A lot of people have asked why I prefer my self-defense revolvers to be double action only. My initial reason was that the hammer spur would often catch on my clothing when drawing from an appendix carry position. A popular method of avoiding this problem is to place the thumb of the shooting hand over the hammer during the drawstroke. However, not only does that require maintaining separate drawstroke techniques for revolvers and semi-autos, it also prevents achieving a full firing grip on the gun while it’s still in the holster, which I consider to be a key component of a fast and consistent presentation. So for me, double action only is the clear way to go.

But not everyone has experienced the same issues with the hammer snagging on clothing, and some self-defense revolvers are intended for home protection use only, and are never carried. In those cases, wouldn’t it be better to retain the single action feature on the off-chance one has to take that difficult precision shot in a life or death encounter? If the only consideration was making the gun easier to shoot, I would say “yes.” However, when I take into account the potential safety concerns involved with introducing an uncommonly light, short trigger pull into a situation of extreme stress, I think the wiser path is to avoid the use of the single action capability of defensive revolvers entirely.

I know many will disagree with this assessment, and that’s perfectly understandable, but I believe this is an area where the hard won experience of past generations can be very enlightening — there is much we can learn from the history of double action use in the law enforcement world. Watch the video below for a summary of that history and the implications for the armed citizen, or keep reading for the unabridged version.

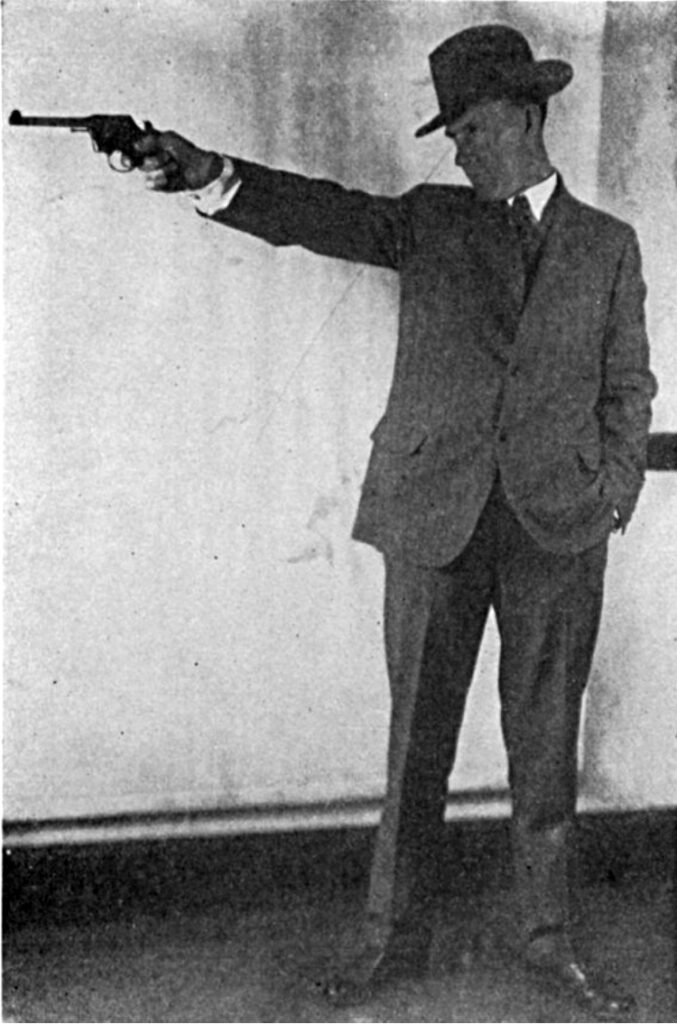

When double action revolvers first came into popular use in the early 1900s, they were really thought of as single actions with a bonus double action feature that would only be used in dire emergencies. The assumption was, if you actually had time to bring the gun up to eye level and use the sights, you also had time to thumb cock the hammer.

