I think some fans of the .357 Sig cartridge choose that caliber purely because they like being the underdog. Or maybe they’re just gun hipsters. But in either case, their obscurity complaints are pretty small time compared to the followers of the mighty .38 Super.

The “other” .38 has been around since 1929 (kind of… we’ll get to that), but has never managed to become popular. Yet, it won’t completely die off, either. Most of the major ammo manufacturers still make limited quantities of .38 Super, and a handful of gun makers trickle out a small supply of pistols chambered for the caliber–mostly 1911s. So just how has this cartridge managed to hang on to relevance for so long, while also showing little to no hope of ever becoming a major contender in the Great Caliber Wars™? To answer this, of course, we must go back to the beginning…

Which came first, the bullet or the gun?

Just like any cartridge that’s been around for nearly a century, the history of .38 Super tells an interesting story if you look beyond the surface. Despite the similar name, .38 Super has nothing to do with .38 Special, or any other revolver cartridge. Its origins are in the .38 ACP cartridge, also called .38 Automatic, .38 Military, and about a dozen other names. The .38 ACP was another invention of John Moses Browning, designed especially for his Colt M1900 pistol. The initial loadings were pretty hot, but it became apparent that the M1900 was not stout enough to handle the high pressures, so they dialed it down a bit.

A standard .38 ACP load will send a 130 grain bullet at about 1040 fps; more punch than the .38 special loadings of the day, but a bit shy of the 9mm. The Colt M1900 and its variants were never picked up by the U.S. Military, who instead opted for the M1911 in .45 ACP. The smaller cartridge saw modest civilian sales for a couple of decades, but never quite took off.

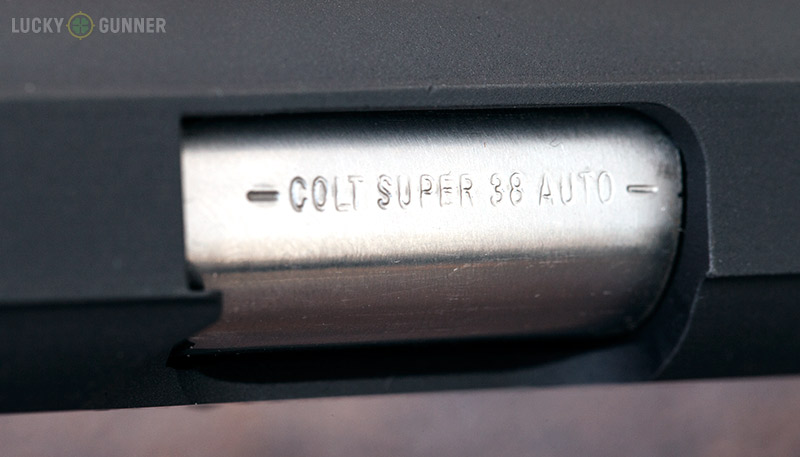

There is some debate over what happened next. In 1929, Colt introduced a new version of their M1911 pistol, called the Colt “Super .38” Automatic (they were really into quotation marks back then). Conventional gun lore has held that the .38 Super cartridge was released in 1929, and was little more than a hot .38 ACP loaded to its original velocities and designed specifically for the new Colt pistol. However, there is some evidence (including samples of Colt’s print advertising from the period) that “Super .38” was merely the name of Colt’s new pistol, not a new cartridge. Colt had intended their for new 1911 to use the more anemic .38 ACP ammo that already existed at the time.

It wasn’t until the pistol had been on the market for a few years that users discovered the 1911 design was capable of handling higher pressure loads than were currently being produced at the time. Ammo makers started selling these beefed up .38 ACP rounds, and to prevent customers from damaging their older .38 ACP pistols, they labeled the new loads after the gun for which they were intended; the Colt Super .38 Automatic.

To further distinguish between the two loads, .38 Super was re-named .38 Super +P in 1974. Today, the US authority on ammo standards, SAAMI, lists “.38 Automatic” and “.38 Super +P” as two completely separate calibers, even though they share identical case dimensions.

