Is .22 Magnum a good caliber for personal protection? Maybe. .22 Mag has been around for nearly 60 years, but for most of that time, it’s been a cartridge primarily used for hunting small game and plinking. But in recent years, there has been a rising interest in using lightweight .22 Mag revolvers for concealed carry. In Part 8 of our Pocket Pistol Series, I’m considering the pros and cons of relying on a .22 Mag when your life may depend on it.

Details in the video below, or keep scrolling to read the full transcript.

Since we started our deep dive into the world of pocket pistols and other small caliber handguns, I have received endless requests to talk about the .22 Magnum. Well, .22 Magnum fans, your day has arrived. And for the rest of you who have been following this series waiting to see if I’ll cover your favorite mouse gun caliber, fear not. I will get to it. I’ve got stuff planned for .32 ACP, all the various .32 revolver calibers, .380 ACP, and if you comrades are really nice, I might even throw in something about 9mm Makarov just for kicks. And I’m still planning to review different carry methods and holsters and pocket-pistol specific drills and shooting tips.

If you’re already sick of hearing me talk about pocket pistols, that’s okay. We can still be friends. I plan on taking plenty of breaks along the way to look at some completely unrelated topics before we get to the end of this series.

.22 Magnum, or more officially, .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire, made its debut in the 1960s as a cartridge for hunting varmints and small game. Even though it’s most effective when fired from a rifle, revolvers chambered for .22 Magnum have been around as long as the cartridge itself. These revolvers have been used for hunting, pest control, and target shooting, but more recently, they usually take the form of concealable lightweight snub nose revolvers intended for personal protection.

There is also one semi-auto .22 Magnum in current production: the Kel-Tec PMR-30. Its claim to fame is a magazine with an impressive 30-round capacity. But its viability as a serious self-defense tool is questionable. Since it’s basically a full size pistol anyway, it doesn’t fit into our pocket pistol series so I’ll save my critique of that one for another day.

A modern .22 Mag snubby typically gives you six or seven shots in the same size package that would normally hold five rounds of .38 Special or eight rounds of .22 LR. That makes the .22 Magnum an interesting compromise between those other two cartridges. But is it the best of both worlds or is it the worst?

Out of a 2-inch barrel, .22 Magnum makes a lot of noise, but the actual felt recoil is barely more than a .22 LR. So it’s a lot easier to control effectively than a .38, which is especially important for a lightweight revolver. But another trait the .22 Mag shares with .22 LR is the rimfire primer and along with that comes more frequent ignition failures. On average, the quality of .22 Magnum ammunition actually seems to be higher than that of .22 LR, but failures to fire due to light primer strikes are still common. With a revolver, that’s not necessarily the end of the world. If the round doesn’t go off, you just press the trigger again and fire the next round. But obviously, if you’re relying on this gun for self-defense, the last thing you want is to get a click when you expect a bang.

This Ruger LCR I’ve been using fails to fire about once every 25 rounds. Now, that’s not normal for an LCR, and I need to send the gun to Ruger and let them take a look at it. At the same time, it’s not a surprising issue to run into and something you usually don’t have to worry about with a centerfire model.

To help prevent these ignition problems, the gun makers use heavier springs in the rimfire revolvers, so the triggers are much stiffer than the centerfires. I talked about this issue when I covered the .22 LR revolvers and it’s the same with .22 Magnums. Most of the centerfire LCRs I’ve measured have triggers between eight and ten pounds. My trigger pull gauge maxes out at 12 pounds, but I’d estimate this .22 Magnum to be around 14 or 15 pounds, which is heavy, even by rimfire standards.

With most of these guns, it’s possible to swap out the factory springs for lighter springs. Every revolver is a little different and sometimes the lighter springs work just fine, but for other guns, it might cause reliability problems. Ultimately, you can get a .22 Magnum revolver that runs very reliably, but it might take some luck, or some experimentation with different brands of ammo, or a trip back to the factory. And you still shouldn’t expect it to be as reliable as a .38 or any other centerfire version of the same model.

With .22 LR it can be easier to overlook the reliability issues because you can enjoy all the benefits of dirt cheap ammo. But that’s not quite the case with .22 Magnum. Based on current ammo prices, the average cost per round of .22 Magnum is about four times higher than .22 LR. It’s roughly on par with the cost of 9mm. The good news is that .22 Magnum is still more affordable than .38 Special, which is usually priced about 60% higher still. You’re probably not going to make a habit of burning through 500-round bulk packs of .22 Magnum in a single afternoon, but compared to anything other than .22 LR, the cost is not bad at all.

So really, it all comes down to ballistics. Is .22 Magnum significantly more effective than .22 LR? .22 Magnum is known for being far more capable than you might expect such a small cartridge to be. But that legendary reputation is primarily built around hunting with .22 Magnum rifles. A shorter barrel takes away a lot of that punch.