Of course, today we know it’s possible to use the sights to get quick and accurate hits, even with a double action trigger stroke. Manually thumb-cocking the hammer for the lighter single action shot is no longer considered acceptable in the defensive firearms training world. So why is it that most revolvers made today still have the single action capability? We have plenty of double action only small frame models to choose from, but most people assume that they are useless beyond arm’s reach, and for revolvers larger than pocket size, double action only is almost unheard of as a factory option. But history has shown us that a single action trigger is not only unnecessary on a defensive revolver, it’s actually a liability. Today, the hammer spur is nothing more than a relic of early 20th century police training doctrine that was already outdated 80 years ago.

Double Action: A Slow Start

Well after the introduction of the double action revolver, there were plenty of well-known gunfighters still making good use of single actions. Progress in shooting techniques was, to some degree, limited by the equipment they had to work with. For example, take a look at the Smith & Wesson 1905 Hand Ejector pictured below. If you were to try to aim this revolver with the hammer down, all you would see is the back of the hammer spur. You can’t actually see the sights at all until the gun is cocked. So it makes perfect sense that even an experienced shooter from that time would pick up one of these revolvers and assume that double action and accurate shooting are mutually exclusive.

Even models that didn’t have this issue were typically equipped with minuscule sights that were difficult to see in any kind of hurry, and the double action trigger pull itself was often excessively stiff and uneven. The stocks (more commonly called “grips” today) were also designed with single action shooting in mind and it would be years before grips appeared that positioned the hand to get better leverage for a double action trigger press.

More importantly, the police training of the pre-WWII era emphasized one-handed single action as the default technique. F. H. Fitzgerald, later a vocal proponent of double action, advised in 1920 in The Colt’s Police Revolver Handbook that double action shooting should be reserved for targets no more than 15 to 25 feet away. By some standards of that period, 25 feet would have been considered really stretching the limits of double action. The Manual of Police Revolver Instruction written by R. M. Bair for the Pennsylvania Highway Patrol in 1932 says that “The revolver should only be fired [double action] in emergency, as when the hammer cannot be cocked by the thumb or when in very close proximity to the adversary, such as a hand-to-hand scuffle. At greater distances firing double action will cause muzzle wobble, flinching and wild shots. It is impossible to keep the sights in proper alignment when the target is at greater distances.”

From the FBI to Weaver

Around this same period in the 1930s, there were a few radical innovators in military and law enforcement training circles who really started to promote the merits of double action revolver shooting. Guys like William Fairbairn, Rex Applegate, Delf A. “Jelly” Bryce, and others demonstrated that their point shooting techniques were quicker and more effective than the old style of single action target shooting. They would get down in a low crouch and fire double action with the revolver in one hand held at hip level. The FBI hired Bryce in the 30s to create a firearms training program, and it is thanks to his influence that the FBI became one of the first major law enforcement entities to embrace point shooting. The excerpts below are from a 1956 FBI Training Film demonstrating the technique that I recently heard colorfully described as “pop a squat, take a shot.”

