The legendary Marlin 1894 has long been a favorite among shooters, despite a troubled manufacturing history, especially during the Remington years. With Marlin now under Ruger’s ownership, we’re looking at whether the new 1894 Trapper in .44 Magnum lives up to its iconic reputation.

We’re also tracing the 1894’s lineage from its 19th century origins through the infamous “Remlin” era to Ruger’s revival. From black powder to bankruptcy and back again, it’s the saga of a gun that refused to die.

Details are in the video below, or keep scrolling to read the full transcript.

Hey everybody, I am Chris Baker from Lucky Gunner and today I’m looking at the Marlin 1894 lever action rifle. And I’m going to pay special attention to this new Trapper model in .44 Magnum. As you may already know, Ruger acquired Marlin Firearms a couple of years ago and took over all the manufacturing. That came after several painful years of infamously poor quality control when Marlin was owned by Remington. Is Ruger doing any better?

Early History

Before we answer that, let’s look at the history of the Model 1894, where it fits in Marlin’s lineup, and how Remington messed it all up. For the last few decades, Marlin’s lever action catalog has included three basic centerfire models: the 1895 for large cartridges like .45-70, the 336 for intermediate cartridges like .30-30, and the 1894 for revolver cartridges like .44 Magnum, .357 Magnum, and .45 Colt.

While the 1895 is essentially a modified 336 action, the 1894 is a distinct design, easily recognizable by its flat bolt that sits flush with the receiver.

John Marlin first started producing lever actions in 1872 but he had trouble making any real headway in a market completely dominated by Winchester. His breakthrough came with the Model 1889 – the first lever action with a solid steel top receiver that ejected to the side. A lot of shooters preferred this design over the top-ejecting Winchester because it was stronger and better protected the action from the elements.

Five years later, Marlin introduced an improved version called, believe it or not, the Model 1894. It featured a shorter receiver designed to chamber some of the less powerful black powder cartridges meant for small and medium game. It was a big seller for Marlin for the first couple of decades. But after WWI, the company faced some turbulent times. Production of the 1894 was sporadic through the 1920s, and ended completely sometime in the early 30s.

The New Model 1894

That might have been the end of the 1894 if not for the rising popularity of a certain revolver cartridge a few decades later. In the 1960s, Marlin recognized the demand for a carbine chambered in the powerful new .44 Magnum. In 1963, they first tried offering a .44 version of the Model 336. But the cartridge was too short for that action, and the gun never functioned properly. It was discontinued after just one year.

But Marlin didn’t give up on the idea. They went back to the old 1894 design, made a few modifications, and in 1969, introduced the New Model 1894.

The .44 Magnum carbine was an immediate commercial success. In 1979, they expanded the line to include .357 Magnum, and they added .45 Colt in 1989. Over the years, the 1894 has been offered in numerous configurations with various barrel lengths (typically between 16″ and 24″) and other calibers such as .41 Magnum, .32 H&R Magnum, and even .22 Magnum.

The Crossbolt Safety

This rifle here is my personal 1894 in .357 Magnum. You may have seen it in some of our previous videos. It’s without a doubt one of my favorite guns ever. This one was made in the early 1980s.

One notable feature missing from this rifle is the cross bolt safety. That was added to all Marlin lever actions in 1983. A lot of lever action purists still really hate the cross bolt safety. I’m not sure I quite understand that, but I’ll admit it’s not my favorite safety design.

The pre-safety Marlins have a half-cock notch, so you can chamber a round, carefully lower the hammer, and now you can carry the gun in the field and it’s completely drop safe. When you want to shoot, you just cock the hammer as you bring the gun up on target. So you could argue that the cross bolt safety was an unnecessary addition. But you can always just ignore it if you don’t want to use it. You can even buy a plug to fill the hole if you want to remove the safety completely.

The Remington Era

The Marlin story took a significant turn in 2007 when the company once again changed ownership. A private equity firm known as Cerberus Capital Management bought up a number of companies in the gun industry including Remington and Marlin. These were all placed under a holding company called The Freedom Group, later renamed Remington Outdoor Company.

This ended up being a supremely bad move for all parties involved. Some of these companies had pre-existing financial problems, outstanding debt, and management issues when they were acquired. But the new ownership only made things worse. In the case of Marlin, they fired everyone who actually understood the industry and how to make guns and replaced them with cost-cutting managers with no industry experience. And to be fair, that might be over-simplifying the situation, but it’s not too far off, from what I can tell.

The most flagrant example of this mismanagement was in 2010 when the new owners shut down Marlin’s factory in Connecticut and moved manufacturing to Remington’s plants in New York and Kentucky. The Connecticut plant was not a modern, cutting edge operation. The equipment was very old with lots of retrofitting and improvised modifications. But it was a functional operation – they were making decent rifles, it just required intimate understanding of the machines and processes. This institutional knowledge was the biggest loss Marlin suffered when the factory moved and the workers stayed behind.

