A few weeks ago, we looked at whether red dot sights are a good idea for a concealed carry pistol. Lots of our followers expressed skepticism — not just for red dot sights, but for any kind of sights being useful in a real world defensive encounter. Is there a specific distance where we should plan to shoot “instinctively” rather than rely on the sights? Is sighted fire even possible considering the close range and quick reaction times required in most scenarios? Should we be practicing a combination of sighted fire and point shooting? We can’t give you any definitive answers, but we can offer some strong opinions!

Details in the video below, or scroll down to read the full transcript.

Hey everybody, Chris Baker here from LuckyGunner.com. Today we are continuing our exploration of some of the myths and realities of armed confrontations. Last week, we tried to figure out at what distance most justified defensive shootings take place. The typical range seems to be roughly three to five — maybe three to seven yards. Today, we are now going to look at whether we need to use the sights on our handgun to hit a threat at that range. And considering the speed and chaos involved in these encounters, is using the sights even feasible to begin with?

Of course, not every encounter is typical. There have been incidents that took place at ranges closer than three yards and some that happened as far out as 25 yards and more. Some of you asked how a defensive shooting could possibly be justified beyond 20 feet or so. There are a lot of reasons that could be the case. For example, if you’re being shot at or even just threatened with a firearm from 50 feet away, it might be reasonable to shoot back, especially if there’s no feasible way to take cover or retreat. But most of the so-called “long range” self-defense cases I’m aware of were justified because the person was defending the life of another victim — very often a family member or friend — who was in much closer proximity to the attacker. In those types of situations, having some method of accurately aiming your pistol is a dire necessity.

But those situations are rare. Most people have limited training time and resources, and they want to prepare for the most likely scenarios first. Since the majority of defensive shootings take place at roughly 10 to 20 feet, that’s what we’re focusing on today.

Point Shooting Versus Sighted Fire

What we’re really getting into here is the age-old debate between point shooting and sighted fire. Or you might call it instinctive shooting versus aiming. There are several problems with how this debate usually goes, starting with the fact that nobody can seem to agree on what point shooting even means. Today, I’m going to use that term very broadly to refer to any shooting done without explicitly referencing iron sights, an optic, or laser sight. I’m not saying that’s necessarily the correct definition, it’s just the one I’m using for the sake of this discussion.

Another issue with the point shooting debate is that we are often presented with a false dichotomy. It’s either always use the sights because that’s the only way to get hits or always point shoot because in real life, nobody can use their sights.

But all we have to do is listen to feedback from gunfight survivors to find that these two extremes are not a reflection of reality. Most people don’t recall ever seeing their sights, but oftentimes, they still get effective hits and stop the threat. Some people do vividly recall seeing a sight picture and that tends to get good results, too. A lot of people don’t remember one way or the other. Both methods can be effective depending on the person and the circumstances.

One more nuance that often gets lost when we talk about sighted fire versus point shooting is that using the sights is not an all or nothing thing. A difficult target at long range might call for a perfect textbook sight picture. When the target is extremely close, we don’t need the sights at all. In between, there is a grey area where we might see an imperfect sight picture that we use as just a very coarse reference — what we call a flash sight picture. I did a video on the flash sight picture a couple of years ago with some helpful animations that you might want to check out if you’re unfamiliar with that concept.

There are no strict rules for whether or how much you should rely on the sights at any given distance. And distance isn’t the only determining factor, it’s just the most obvious one. We might have to deal with a moving target, bad lighting conditions, obstacles, or bystanders. There are a number of factors that determine the difficulty of the shot. The harder the shot is, the more we need to rely on the sights or some kind of aiming reference.

Two Point Shooting Demos

I’m about to demonstrate how I personally use iron sights on a pistol at various distances. This is not meant to represent what everyone can do or should do. Pistol sights and vision work a little differently for everyone. Even among shooters who are far more skilled than I am, I don’t think I’ve heard any two of them describe in exactly the same way what they see when they’re shooting. My goal here is just to illustrate that there’s a lot of grey area between “always use a hard front sight focus” and “always point shoot.”