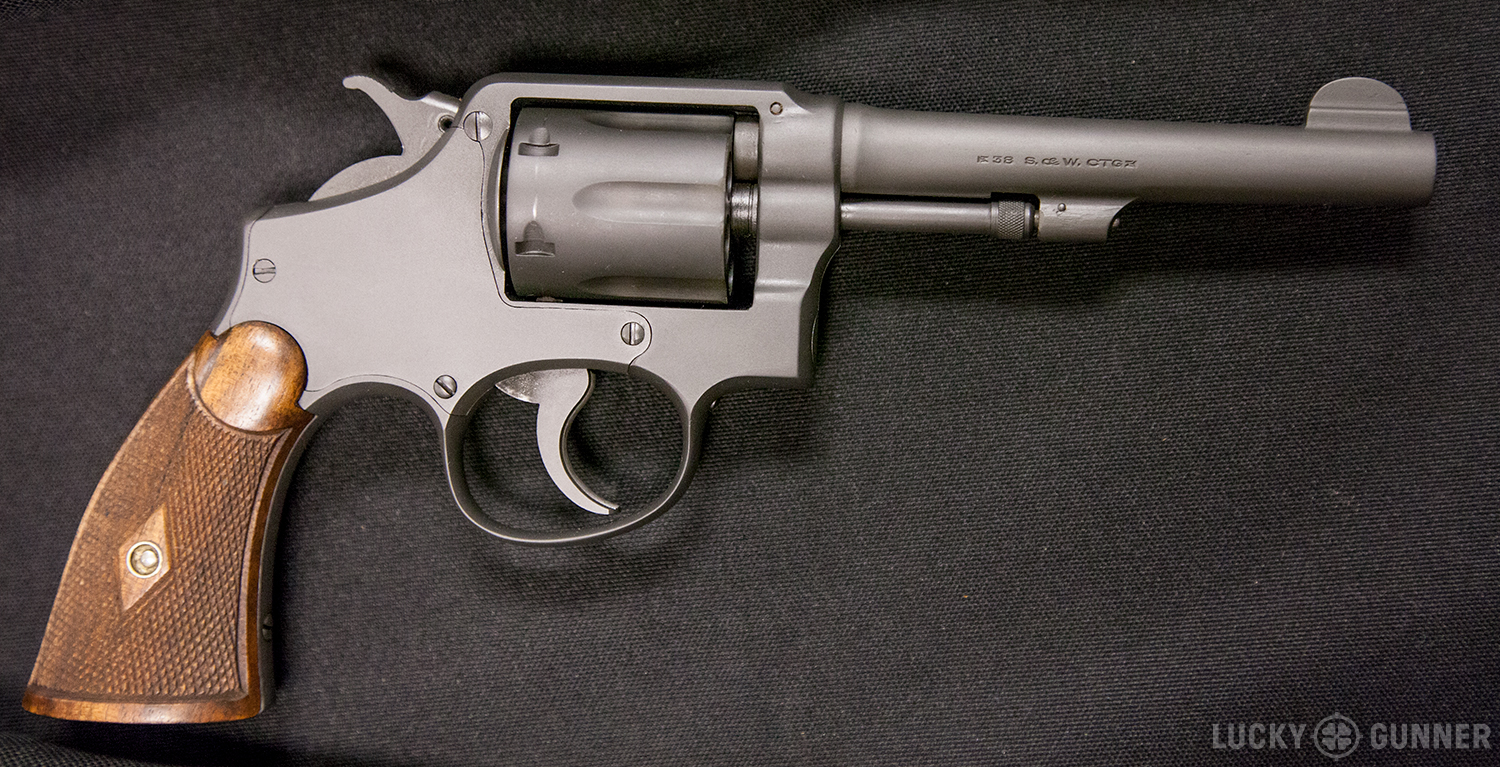

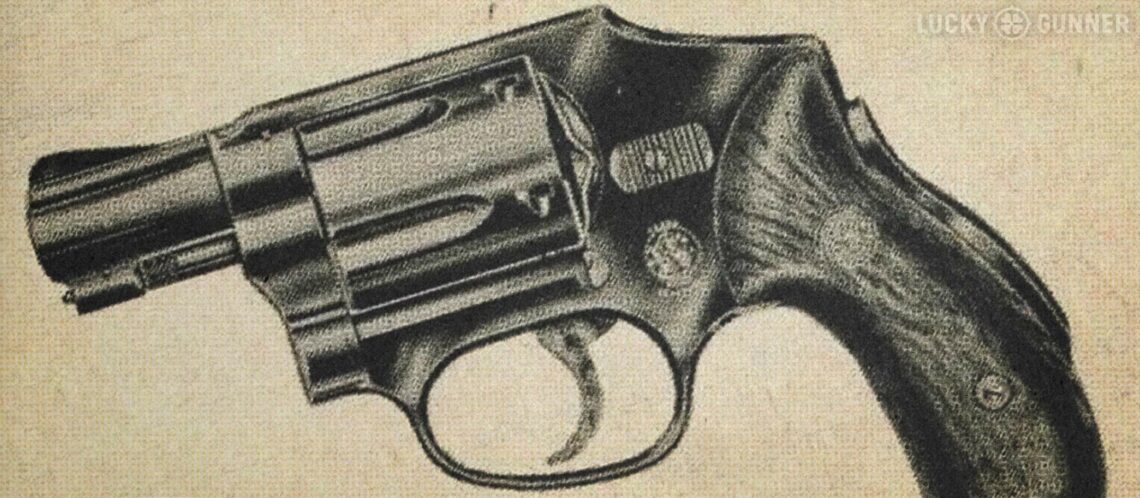

Even though the FBI encouraged double action point shooting, it definitely didn’t catch on everywhere. But by the 1950s, double action techniques had received enough validation in actual street encounters that some law enforcement training started to change and you can even see evidence of that in certain guns that were being used around that time. For instance, at the suggestion of Rex Applegate, in 1952 Smith & Wesson introduced the Centennial — a double action only small-frame revolver with an internal hammer. It wasn’t their first so-called hammerless design, but the snag-free profile made it one of their best sellers, and the derivatives of that model are still popular today.

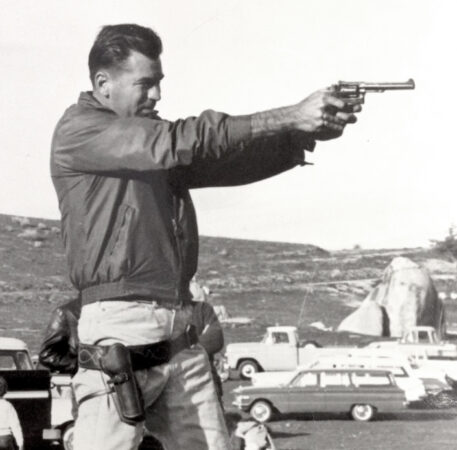

The next big leap forward in shooting techniques came from Jack Weaver in the late 50s and early 60s. Today, he’s best known for having the Weaver stance named after him, but his bigger contribution was demonstrating that a two handed grip with the gun at eye level was more effective than shooting from the hip. He used this technique in 1959 to win Col. Jeff Cooper’s Big Bear Leather Slap quick draw event, while all of his fellow competitors were point shooting from the hip. Weaver found he was able to acquire a flash sight picture with the large target sights on his Smith & Wesson K-38 and squeeze off an accurate double action shot more reliably than attempting the same precision without using the sights. Weaver’s technique was adopted by Jeff Cooper, who developed further it into the Modern Technique of the Pistol. The Modern Technique, in turn, is what led to most of the techniques we use today, both in competition and in defensive firearms training.

