The first Smith & Wesson J-frame revolver hit the market in 1950, but the basic design it’s derived from goes all the way back to 1896. There’s a lot to learn from looking at how this iconic concealed carry favorite has changed and evolved over time. In some ways, it’s a window into the changes in defensive shooting doctrine over the years. Unlike the Evolution of the Beretta 92 that we did a while back, this post isn’t intended to be a guide to every technical change made to S&W snubbies in the last century — it’s more about the “whys” behind those changes. So, let’s explore the evolution of the Smith & Wesson snub nose.

Watch the video below for details, or scroll down to read the full transcript.

Learning From History

We are coming up on a full year since we started this series on pocket pistols… which is only about six months longer than I thought it might last. Whenever I start a new series, I usually have a basic outline of topics, but once I dig into it, I always come across things I want to talk about that weren’t part of the original plan. In this case, I happened to find an old Smith & Wesson .32 Long snub nose at a local gun shop for a good price. As I was looking at it, I started thinking about how it’s pretty similar to a modern J-frame Smith on the surface, but if you consider all the little details, it’s not really the same at all.

A lot of the most popular guns around today are based on designs that are decades old. There is a lot we can learn by looking at how these guns have changed and evolved over the years because those changes often tell a story about the way people thought about marksmanship, or concealed carry, or even gunfighting.

Smith & Wesson made this revolver around 1954 or ‘55. Collectors today would call it a “Pre-Model 30” because it was made before Smith & Wesson assigned model numbers to everything. At the time, the official name was simply the “.32 Hand Ejector.”

The 1950s was a period when Smith & Wesson was making some new guns that would become game-changers in the small-frame snub nose market. But this little .32 wasn’t really part of that — it was more like a relic of the era that was passing.

If you compare this gun to a modern J-frame, the first thing you might notice is that it’s smaller. They are relatively the same size in most dimensions but the cylinder and the cylinder window in the frame are about a quarter inch shorter. That’s because this isn’t actually a J-frame at all. It’s an I-frame, which pre-dates the J-frame by more than 50 years.

From Hand Ejector to J-Frame

Smith & Wesson launched their famous Hand Ejector line in 1896. That’s the basic design all their revolvers are still based on today. The first one was a .32 Hand Ejector — an I-frame very similar to this one, only with a longer barrel. Three years later, they came out with a .38 Special Hand Ejector, which they built on the slightly larger K-frame. That’s the iconic revolver that would eventually receive the designation of the “Model 10.” S&W marketed both revolvers as police sidearms but a few decades into the 1900s, the .32 Long cartridge was beginning to be considered underpowered for that role.

So as .38 Special became more dominant, there was a growing market for a short-barreled small-frame revolver in that caliber. Unfortunately, the I-frame cylinder was not long enough because it was designed for the .32 Long cartridge which, despite the name, is shorter than .38 Special ammo.

So in 1950, Smith & Wesson introduced a new frame size. The J-frame Chief’s Special was basically an I-frame with a longer cylinder and cylinder window. It only held five rounds of .38 Special versus six rounds of .32. That lower capacity didn’t stop it from being a massive success.

In 1961, Smith & Wesson decided they didn’t need two different small frame sizes, so they discontinued all the I-frames. After that point, any small frame .32s Smith & Wesson built used the J-frame.

The .38 Special J-frames were especially popular with police. In the 1900s, law enforcement sales really drove the handgun market, even more than today. So Smith & Wesson made a lot of these changes we’re going to talk about in response to what police were saying they wanted as they carried and used these guns on duty.

Target Shooting Versus Practical Self-Defense

Even though S&W intended this .32 snub nose to be used for personal protection, like a lot of revolvers from that era, there are a few indications that it was designed by people who were mostly familiar with single action target shooting. For most of the 20th century, police and anyone else who took handgun shooting seriously were most likely to practice and compete using some form of slow-fire bullseye shooting. This encouraged thumb-cocking the hammer for every shot. There’s evidence of this mentality when we look at the sights, the grips, the trigger, and, of course, the presence of the hammer spur.