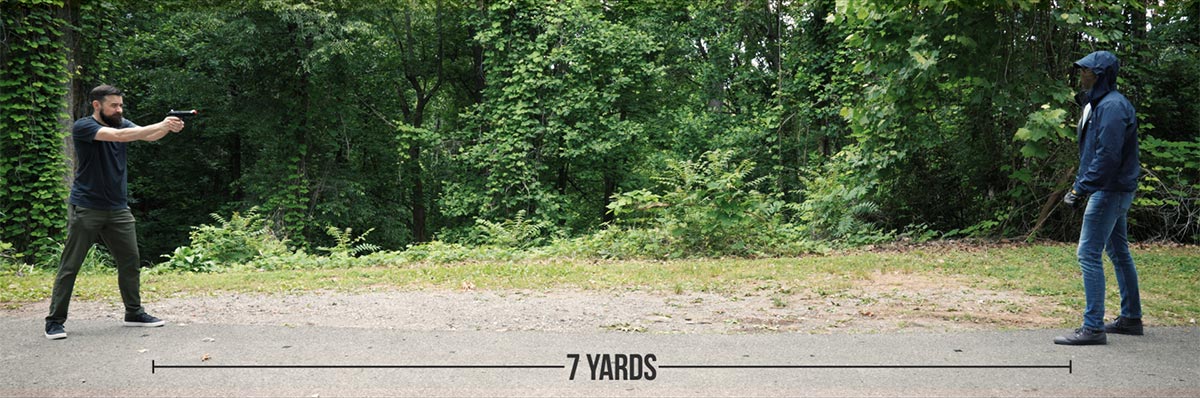

I actually filmed this two different ways. The first was with an airsoft pistol with the sights covered up and a training partner. Kenneth here volunteered to be my bad guy and let me shoot at him. I wanted to find out at what range I could no longer guarantee good hits without sights.

This camera perspective gives us a nice visual reference for just how much space would be between me and an attacker at these various distances. The difference of just a few feet can be far more significant than we sometimes realize.

Unfortunately, the airsoft pellets didn’t really show up on camera with our kudzu jungle backdrop there. So to give you a better idea of where my hits are going, I also did a similar exercise at the range with a paper target.

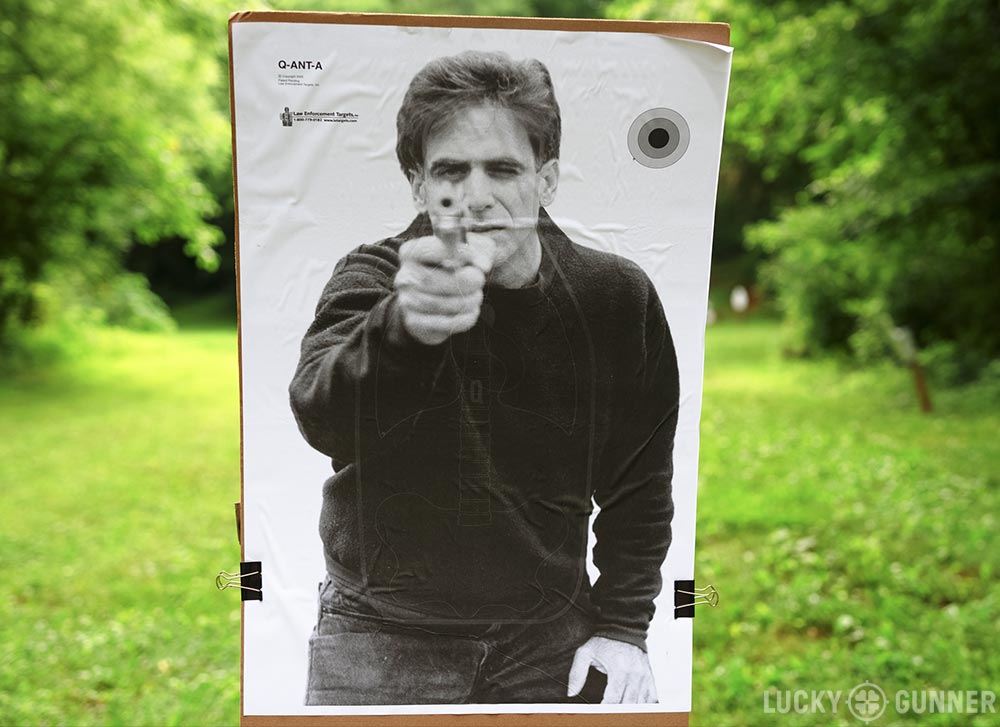

I used a photographic target with an anatomical overlay because I really wanted to see the difference between a good fight-stopping hit and a not so good peripheral hit. In hindsight, it’s not an especially accurate anatomical overlay, but it’s close enough for what we’re doing today.