But in the 60s, these guys represented the absolute cutting edge of combat shooting. Police firearms training in general was very slow to change. In most departments, the guys who would have been considered serious shooters were honing their skills by competing in traditional bullseye matches and other forms of competition with generous time limits. The easiest way to excel in these matches was to fire the revolver single action. Firearms instructors were often recruited from the top competitors in these matches, so police training continued to be biased toward single action shooting into the mid-1900s and beyond.

At the same time, that era produced some highly successful gunfighters who were also competitive shooters. The most well known is probably Jim Cirillo from the NYPD Stakeout Squad. He won a lot of gunfights and a lot of bullseye matches, but he always fired his revolver double action, even at 50 yards.

The Hazard of Single Action

Double action shooting was repeatedly shown to be effective in the field, but what probably led police departments to eventually move away from single action was the liability issue. Single action and nervous cops in tense situations do not mix. This reality was recognized as early as 1930 by J. H. Fitzgerald (the same one who wrote the 1920 shooting manual for Colt) in the book Shooting where he wrote, “The double action has its advantages for many occasions where the officer must carry his revolver ready for instant use, as in entering a house or room in which he has every reason to believe a criminal is hiding. If he should enter the house with his revolver cocked, a loud noise, as the slamming of a door or the throwing of some article, may cause him to fire a shot because less than one-eighth of an inch pull will release the hammer. On the other hand, if the revolver is carried with the finger near the trigger ready for double-action shooting five-eighths of an inch is required to fire the shot and for a quick shot it is not necessary to have the finger on the trigger, but just outside ready to slip inside the guard.”