There was a lengthy shutdown period while Remington tried to figure out what they were doing. But when the first new Marlins rolled out, there was a massive decline in overall quality. Rough actions, visible machining marks, and various fit and finish issues were the norm, with many rifles suffering much more serious problems. Shooters started calling these guns “Remlins,” and not in a complimentary way.

After years of stumbling, Remington did eventually fix many of these problems. The last couple of years of Remington-made Marlins are generally adequate. But it was too little, too late. The dip in quality left room in the market for companies like Henry and Rossi to take advantage of the rising demand for lever actions. By 2019, the Remington Outdoor Company had much bigger problems that we don’t have time to get into today. Bankruptcy was inevitable and the various companies were broken up and sold off.

Ruger Steps In

Ruger bought Marlin in 2020 and promised to bring back the beloved lever guns. They moved manufacturing again to their own facilities and ceased production entirely until they could set everything up. That sounds like a familiar story, but Ruger knows a lot more about how to make rifles than whoever the Freedom Group put in charge in 2010.

Production resumed in late 2021 with the Marlin 1895. But the Ruger-made 1894 wasn’t released until mid-23.

Early reviews were very positive. Even the most critical longtime Marlin enthusiasts seemed to be pleased with Ruger’s early efforts. But it’s been a couple of years now. They’ve expanded the lineup. Is Ruger still doing justice to the Marlin brand?

That brings us to the model we’re looking at today – the Ruger-made 1894 Trapper. I’ve put about 800 rounds through this rifle over the last couple of months, and so far, I am very impressed.

Ruger-Made Marlin 1894 Trapper: The Basics

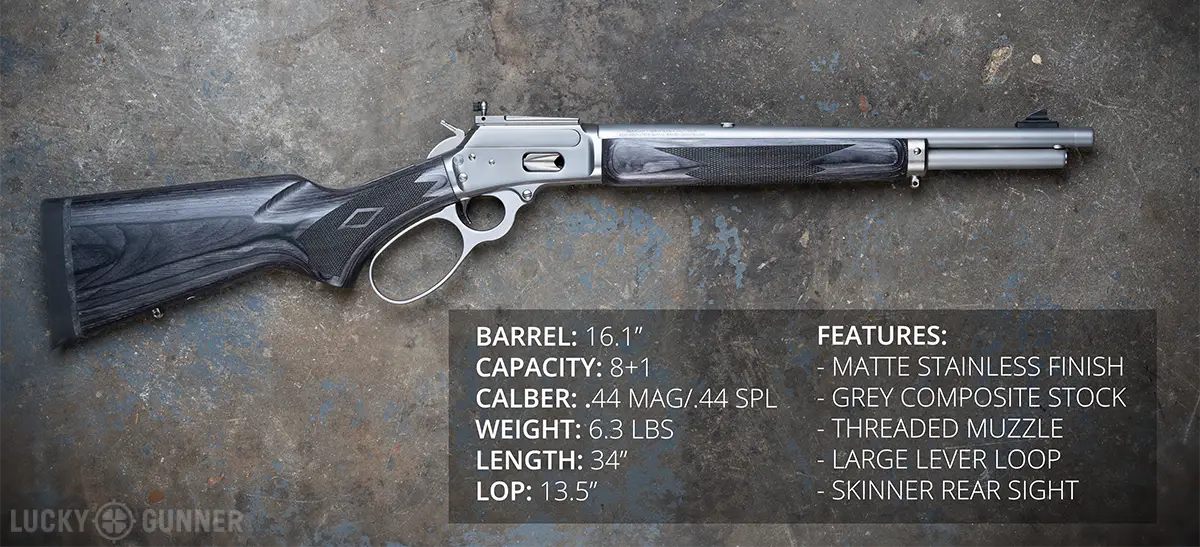

Let’s start with the specs and features. The 1894 Trapper is offered in .44 Magnum and .357 Magnum. This is the .44 Magnum version which, of course, can also fire .44 Special. It has a 16.1-inch barrel, 8+1 ammo capacity, a large loop lever, and a matte stainless steel finish. The furniture is grey laminate and the stock has a 13.5-inch length of pull. The unloaded weight is 6.3 pounds with an overall length of 34 inches.

The trigger is clean and predictable, breaking at about 4.5 pounds. It’s not a match-grade trigger, but it’s entirely appropriate for this type of rifle.

The muzzle is threaded with a subtle non-textured thread protector. So you can attach a suppressor if you want, but it doesn’t have that tactical space gun look.