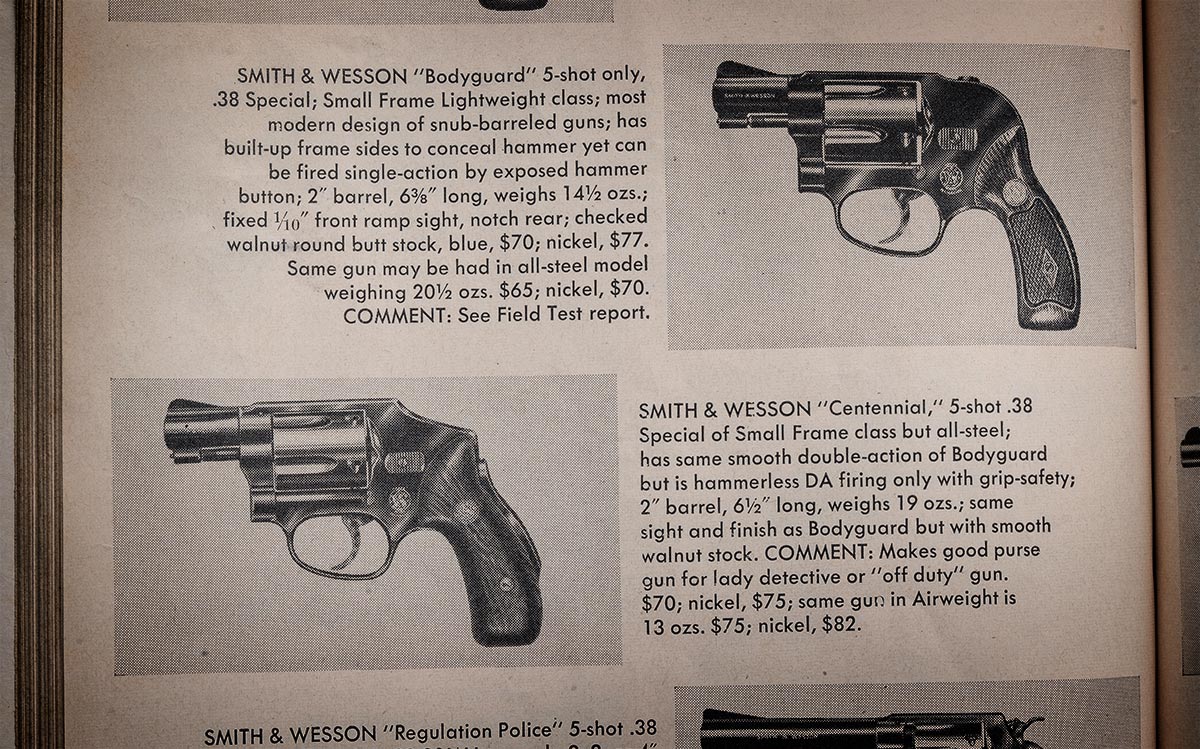

Some of the modern J-frames also have a hammer spur, but most of the current models are double action only. They conceal the hammer inside the frame. You give up the single action feature to make the gun more snag-free and easier to draw. Smith & Wesson made the first so-called “hammerless” J-frame in 1952 called the “Centennial,” which came with a grip safety that I think hurt its popularity. A few years after that they introduced the original Bodyguard. It was a J-frame with a hammer spur shrouded only on the sides so you could still cock the hammer manually. But even after these models came out, for a long time, most J-frames had the standard exposed hammer spur. I don’t believe that really started to change until about the 1990s with the rise of the modern concealed carry movement.