This is sound advice coming from an experienced police shooting instructor in 1930, but many police departments didn’t change their training and policies to de-emphasize single action shooting until the 1970s and 80s. In the meantime, a lot of suspects and innocent bystanders were needlessly injured or killed as a result of officers trying to use cocked revolvers as people management tools.

Lessons for the Armed Citizen

So what can we learn from all of this and how is it relevant for the legally armed citizen today? First of all, I think history shows us that the single action feature of a double action revolver is just not necessary. Once double action techniques came into popular use, the single action capability did not provide a major advantage in police-involved shootings, and the same thing can be said for the kind of close-range encounters that account for the vast majority of armed citizen defensive shootings. Statistically speaking, 15 yards could be considered extreme long range for a justifiable shooting, and modern revolvers can still be effectively fired double action at that distance with a very modest amount of practice.

There may be a case to be made for single action for someone with a disability or diminished hand strength who can’t actually manipulate a double action trigger. In many of those situations, however, a brief coaching session or some grips that fit better can get them running that double action just fine. If the shooter still struggles with double action and has to rely on shooting single action, they should be instructed in how to safely decock the revolver, and warned about the potential for an accidental or negligent discharge that can result from thumbing the hammer back when it is not absolutely necessary to fire.

Like I mentioned at the start, for a concealed carry revolver, the hammer spur presents multiple opportunities to foul the draw stroke, which is arguably the most important part of the armed response. 20th century cops were typically carrying service size revolvers openly in holsters or concealed by a stiff suit jacket or a heavy overcoat. The hammerless snub nose revolvers were carried in pockets. The hammer spur on your double action revolver was not designed with modern concealed carry in mind, which is often with the gun inside the waistband and close to the body covered by lightweight shirt or jacket that is easily snagged by the “fish hook” shape of the hammer.

But even if the potential for snagging doesn’t worry you, as long as you’ve got that ability to fire single action, there’s a good chance you’re going to be tempted to practice that way when you’re at the range. Getting the hang of the double action trigger takes some discipline because it can be challenging and maybe even discouraging at first. But when you rely on single action at the range, all you’re doing is programming your subconscious brain to think that if you really need to hit your target, you have to thumb that hammer first.

We tend to operate on auto-pilot under extreme stress, so if you practice that way and you ever have to respond to a potential threat, you may end up with a cocked revolver in your hand without ever making the deliberate decision to cock it. Your potential threat is, more likely than not going to turn out to be a false alarm or a situation that doesn’t require you to fire the gun. So now you have to manually decock the gun while you’re all amped up on adrenaline, presenting a whole new opportunity for an unintentional discharge.

There is also the legal issue to consider. I’m no expert in this area, but it’s a topic that Massad Ayoob has written about extensively over the years. The possibility exists that you could become involved in a justifiable shooting, and instead of trying to convince a jury that your actions were intentional but unjustified, an over-eager prosecutor could use that light single action trigger to allege that you fired accidentally, and then get a conviction for manslaughter or negligent homicide. It sounds far fetched, but it’s happened more than once, and it’s definitely worth taking into account.

For most people, I think the best thing to do is either buy a double action only revolver or have a gunsmith remove the hammer spur and convert the gun to double action only. I know it’s kind of funny looking without a hammer, but you’ll get over it. If you do keep that single action capability at least do your very best to ignore it because putting a hole where there should not be one is a lot more likely than picking off a terrorist at 50 yards.

Special thanks to Darryl Bolke and Tom Givens for helping out with some of the research for this article.

“However, not only does that require maintaining separate drawstroke

techniques for revolvers and semi-autos, it also prevents achieving a

full firing grip on the gun while it’s still in the holster, which I

consider to be a key component of a fast and consistent presentation.”

Great article with some good points. The quote above though seems a bit contradictory. Separate draw strokes implies the subject is changing out EDCs. This is not a big deal so long as you’re “keeping it in the family”, so to speak. Going from a striker-fired DAO only semi-auto to say a 1911 would require some relearning – extra training time that could be better spent with the original weapon facilitating your “fast and consistent presentation”. The two are similar enough in function though that the lost time would be minimal.