.38 Not So Super

For the time, .38 Super was pretty special. Okay, poor choice of words. It was powerful, at least moreso than most other handgun calibers of the early 1900s. In the first few decades of the 20th century, your choice of handguns was mostly limited to big, heavy, slow moving bullets like the .45 ACP, or small slow moving bullets like the original standard pressure .38 Special. The .38 Super was one of the first handgun cartridges that relied on velocity, rather than size, to get results.

A .45 ACP will work against vulnerable, squishy targets like the enemies of the US military, but it’s not known for its penetrating power. A 130 grain bullet from a .38 Super travels at over 1300 fps, and could penetrate the ballistic vests and car bodies of the 1930s. You might think a cartridge like that would have been a dream come true for law enforcement stuck in the arms race of the violent depression/prohibition-era gang violence. And it might have been, had the .38 Super not been completely overshadowed by the arrival of .357 magnum in 1934.

Forget the fact that a 1911 in .38 Super holds four more rounds than a six shooter (9-round mags, plus the chamber). And who cares if it has less recoil and is easier to reload? The .357 was supposed to be a man-stopper of mythological proportions. Like the .38 Super, the .357 magnum could lob a bullet at 1300 fps. Only it could do that with 180 grains instead of just 130. The magnum was a huge ballistic leap forward, and much more attractive to an American law enforcement culture that would not be ready to embrace automatic pistols for another half century.

So cops kept their wheel guns for another few decades, some switching to the new .357 magnum, but most sticking with their .38 specials. WWII hit, and Colt shifted into full-time war production. It seemed like there was no place for the .38 Super, and the cartridge nearly slipped into extinction.

The Gamer Guns

Okay, not complete extinction. The .38 Super actually made it big in Mexico and other Latin American countries where governments restrict ownership of “military” calibers like 9mm and .45 ACP. But by the 1980s in the United States, the .38 Super was little more than a footnote in gun design history, with minimal widespread exposure and a small handful of die-hard fans. And then the the “gamers” found it.

The early days of the very first formal action pistol competition, IPSC, were full of experimentation and discovery, both in terms of technique and equipment. The original concept of IPSC was built around using guns suitable for self defense, so one of the early rules was a required “power factor” for all ammunition.

The power factor rule basically issues a stiff scoring penalty to participants using ammo that doesn’t meet a certain power standard, measured as a combination of bullet velocity and bullet weight. The idea was to prevent competitors from gaming the system by shooting weaker calibers to get the speed advantage of low recoil.

In those days, pretty much everyone in the upper divisions of IPSC shot .45 ACP 1911 pistols, which easily met the power factor requirement using factory ammo. Looking for any advantage within these limitations, IPSC shooters started experimenting with different hand loads and calibers. They eventually discovered that .38 Super +P loads would not only meet the required power factor, but they held two more rounds in the magazine than .45s, and when outfitted with a muzzle brake, recoil could be significantly reduced compared to a standard 1911.

These “race guns” in .38 Super swept over the competition world, and eventually became popular among other serious handgun enthusiasts who weren’t necessarily shooting for score. But again, timing was not on the side of the .38 Super. The 80s and 90s were the era of the “wondernine”. The new high-capacity 9mm pistols from Glock, Sig, Beretta, and S&W left .38 Super in the dust as civilians and law enforcement alike again overlooked the more obscure cartridge.

.38 Super Today

Even in the competition world, .38 Super isn’t quite as dominant today as it once was, but there is still a strong following. With the advancements in ballistics technology, there are now plenty of caliber options that fill the gap once covered by the .38 Super, so it’s unlikely to catch any additional traction as a self-defense caliber. The cartridge still has decent ballistics, and there are a few companies loading modern hollow points in .38 Super, so it’ll still work for those who insist on using it as a serious load for protection, but options are limited.