The stainless finish on this particular gun is more or less flawless – no scuffs, dings, or imperfections anywhere. Even after all the handling and shooting we’ve done with it, it hardly looks used at all. I haven’t left it out in the rain or anything, but it seems like this is the kind of gun that’s going to look good for a long time without having to baby it.

The overall fit and finish shows a lot of attention to detail. The loading port is properly beveled and free of any burrs or machine marks. None of the screws in the action have worked themselves loose so far.

Sights and Accuracy

The signature feature of the Trapper models is the sights. It comes with a Skinner brand rear aperture sight, which is a nice upgrade over the barrel-mounted buckhorn rear sight you get on the standard Marlins. The barrel does have the dovetail cut for that style sight with a filler installed. So you’re not stuck with the peep sights if you want to change them in the future. You can also remove the rear sight and mount a scope or a dot optic as well.

The rear sight is adjustable for windage and elevation. It’s a large peep sight – more of a ghost ring size. Skinner does have smaller inserts available. I like the larger aperture. It’s great for snap shooting at close range, which is where these guns really shine anyway.

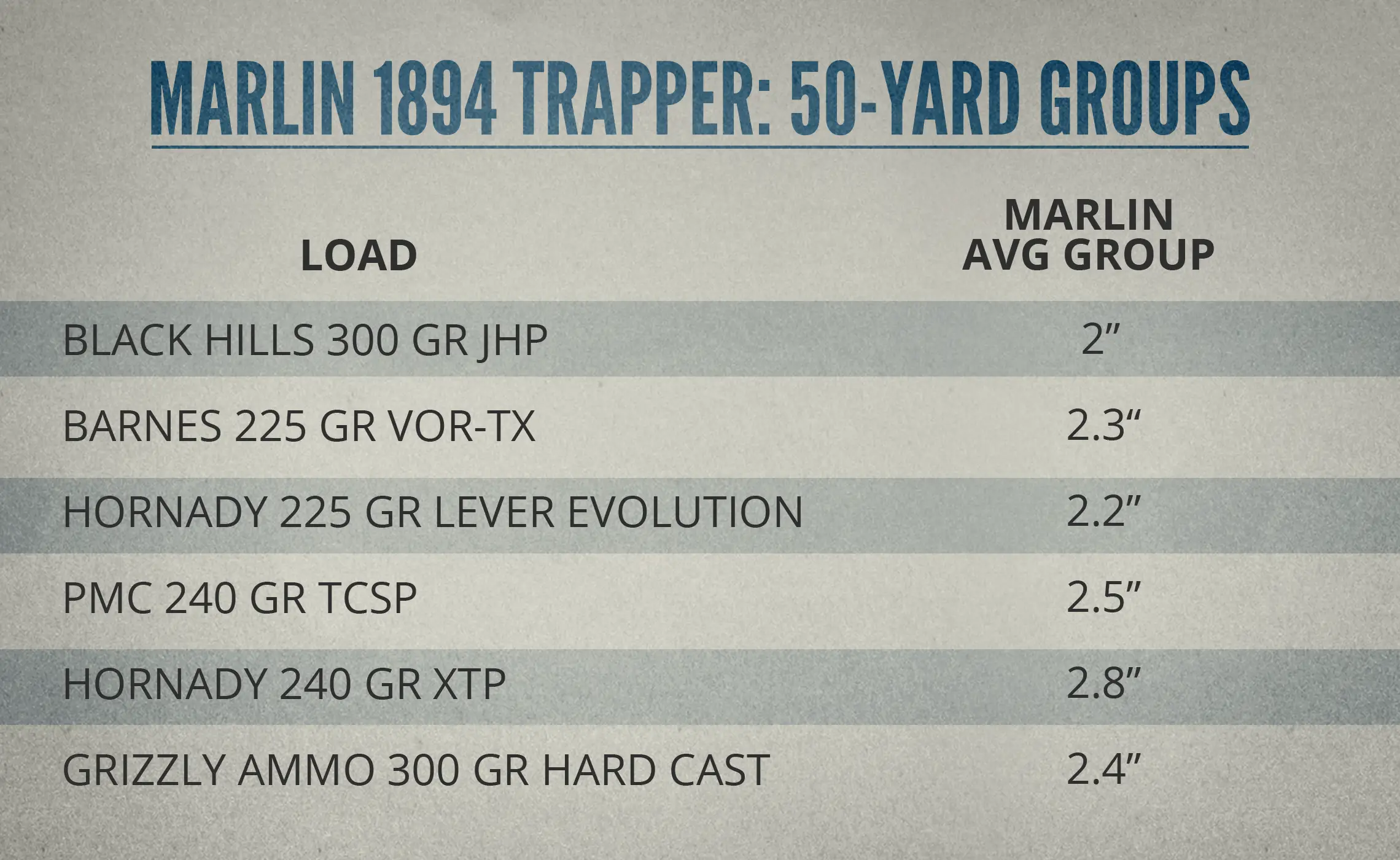

But I did mount a scope for the bench rest accuracy testing. I shot six different loads. Two five-round groups each at 50 yards. Most of them shot between 2 and 2 and a half inches. Nobody is looking for a .44 lever gun to be a precision track driver. But it’s worth noting that I’ve reviewed two other .44 Magnum lever actions in the past that were meaningfully more accurate. The Henry X Model and the Chiappa Alaskan both averaged well under 2-inches at 50 yards with the same premium hunting loads I tested in the Marlin. Both rifles shot an inch or better with at least one load.

I may have just gotten unlucky with this rifle. Or maybe I haven’t found the loads that it likes yet. I know some other people are reporting better accuracy from their Ruger-made Marlins. Practically speaking, 2 inches at 50 yards is fine for a gun like this. If nothing else, it’s predictable. There’s not much difference between loads and it’s not throwing crazy fliers or anything like that.

“Smoothness” and Reliability

But let’s talk about the action. The smoothness of the action can make or break a lever gun. To me, this is the real test of whether Ruger is doing it right. It’s something that Remington never seemed to figure out, especially with the 1894. That’s partly because of how this action was designed. A lot of pistol caliber lever actions are based on Winchester designs which are often considered inherently smoother than the Marlin 1894.

I’m no lever action expert, but based on my experience, when people talk about smoothness, they might be referring to one of three different things. The first type of smoothness is just the absence of grit. Nobody likes to run a lever that feels like there’s sand in the action. It’s like licking a paper towel. It’s just… ugh, gross. It seems like this is more of a manufacturing problem than a design issue. Any action can feel gritty or smooth in this way depending on how the parts are finished.

Ruger passes this one with flying colors. There is no grit whatsoever in this action.