Taking it a step further, going from any semi-auto to a revolver is even more of a change. You’re not only splitting your training time, you’re also splitting your attention when a situation does arise that requires you to be focused like you’ve never been focused before. If you’re really worried about a fast and consistent presentation, train with one gun/platform only.

It’s always bothered me a bit when trainers advocate changing EDCs (and I’m not saying you’re advocating it). If the perfect training scenario for a fast and consistent presentation is keeping the same exact gun and learning it exclusively, any change from that same gun is costing you time, at the very least. At worst, you could have a brain fart and try to fire your 1911 without releasing the safety, for example, or reach for a magazine to reload your Python. Do you really want to see how well your brain works under stress while you’re under THAT stress?

I would not suggest that anyone arbitrarily change their carry pistol, and I agree that when changes are made, it’s best to stick to the same action type. I was only speaking for myself and I’m in a somewhat unique position of frequently testing and shooting different guns for research and product evaluations. However, there are plenty of other legitimate reasons someone may want to practice and remain competent with both revolvers and semi-autos, and using one type of draw stroke for both would be beneficial.

Agreed. As a gunsmith, I shoot a lot of different firearms over time. That doesn’t necessarily qualify me for critiquing draw strokes and whatnot, but it does seem to make sense to stick with the same platform if you want to be proficient.

FYI: Here is J.H. FitzGerald demonstrating a suspiciously familiar stance back when Jack Weaver was less than 2 years old. Fitz’s stance is more of a Cooper-style Weaver than even Jack Weaver’s own stance.

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/84ab9d5fae42fd2fdfc85d713694670b700fa599d66fc870a418c0f804f175af.jpg

Yes, that photo is in Fitz’s 1930 book “Shooting” in the chapter on two handed shooting. He suggests officers use a two handed teacup style grip in order to steady the gun if they need to take a shot after running. Weaver’s innovation was using two-handed sighted fire in a close range “quick draw” context. Even that had probably been attempted by someone else at some point in time, but having Cooper there to witness it and subsequently train thousands of people to do likewise is what makes it history.

It is important to note that in the early years, the “Weaver Stance” was little more than shorthand for a two-handed stance. Note the variation in this collage from 1965. I find it interesting how close Elden Carl’s stance is to the Modern Isosceles, including the use of both thumbs pointing forward.

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/0cb3d8e9ebb25602c518dc489b53f2adb940b8969bda81da67e693dbf88d1db6.jpg

I’m kind of surprised that you didn’t mention Ed McGivern, the patron saint of DA revolver speed shooters. Some of McGivern’s records would stand for over a half century until the 1980s when beaten by exhibition shooter Joe Walsh, a sheriff’s deputy from New Jersey. Others would wait for Jerry Miculek. https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/5cfffeabe267a4932706016f4f4eae4c19cc2de834cdbe1a55b1f6d96784daca.jpg

FYI: The S&W Centennial was not terribly popular when it was originally released. Back in the 1970s, S&W historian Roy Jinks noted that its sales rapidly faded once the Bodyguard models were released with their semi-shrouded hammers. Sales were bad enough that the Model 40 and 42 were dropped from the catalog in 1974. Once articles by Wiley Clapp and other gunwriters turned the Centennial into a hipster’s gun, S&W reintroduced the model in 1989.

I’ll have to take your word for it regarding the early lukewarm commercial reception. Regardless, I would say that convincing a major revolver manufacturer to produce a hammerless snub nose aimed at LEO use was, at the time, a big win for double action only as a viable concept.