As a competition gun, .38 Super has made the jump to double stack, and there are a few high-capacity 1911-style pistols available in the caliber. There can be issues with this combination, however, so a few variants of the .38 Super load have been developed to address the challenges of feeding the cartridge in a double stack magazine. At least one company makes a .38 Super that’s not based on the 1911 at all; the Witness Elite Match Tanfoglio from European American Arms. But for the most part, the .38 Super remains a cartridge married to the 1911 design, and from the looks of things, will probably remain a cartridge that manages to survive in obscurity.

Nicely written and very informative. Good work!

Need a 38 SA

been using a 38 super for decades … my favorite ….. still

Nicely written and very informative. Good work!

interesting news//glad to hear about these facts.

Need a 38 SA

been using a 38 super for decades … my favorite ….. still

interesting news//glad to hear about these facts.

I love the 0,38 Super. Everything I could want in a pistol and cartridge .Been carrying one for 3+decades .

I love the 0,38 Super. Everything I could want in a pistol and cartridge .Been carrying one for 3+decades .

Own a Taurus PT1911 in 38. super and it's a blast to shoot but I have never about it as a self defense gun. I would like to see ballistic gel testing.

Own a Taurus PT1911 in 38. super and it’s a blast to shoot but I have never about it as a self defense gun. I would like to see ballistic gel testing.

I have shot the 38 super a few times and found it to be extremely accurate round even at 25 yards. It shoots better than my eyes can see. But then again I really like the 10mm and the 357 sig also.

I didn't not know this cartridge existed until now.

(In response to your opening sentence, my first hand gun purchase was a Glock 31 in .357 Sig. I made my decision based largely on the ballistic info of the cartridge and I placed little importance on the availability and cost of ammo, otherwise I may have made a difference choice. 😛 lol)

Perhaps the .38 Super would get a larger following/chambering, if it was called the 9MM Magnum.

I have shot the 38 super a few times and found it to be extremely accurate round even at 25 yards. It shoots better than my eyes can see. But then again I really like the 10mm and the 357 sig also.

I didn’t not know this cartridge existed until now.

(In response to your opening sentence, my first hand gun purchase was a Glock 31 in .357 Sig. I made my decision based largely on the ballistic info of the cartridge and I placed little importance on the availability and cost of ammo, otherwise I may have made a difference choice. 😛 lol)

Perhaps the .38 Super would get a larger following/chambering, if it was called the 9MM Magnum.

Why?

38 super is as accurate and powerful !!! sadly is not on any shelf, only on line, I got some from LUCKY GUNNER.

You said it best….I have a 357 Mag revolver so I would rather shoot mag ammo out of it for self defense. That being said I have quite a bit of 38 special for target practice. I carry my 9mm or 45 for stopping power.

38 super is as accurate and powerful !!! sadly is not on any shelf, only on line, I got some from LUCKY GUNNER.

You said it best….I have a 357 Mag revolver so I would rather shoot mag ammo out of it for self defense. That being said I have quite a bit of 38 special for target practice. I carry my 9mm or 45 for stopping power.

I have carried 38supers since the 1970s. My current carry gun is a Dan Wesson Guardian in 38 super.

I have carried 38supers since the 1970s. My current carry gun is a Dan Wesson Guardian in 38 super.

Got a Lwt TALO Colt Commander and would like a Guardian in 38 SUPER.

Is this for automatics only? Can I use this in a Ruger GP100 38/357?

I love my 38 super. It will punch right through a car door and keep going. Very accurate with very little drop for ranges of 75yds.

How does a 38 Special +P compare to a 38 Super. I regularly carry S&W 626 with 38 Spl +P Critical Defense loads and am curious as to how they stack up against the 38 Super.

Is this for automatics only? Can I use this in a Ruger GP100 38/357?

You’re scaring me! Yes, autos only. No, can’t use it in a 38/357 handgun or rifle.