At each distance, I fired sets of three shots on the timer starting from a high ready position. I did four sets of three with the sights covered and four sets of three without the sights covered.

Back to our airsoft exercise, Kenneth is starting out at true contact distance: in this case, about two feet away. He’s a pretty tall guy — 6’3”. I’m 5’9”.

At this range, it may not even be wise to draw the gun at all if it’s not already out of the holster. He can easily reach out and grab me or my gun. So I definitely don’t want to extend the gun, let alone try to use the sights. That’s how my gun becomes our gun and that’s a really bad place to be.

Defensive shooting at extreme close range is a completely separate discipline all on its own. It is way outside my lane, so I’m not going much into that today. Suffice it to say, if you have to shoot from contact distance, using your sights is the least of your concerns. For more on that topic, I suggest looking up some videos with Craig Douglas or Cecil Burch on close contact and retention shooting.

Okay, now let’s back it up to about two yards — six feet. At this distance, it’s probably safe to bring my gun to full extension at eye level. It kind of depends on what he’s doing and whether he’s closing that distance. I might need to pull the gun back in if he gets too close. Either way, I don’t need sights to get a good high center chest hit.

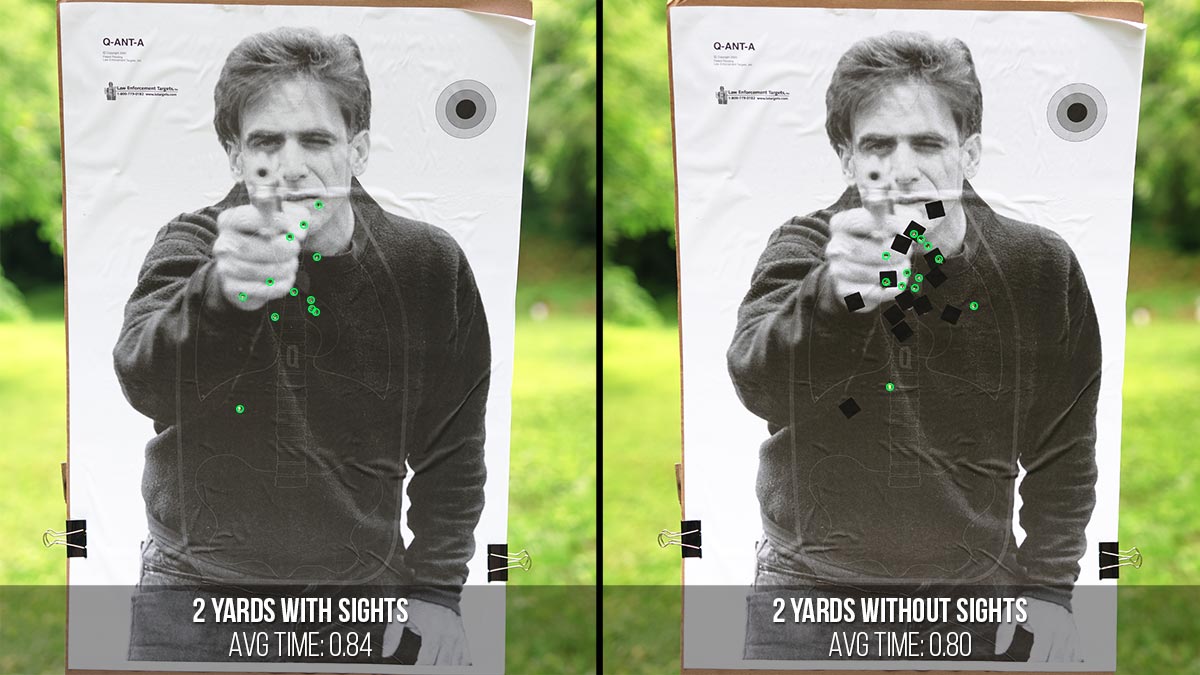

On my paper target at two yards, it doesn’t make any difference whether or not my sights are covered. I’m not looking at them. I can actually fire with the gun at chest level from here if I really need to.

Trigger control still matters at this distance. You can see I yanked a couple of shots really low. But that has nothing to do with the sights.

