When last we left the biography of the .38 Special, it was the 1980s, and this cartridge was still going strong as probably the numerically most common defense cartridge among both private citizens and law enforcement despite being a good eighty years old.

The Quest for Expanding Duty Ammo

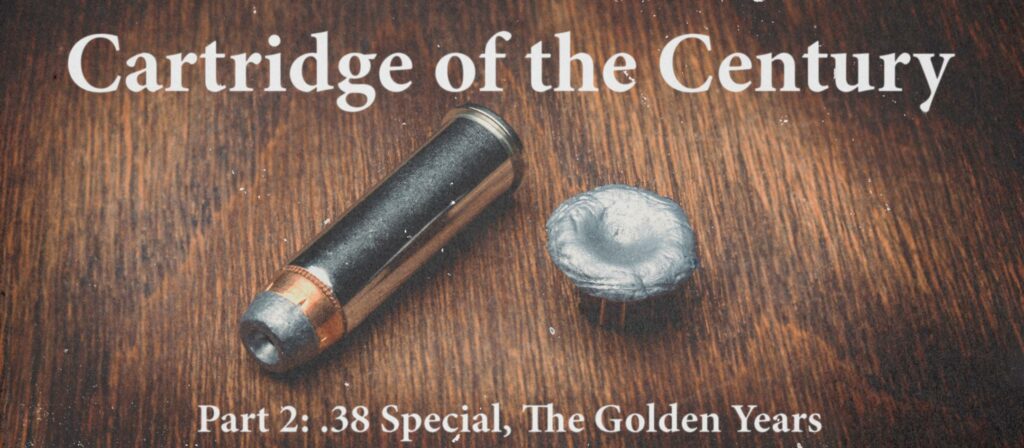

Spurred by smaller companies like Lee Jurras’s “Super Vel,” the big name players had all released high-velocity +P+ 110-grain loadings that flirted with supersonic velocities out of 4” barreled service revolvers while still avoiding the magnum stigma. The supposed problem with these hot cartridges was that most manufacturers recommended they only be fired in revolvers rated for .357 Magnum ammunition, and none of the small-frame snubbies fit that definition in that era. It wasn’t until 1999 that Smith & Wesson’s J-frames had official factory blessing to shoot +P ammunition. Winchester and Remington both wound up offering a round that met SAAMI pressure levels for +P and still gave the velocities that everyone was fixated on by the simple expedient of utilizing 95-grain jacketed hollow points. While heavy on the muzzle blast from short barrels, these were still doing close to 1,000 feet per second even from a snubby and close to supersonic from duty-size guns. This velocity made for the sort of neatly expanded Winchester Silvertip hollowpoints that look good in advertising copy. It was the desire for expansion that produced another variant of .38 Special ammunition as well. Back in the days when they were owned by Bangor Punta, Smith & Wesson had their own in-house ammo line. One of their offerings was a target .38 wadcutter that was completely coated in soft nylon. This “NyClad” bullet was touted as reducing airborne lead on indoor ranges as well as cutting down on lead buildup in the gun and the dirty, smoky bullet lubes associated with it. It didn’t take long for someone to realize that the nylon coating process could be used to coat a dead-soft semi-wadcutter hollow point and the bullet would expand, even at low velocities, far more readily than one with a copper jacket. When Smith & Wesson got out of the ammunition business, the NyClad name and process were sold to Federal, who continued production for many years thereafter. The bullet remained popular for snub-nosed revolvers and shooters who preferred to avoid the increased blast and recoil of +P ammunition.

Penetration Matters

It was around this time, in the mid 1980s, that the .38 Special cartridge had a starring role in one of the most well-known shootouts since the O.K Corral. Agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation on a rolling stakeout for a pair of bank robbers in the Miami area found their quarry and forced them off the road in a residential area.

“Attention was paid by the Bureau to the 9mm bullet that failed to reach the robber’s heart. While this is often simplified as being an issue of caliber, what the FBI focused on was adequate penetration.”

The ensuing gun battle, known these days as simply “The Miami Shootout”, featured a rifle-wielding bad guy aggressively taking the fight to the FBI agents, despite having been hit with a bullet that would have eventually been fatal; a 9mm Silvertip that penetrated his arm and laterally into his chest, stopping short of his heart. Although the robber was eventually put down by a brave agent, Ed Mireles, with 158-grain +P lead semi-wadcutter hollow point (LSWCHP) loads from his service revolver, the big takeaways from the shootout in popular law enforcement culture were twofold.

The Waning Dominance of .38 Special

Law enforcement saw a stampede away from lightweight bullets at the same time as the stampede away from revolvers. The .38 Special, which had entered the decade as the dominant law enforcement round, was on the way to becoming a niche round for backup guns. As a result of the Miami shootout, the FBI instituted a new ammunition testing protocol that required rounds to both expand and penetrate to a certain depth in ordnance gelatin after defeating a variety of barriers, including heavy clothing, drywall, sheet metal, plywood, and auto safety glass. One of the first casualties of this protocol was the classic 158-grain +P LSWCHP “FBI load” since the soft lead bullet couldn’t perform well through intermediate barriers. For waning days of the era of revolvers at the FBI, a new standard load was adopted: a 147-grain +P+ HydraShok from Federal. This jacketed hollow point was intended to duplicate the terminal ballistics of the proven LSWCHP while delivering good performance through barriers.

.38 Special in the 21st Century

The Gold Dot load was authorized or issued by several large police departments for backup gun use which is what the .38 Special has largely been relegated to in 21st Century American law enforcement. With private citizens, though, the snub-nosed revolver remains a popular primary weapon. When the Gold Dot short barrel ammo first became available, it added considerable capability to guns whose owners had previously not had a lot to choose from in the ammunition department. Given a choice between a variety of hollow points that would not expand, many had just loaded their snubbies with wadcutters for the penetration and low recoil.

“Given a choice between a variety of hollow points that would not expand, many had just loaded their snubbies with wadcutters for the penetration and low recoil.”

With the cartridge now mostly used by private citizens for personal defense in snubby revolvers, Hornady took a long look and asked themselves what was really needed by this group of end users. It was great that the new offering from Speer and some others on the market were performing well in law enforcement-oriented testing, but how much barrier performance does the average private citizen need? By abandoning the goal of defeating things like auto windshields and concentrating on performance against bare or lightly clothed gelatin, Hornady was able to develop a 90-grain variant of their FTX Critical Defense bullet that was doing close to a thousand feet-per-second out of some snub-nosed revolvers while still operating at standard .38 Special SAAMI pressures. By not having to resort to +P pressure, recoil and blast was kept down and the bullets were marketed as Critical Defense Lite. The packaging features prominent use of pink, and the flex-tip insert in the FTX bullet is also a pink elastomer. It doesn’t take an Ivy League MBA to tell that these were, and are, marketed at the growing number of women electing to carry a self-defense firearm. Detractors point out that by going with such a lightweight projectile, the .38 Special is effectively transformed into a gun the size of a pocket 9mm with the ballistics of a .380 ACP. Proponents counter that a round that works from the shooter’s gun and that they are willing to practice with beats a magnum that they aren’t. So here we are, coming up on 120 years after the birth of the .38 Special cartridge. It still enjoys popularity in some pistol games and, while it’s no longer the premier personal protection round in the US, it’s still serving in that capacity and with capabilities undreamed of when they decided to add a few more grains of black powder to the old service cartridge all those years ago.

I hope you guys have enjoyed Tam’s two-part history of the .38 Special cartridge. I know I sure learned a lot. For more wheel gun goodness, take a look at our latest ballistic gelatin test and see how different .38 Special and .357 Magnum loads compare! –Chris