38 Super case diameter is .384…38/357 case diameter is .379. 38 Super is a 9mm, .355 or .356 bullet. 38/357 uses “.357” bullets: .359 if lead or .358 if jacketed. Modern 38 Super guns headspace on the case mouth…38/357 headspaces on the rim.

I love my 38 super. It will punch right through a car door and keep going. Very accurate with very little drop for ranges of 75yds.

How does a 38 Special +P compare to a 38 Super. I regularly carry S&W 638 with 38 Spl +P Critical Defense loads and am curious as to how they stack up against the 38 Super.

38 Special +p 125 JHP Silver Tip V=945fps E=247 Ft Lbs, (4″ Vent Bl) < 38 Super +P 125 JHP Silver Tip V=1240fps E=427 Ft-Lbs (5"Bl)

if you find a post ww1 luger ad when the company was looking for US sales, it clearly states 125 grain 1250 fps from a 4 inch barrel. (no P+) everything is being seriously down loaded these days. another interesting point take the same bullet and the same powder charge and a 9mm outperforms the 38 super. NRA article late 1970s or 1980

Looks like you are comparing guns, 44/38. I still stand by my above numbers. He is overloading the cartridge and this is not a normal 38 Spl load. A 357 Mag with a 170 SWC (#358429) 13.5 gr 2400, V=1242fps, Pres=41,100cup. I believe the load noted would not be fun in a S&W Mod 60,357 let alone a Colt Detective Special or a S&W J frame. I like my Ruger SP101 3″ 357 Mag, but not with the load noted. Over and out.

Not to be too snarky, but when I was in the U.S. Army they made it plain that “over and out” was a Hollywood phrase. It is either “over” (meaning the recipient is expected to respond) or it is “out” = same as good bye. They pounded that into us as strongly as the old “gun” vs. “rifle” mantra. However, I like what you had to say. Hope you’ll forgive my little comment.

You are absolutely correct. The 38 Super is a flat shooting and accurate round. It power falls neatly between 9MM and .357. Originally, in the late 20-early 30’s the chambers were not, head spaced correctly and there were accuracy problems. In addition, this cartridge was used in the Thompson submachine gun. The table below indicates the Power of the cartridges relative to the super. I have loaded and successfully competed with this cartridge for many years and it is fun to shoot off a 1911 platform. Further, in a pinch you can use 9MM, which feeds and ejects just fine and is reasonably accurate.

9mm Luger 115 FMJ 1190 362 137 86.71%

38 Super+P 130 FMJ 1215 426 158 100.00%

357 Sig 125 JHP 1350 506 169 106.96%

40 S&W 180 FMJ 1000 400 180 113.92%

DVC

L-626

Stan Olsen

You are absolutely correct. The 38 Super is a flat shooting and accurate round. It power falls neatly between 9MM and .357. Originally, in the late 20-early 30’s the chambers were not, head spaced correctly and there were accuracy problems. In addition, this cartridge was used in the Thompson submachine gun. The table below indicates the Power of the cartridges relative to the super. I have loaded and successfully competed with this cartridge for many years and it is fun to shoot off a 1911 platform. Further, in a pinch you can use 9MM, which feeds and ejects just fine and is reasonably accurate.

9mm Luger 115 FMJ 1190 362 137 86.71%

38 Super+P 130 FMJ 1215 426 158 100.00%

357 Sig 125 JHP 1350 506 169 106.96%

40 S&W 180 FMJ 1000 400 180 113.92%

DVC

L-626

Stan Olsen

Base on the foot pound figures you provided, my math tells me that the 40 S&W has 93.9% of the power of the 38 Super. In fact, the 38 Super is commonly recognized as providing slightly more energy than either the 40 S&W or the 45 ACP!

Rob: Stanton’s numbers are correct. He is comparing typical factory-loaded “Power Factor” figures of the four cartridges. IPSC should have come up with a term other than “Power Factor” like “Recoil Factor” or “Impulse Rating,” although IPSC was correct in using a measure of a load’s Momentum rather than a load’s kinetic Energy, which is what you have done, to assess shooters’ abilities to realign their pistols at the target(s).