For the most part, I’m getting good hits. Some of them are a little higher than what we might consider ideal. But there’s still a lot of important anatomy up there. Hitting the gun hand is also pretty effective.

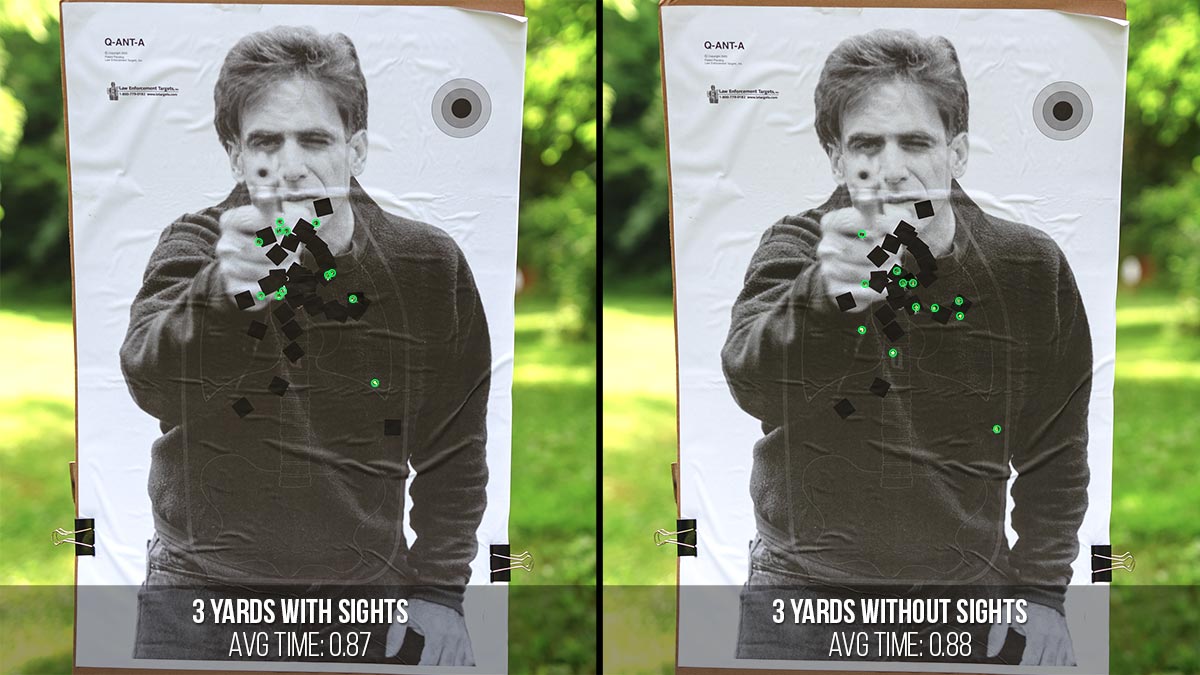

Now let’s go to nine feet — the proverbial three yards. Here, I can definitely go to full extension without the risk of handing him my pistol. I’m still not paying any attention to the sights at this point.

Again, you absolutely can miss completely at nine feet with bad trigger work. You can see here on both of my paper targets, I yanked a shot low and to the right.

Overall, there’s not a significant difference in the quality of my hits here for sights covered versus uncovered. Visually, I’m vaguely aware of the orientation of the slide, which some would say is a form of aiming. Even this close up, I do think it’s easier to get hits if the gun is positioned between my eyes and the thing I’m looking at. But this still feels pretty much like what I would call point shooting.

Once we move out from three yards to five yards, my ability to get accurate hits without the sights starts to decline. I’m not missing him, but some of the hits are borderline.

On the paper targets, things still look mostly good on both sides. Unsighted, I’m getting more peripheral hits than I would like. I’ve got one way up here on the ear that was almost a complete miss. I’ve got another three in the shoulder that are not ideal for stopping an attacker.

At five yards, I definitely have a sight picture. It’s a pretty rough one, but I am using the sights. Sometimes, my eyes will be focused on the target at this distance and the sights will be fuzzy. Usually, I prefer a front sight focus at five yards but that doesn’t always happen. That’s one of those things that varies a lot from one shooter to the next.

