dry fire is probably not going to immediately ruin it.

Sights

Finally, I want to point out the sights on this gun. They are excellent for a snub nose revolver, whether we’re talking about 1955 standards or 2022 standards. Sefried was proud of the accuracy this revolver was capable of. Even though he was working within some tight budget restrictions, he didn’t just put an integral trench-style rear sight on the gun. He found a way to get a windage-adjustable dovetail rear sight in here. The rear sight notch is a decent size with a tall front sight, but they’re still low profile enough to be carry-friendly. From a bench at 25 yards I was getting 3-inch groups with CCI Mini-Mags. That’s not target pistol accurate, but definitely respectable for a 50 year old snubby. I’ve tested modern service-size pistols that can barely shoot 3-inch groups. So this is a gun that deserves good sights and I’m glad it has them.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, for me, a big part of what makes a revolver fun to shoot is a smooth double action trigger around eight to twelve pounds. After the first box of ammo, this trigger is a bit of a chore to deal with. I love the design and the look of this gun. But between the trigger and the grip, it would not be my first choice for a fun, old .22 plinking pistol. I probably wouldn’t try to use it as a defensive training revolver either. If you like shooting single action, you might have more fun with it. I have noticed the non-snubby models tend to sell for a little less than the 2-inch versions. It’ll probably never happen, but I’d love to see someone try to revive and improve this design. A lightweight 9-shot .22 Magnum with a 3-inch barrel would be especially cool.

That’s all I’ve got for today. Hope you guys enjoyed it. Next time you need some ammo, be sure to get it from us with lightning fast shipping at LuckyGunner.com.