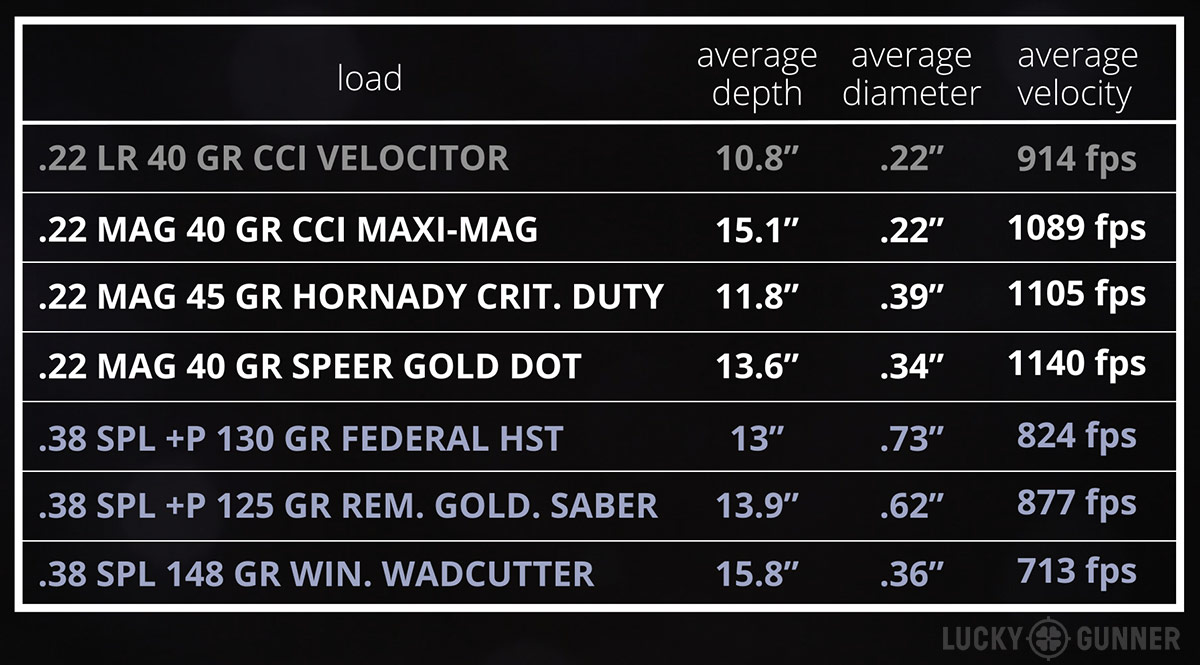

For example, the label on this box of 40-grain CCI Maxi-Mag hollow points claims a velocity of 1875 feet per second. I have no doubt it can do that out of a rifle barrel, but with a 1 ⅞-inch snub nose, it averages only 1089 feet per second — that is 42% slower. So, we can’t expect rifle performance out of a .22 Mag snubby, but let’s look at how it compares to a .22 LR. The CCI Velocitor is one of the faster .22 LR loads out there. It also has a 40-grain bullet, and out of a snub nose, I clocked it at 914 feet per second. So in this case, the magnum is faster by 175 feet per second.

I will be doing some more extensive velocity and ballistic testing with these calibers in the future — probably after we’re done with everything else we want to cover in the pocket pistol series. For now, I did another quick informal ballistic gel test with a few .22 Magnum loads to get an idea of what effect this bump in velocity might have on terminal performance.