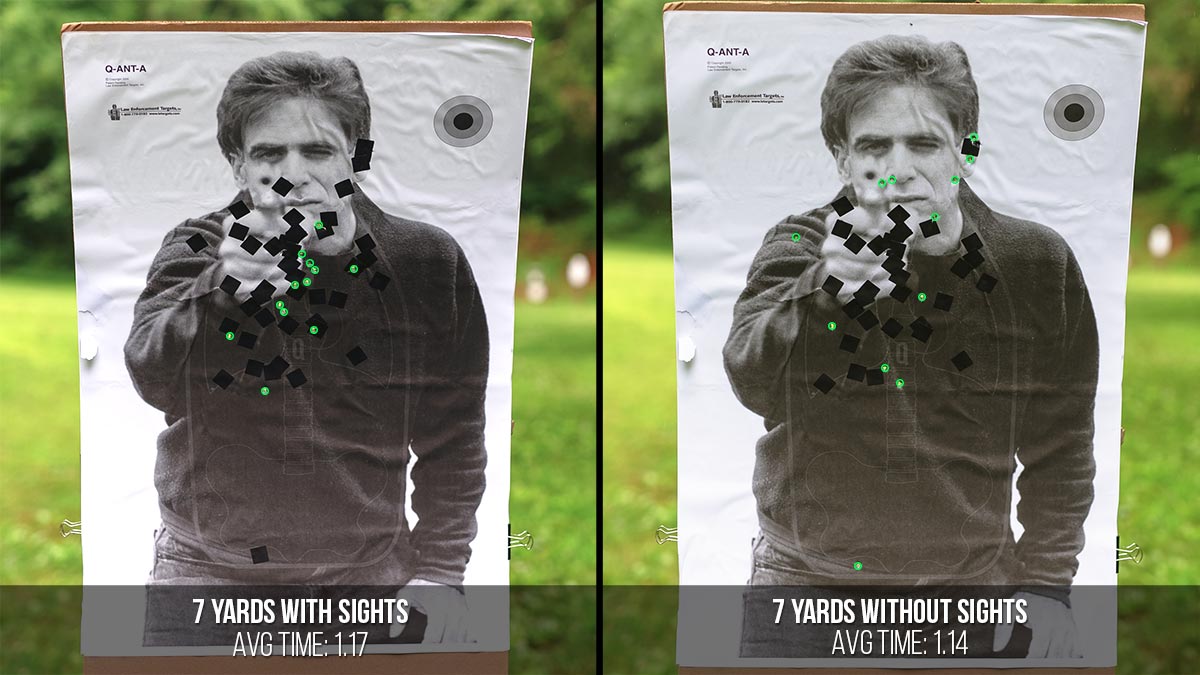

Without sights, the decline continues at seven yards. I’m hitting him, but sometimes those hits are in the shoulder or down in the gut. If he were to start moving around at this range, I’d have a much harder time hitting him at all.

On my seven yard paper targets, we can really see the disparity between sighted and unsighted. Without the sights, I technically managed to keep all the hits on the bad guy, but just barely. About half of those are peripheral hits.

The thing to really pay attention to here is the time difference. It didn’t take me any longer to use the sights than to point shoot, but the accuracy was much better. Most of the old point shooting techniques were developed back when iron sights on handguns were small and very difficult to see. With modern, high visibility iron sights, there’s really no reason I have to rely on point shooting at seven yards.

The real paradox of the point shooting versus sighted fire debate is that learning to quickly acquire a sight picture essentially trains you to point the gun at the target. If you practice sighted fire the correct way, you will automatically get pretty good at point shooting at the kind of ranges where a lot of people claim you will not have time to see the sights.

If I was unable to see my sights for some reason, or my red dot and my backup irons have both somehow failed, I can just do what I’ve always done in practice and I’ll usually still get some pretty good hits. Practicing with sights doesn’t mean I suddenly forget how to shoot if I don’t see them. On the other hand, if you primarily practice point shooting, it does not make you better at sighted fire. If a situation calls for a higher level of precision, you will have limited your ability to get that precision on demand.

So there’s a place for point shooting. You might want to try it on occasion to see if you can do it. It’s what I would teach a novice if I thought they were realistically never going to practice again. But if pistol shooting is a skill you intend to improve, most of your time should probably be spent on sighted fire.

Guys, I hope you have found this to be a helpful spin on the point shooting debate. If so, hit that like button, be sure to subscribe to our channel, and buy some ammo from LuckyGunner.com.