Trigger Evolution

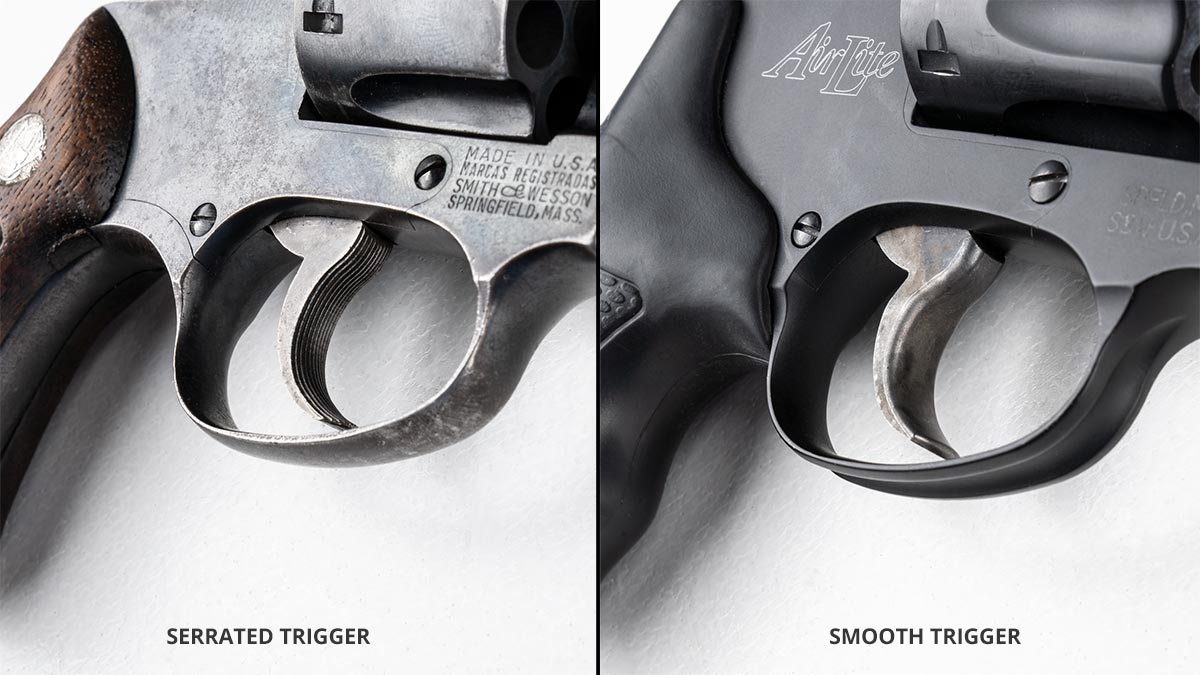

If you look at any current-production J-frame, it’s going to have a trigger with a smooth face. Back when Smith made this one you had the option of getting a trigger with a serrated face. That’s how most were made. That might have some benefits when you’re shooting the gun single action and you’re pressing the trigger with the pad of your finger. Shooting double action, you need more leverage on the trigger. Most people get better results if they use the first joint of their finger.

If you hold up your hand and move your finger in a motion like you’re manipulating the trigger, you’ll notice that whole first segment of your finger doesn’t go back in a straight line. It moves along an arcing path. So with a good trigger press, your finger is going to kind of roll across the face of that trigger. Attempting that with a trigger that has a serrated face… kind of sucks. After the first box of ammo, it starts to feel like a cheese grater. I’m guessing that the serrated triggers were eventually dropped as a cost-saving measure. The side benefit is that the smooth triggers make the guns much better for double action shooting.

Evolution of the Sights

In profile, the fixed sights on this old gun don’t look any different from the fixed sights on a lot of modern J-frames. If you actually try to use them, you’ll immediately notice that both the front ramp and the rear notch are much narrower. The assumption was that you would point shoot at close range and the sights were for target shooting. The narrow sights give you more precision so you can hit that bullseye at 25 or 50 yards. And I can confirm that this little gun is unbelievably accurate. Thanks to the inherent accuracy of the .32 Long cartridge, it will shoot better groups than just about any other handgun I’ve owned.

But we’ve learned from the experiences of people who have actually been in gun fights. It turns out that sometimes sights are really useful at close range, if you can actually see them. So for close range defensive use, I would much rather have the wider sights found on the modern J-frames. Even those are not all that great, but the wider ramp and notch are much easier to see. With a little bright paint on the front sight, I have a usable sight picture I can acquire very quickly. And we’ve also got some new J-frames with pretty good fixed sights like the bigger U-notch and white dot front sight on this Model 43C.

Evolution of the Grips

One more sign of the fixation with single action target shooting is the grips. The factory checkered walnut stocks certainly look nice, but they aren’t ideal for a defensive revolver. The main issue is that they don’t fill in this area here behind the trigger guard. Some shooters call this area the “sinus.”

Today, J-frames come with many different types of grips and there is a plethora of aftermarket options. Nearly all of them, to some degree, will fill in the sinus.

That does a couple of things. First, it changes the orientation of your hand. With the original grips, your trigger finger has to contort downward at an awkward angle. If you want to shoot double action, you’ll probably end up pressing on the very top of the trigger. That’s where the resistance is greatest.

The grips on modern J-frames lower your fingers on the frontstrap. They put the trigger finger closer to being in line with the center of the trigger.

The other benefit of these grips is that they tend to fill most people’s hands better. They’re more comfortable and it makes the gun easier to control because the grip won’t shift around in the hand as much under recoil.

It’s actually not fair to call this a modern innovation. Grips with this same basic shape actually date way back to the 1920s or 30s. Before that, there were grip adapters available that accomplish the same thing. Some people believed that the lower hand position was better for single action target shooting, not just for shooting the gun double action.

Newer J-frames offer a lot of other upgrades, like the larger cylinder release latch and shrouded ejector rod. Around the time this gun was made in the 1950s, Smith & Wesson was starting to experiment with lightweight aluminum alloy frames. Today, they have continued to push the envelope on using modern materials, making small frame revolvers as light as possible. And I think that, more than anything, is what keeps the J-frames relevant today. They can be as light as any pocket semi-auto, but they give you a little more grip to hang on to.

Of course, I went into more depth on that topic on our Pocket Pistols Versus Snub Nose Revolvers video. You can find that and the rest of our Pocket Pistol Series along with the full text transcripts here. We are getting close to the end of our Pocket Pistols Series but we’ve still got a few more topics to cover before we wrap it up. Be sure to subscribe because you don’t want to miss a thing.