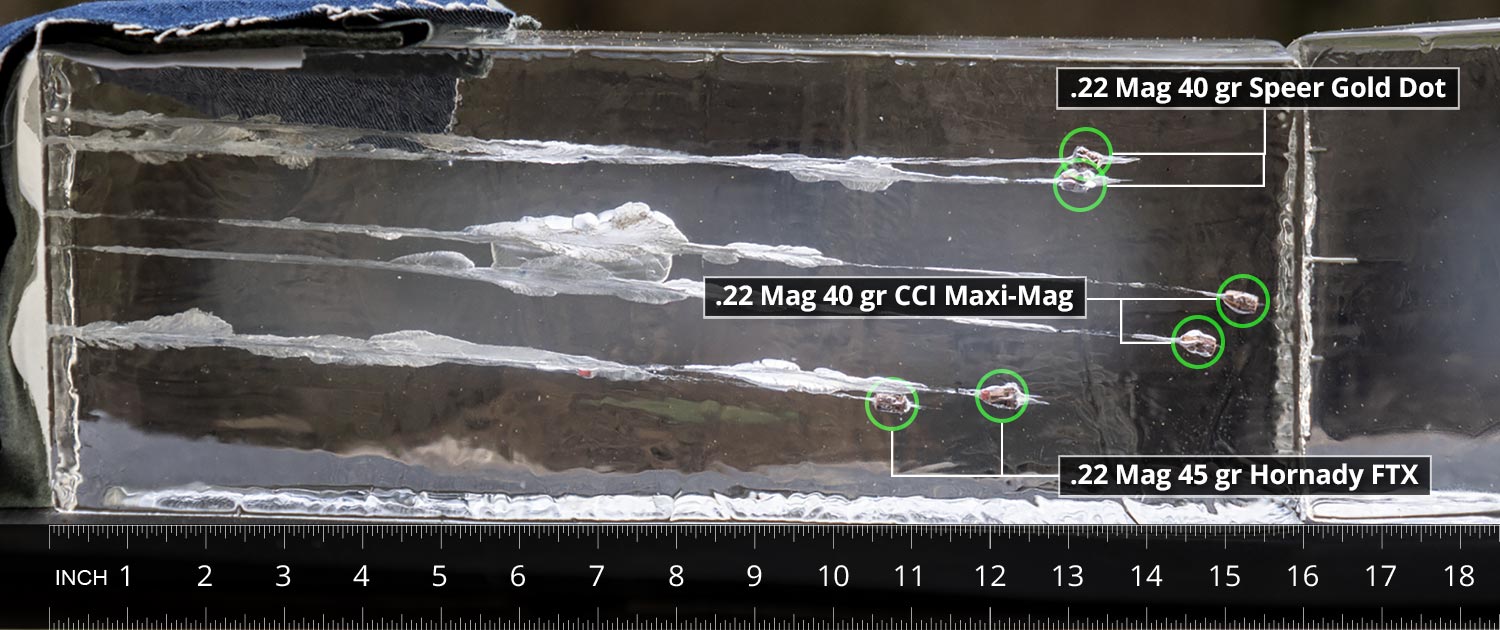

Starting with two rounds of the CCI Maxi-Mag, we got a penetration depth right around 15 inches. There was no expansion, which is not a surprise since these bullets were designed for much higher velocities. Looking back at our gel test of the .22 LR CCI Velocitor from a few weeks ago, you can see that load only averaged around 11 inches of penetration. So a 19% increase in velocity got us a 40% increase in penetration depth, putting our .22 Magnum bullets well within the ideal 12-18” range.

I also tested a couple of .22 Magnum loads from Hornady and Speer that are specifically designed for self-defense with short barrels. The Hornady Critical Defense box actually lists velocities for a 24-inch rifle and a 1 ⅞-inch revolver. It says here to expect 1000 feet per second, but my chronograph measured it a little faster than that at 1105. In the gel test, the penetration depth was around 11 to 12 inches and we did see a little bit of expansion. The two rounds of Speer Gold Dot I tested were moving along at 1140 feet per second. They ended up right in between the other two loads at 13.6 inches and also had some nice expansion.

So we’ve got what looks to be some pretty decent performance here. The penetration depths look very similar to what we were getting with some of our .38 Special loads from our big test a while back. Of course, with the .38s, you’ve got the potential for a lot more expansion, and even if it doesn’t expand, the bullets are much heavier and probably less likely to deflect if they hit bone. But the little 40-grain .22 Magnum seems to be punching way above its weight, especially when you consider the almost non-existent recoil.

I’ll admit that in the past, I’ve been pretty quick to dismiss .22 Magnum because it does lose so much velocity in a short barrel, so why not just use a .22 LR? But looking at these velocities and what these loads are doing in gel has me second guessing that opinion.

If you are considering a .22 Magnum snub nose for concealed carry, I would strongly suggest sticking with either a Smith & Wesson J-frame or a Ruger LCR. I know I mentioned some potential problems you can run into with these guns, but on average, I think you’ve got a much better chance of getting a decent revolver from either of those companies than any of the alternatives.

A few weeks ago, I did a detailed comparison of the J-frames and the LCRs. They are very similar in a lot of ways and both of them are solid designs. With the .22 Magnum models, the main difference is the ammo capacity. The Smiths hold seven rounds and the Rugers only hold six. The standard .22 Magnum LCR is a double action only model like this one. It weighs 15.1 ounces, which is actually a little bit heavier than the .38 Special version. The LCRx has an exposed hammer for a single action capability, and there’s also an LCRx with a 3-inch barrel. That one is pretty interesting because I bet that extra inch of barrel could squeeze quite a bit more velocity out of those .22 Magnums.

From Smith & Wesson, you have two options: the 351 C and the 351 PD. Both have an aluminum frame with an aluminum cylinder making them among the lightest Smith & Wesson revolvers ever made at 11.5 and 11.2 ounces respectively. The double action only 351 C is essentially the .22 Magnum version of the 43 C that I talked about in part 7 of this series. It’s got the same XS front sight and U-notch rear and synthetic grips. The 351 PD has a hammer spur, a fiber optic front sight, and wood grips.

And that’s the end.