When it comes to revolvers I own and carry a S&W 642 for every reason that you described. I use to carry a S&W 649 or 637, but practice and experience taught me that a DA only is as accurate and has less liability than a SA/DA revolver …thanks for the post

Chris, I really look forward to your very informative discussions featuring DA or DA/SA handguns; due to the extra margin of safety you have highlighted. Here in Florida where T shirts and cargo shorts are year-round; I like a small pocket holstered pistol for EDC. I recently traded my S&W J-frame revolver for a Sig 290rs semi-auto DA-only to gain another 4 rounds to 8+1 in 9mm; without compromising micro pocket size. Yes, it has a long smooth pull and long reset, but in so many ways it ‘feels’ like my J-frame including the ‘restrike’ capability. Really accurate, comes right back on target, and has great night-sights that are so much better than a J-frame. My Home Defense double-stack CZ’s with DA/SA have the same long-smooth 1st shot, so it’s straightforward going from one to the other. With DA, I don’t feel the need for a redundant manual safety.

I *only* carry DA/SA, and CZ is my #1 weapon choice to fill that need.

Andy, I couldn’t agree more about CZ’s. They’re superb. Their Tactical version decocker models like SP-01, P-01, PCR, and RAMI BD are IMHO the very best DA/SA semi-auto pistols available. But I do respect that others might prefer a different DA platform.

Great write up. I’m not willing to modify my revolvers, but I totally agree with you on double action only for self defense. I find the hardest thing to do is to force double action only practice at the range. Once you get into the mindset; things go easier from there. I also notice a lot of other readers/comments from people who carry J-frame revolvers. While I don’t own one, I have shot many. My EDC is a 3 inch model 65. Not as easy to carry as a J frame; but I truly feel the K frame is the perfect balance between size, capacity, trigger “feel” etc. I will say I would like to try shooting an SP-101 in both barrel lengths (2.5 & 3 inch), as I wouldn’t be opposed to “bobbing” the hammer on one of these as a potential EDC. The only issue is loosing the sixth chamber – but that’s another matter!

In addition, you might want to check out Bob Nichols’ 1950 book “The Secrets of Double-Action Shooting.”

I like DAO on semi autos as well as revolvers. I own a fair amount of handguns, but all in all, my favorites are of the DAO variety. My S&W 64-3 is an extension of my arm. My S&W 4586 is a very manageable, no nonsense beast. The Sig P250 I have is another keeper.

The S&W M&P .45, DAO, I bought is less than appealing to me. Had it been a hammer gun like the P250, I’d like it a lot better. Why it was marketed as a DAO trigger is beyond me, it’s like no other DA trigger I’ve tried. It’s just that these lightweight staple gun triggers, do not appeal to me at all.

My newest addition is a stainless Charter Arms Bulldog snubby, DAO, in 44 SPL. It has a nice handful of grip, can make five large holes and offers up little in the way for an up close BG to grab on to. It’s Crimson Trace laser grips are currently sighted in at 50′. For a 20 ounce handgun, it can pack a helluva wallop.

As far as the “DA is safer than SA,” I’d say, Maybe, maybe not. In the 70s, the old Police Marksman magazine ran an article about a study of the startle reflex. The methodology was this: An officer was given a (safe) K-frame revolver and told to advance on a simulated subject at the other end of a simulated alley. At a certain point, a person hidden from the officer’s view reached out and squeezed the back of the officer’s thigh. The idea was to see if the startle reflex could cause the officer to fire the revolver double-action. Percentage of officers who fired? 100%.

I’m also aware of an officer who shot himself in the thigh when he slipped on gravel with a revolver in his hand (hammer down, DA).

That said . . .

In 1986 Miami PD Officer Luis Alvarez shot and killed a convicted felon who was drawing a gun with the intention of shooting him in a Miami video arcade. As a result of the ensuing riot, Dade County State Attorney Janet Reno charged Officer Alvarez with murder. During the trial, the prosecuting ASA falsely claimed that Officer Alvarez had cocked his Model 64 and accidentally shot and killed the offender. (This was after several other spurious theories were shown to be lies.) After Officer Alvarez was acquitted, Miami PD altered all their issue revolvers to DAO.

I think it’s a wise move to only carry DAO revolvers (and DAO autos). I think it does prevent SOME negligent discharges, my above caution notwithstanding. In addition, it shuts off an avenue of false accusation.