The second kind of smoothness has more to do with how the lever transitions between the different stages of the action cycle. You should always run the lever with some authority when you’re actually shooting, but if I cycle through this one slowly, you can see it has several distinct stages where the resistance changes. Ideally, those transitions should feel smooth when you run the lever at full speed. It shouldn’t feel overly stiff or like it’s catching. This is where the 1894 can sometimes feel less smooth, or maybe slower than a Winchester-based action, or even other Marlin actions.

Again, Ruger has done a great job here. I don’t feel any of those transitions when I’m shooting. It’s pleasant to cycle, especially once it broke in after the first couple of hundred rounds. There might be other actions that feel a little smoother when you’re just handling them. Outside of a cowboy action match, I don’t think you’re going to notice much difference at the range.

The third type of smoothness is related to the second. How well does the gun handle different types of ammo? The bullet profile and overall length of the cartridge will sometimes determine whether you get any of those hiccups in the action. For example, with certain types of .38 Special, the lever on my 1894 will sometimes hang up at the halfway point as I’m closing it until I let it back out a little bit and then close it.

From what I understand, the .44 version of the 1894 has historically been more ammo sensitive than the other chamberings. So how did Ruger do here?

Well, I loaded the gun with 8 different loads, alternating between .44 Magnum and Special. I ran the action about as fast as I could. No problems feeding any of those rounds. I almost short-stroked the lever there at the end, but that was just me trying to go too fast. It does not like to feed the Blazer aluminum cased ammo. But to be fair, that’s not unusual at all, and the owner’s manual advises against it anyway. Other than that, it’s run everything I’ve fed it. In terms of reliability, I’d put it up against any other lever action on the market.

Value

The MSRP on the 1894 Trapper is $1,499, but actual retail prices are typically closer to $1,200. That’s a couple hundred dollars more than most 1894 variants cost at the tail end of the Remington era. But pretty much all guns cost more than they did in 2019.

Either way, the difference in overall quality more than makes up for the price disparity. Lever actions are not cheap guns to manufacture. They require more attention to detail than a budget bolt action or AR-15. And the price reflects that.

This gun was not hand picked for us. We didn’t get it from Ruger. I just went down to the store and bought one they had on the shelf. If this sample is representative of what we can expect with the new Marlins, I think the price is completely justified.

If you’re trying to decide between the .44 and .357 versions of this gun, you might want to check out the video I did a few years ago on that very topic. There’s a lot of good info in there on velocity, effective range, ballistics, and hard barrier penetration. Personally, I’d go with the .357 Magnum just because the ammo is a lot cheaper. But they’re both very fun, versatile rifles.

Guys, thanks for watching. I hope you enjoyed this one. Until next time, when you need some ammo, be sure to get it from us with lightning fast shipping at Lucky Gunner.