[“Power” is a poor word choice in this context because power is the rate energy is produced and/or expended; it says nothing about the relative values of the energy or time values. Let’s consider a 1.0 billion Watt laser, many of which exist, and it sounds like such a laser should blow whatever it hits to bits. Power is normally measured in Watts, where 1 Watt = 1 Joule per second. A Joule, J, is a little less than ¼ of a calorie, which is the amount of heat required to raise one cubic centimeter, cc, by one degree centigrade. To give you an idea of the sizes of a cc and a degree C, 12 fluid ounces is 355 mL = 355 cc, and one degree centigrade is pretty close to two degrees Fahrenheit. It’s actually 9/5. In other words, one Joule is a small amount of energy – a typical light bulb is converting 75 Joules of electricity into light and heat every second. Thus, if I programmed a laser to emit a pulse of light containing one Joule of energy for just one billionth of a second, the laser’s power output would be 1J/0.000000001 s = 1GW or one billion Watts, even though it would cause little or no damage to whatever it hit.]

Because momentum is always conserved, the magnitude of the momentum imparted on a firearm when it is fired is exactly equal to the magnitude of the bullet’s momentum the instant it leaves the firearm’s barrel. Any recoil experienced by a shooter for a given firearm is very much more dependent and proportional to a bullet’s momentum when fired from that particular firearm compared to the bullet’s kinetic energy fired from the same firearm. There are several reasons for this, however; with respect to firearms, the primary and overwhelming reason is that the momentum’s magnitude =̃ m•v, where m and v are the respective mass and muzzle velocity of the fired bullet, while the bullet’s energy (just as it leaves the muzzle) = ½•m•v^2 (The “v^2” term is the bullet velocity squared. At least with my internet browser, there is no way to form a superscript.) The principal significance between momentum and energy in this case is very clear – the bullet’s velocity is squared when calculating its energy. (Rob, I’m certain that you know that E=½•m•v^2.)

I see what you did Rob, and your calculations are also correct. We don’t need to worry about units because they cancel out. The energy of Stanton’s 38 Super bullet is ½•130•(1215^2) = 95.95 million, and the energy of the 40 S&W bullet = 90.00 million. The ratio of the energies, times 100 to make it percent, is 90.00/95.95 x 100 = 93.8%.

The 38 special is more powerful.

38 Special +p 125 JHP Silver Tip V=945fps E=247 Ft Lbs, (4" Vent Bl) < 38 Super +P 125 JHP Silver Tip V=1240fps E=427 Ft-Lbs (5"Bl)

Got a Lwt TALO Colt Commander and would like a Guardian in 38 SUPER.

Karl Kluge – As long as we're comparing the cartridges and not the guns the 38 super doesn't have anything on the 38 special. Elmer Keith was loading his 173 grain swc's over 13 grains of h2400 and getting 1200 fps+ from a 4" barreled 44/38. He went as high as 13.5 grains for close to 1300 fps and you can still do that today with a strong revolver because the 38 special case is bigger than the super case. There's no replacement for displacement.

Looks like you are comparing guns, 44/38. I still stand by my above numbers. He is overloading the cartridge and this is not a normal 38 Spl load. A 357 Mag with a 170 SWC (#358429) 13.5 gr 2400, V=1242fps, Pres=41,100cup. I believe the load noted would not be fun in a S&W Mod 60,357 let alone a Colt Detective Special or a S&W J frame. I like my Ruger SP101 3" 357 Mag, but not with the load noted. Over and out.

Well written. My girlfriend was given one by her dad. We took it to the indoor range and found some +P marked ammo there. I didn't know they were all marked+P. I did want to let you know I bought some Fiochi that is not marked +P last week at the gun show.

Well written. My girlfriend was given one by her dad. We took it to the indoor range and found some +P marked ammo there. I didn’t know they were all marked+P. I did want to let you know I bought some Fiochi that is not marked +P last week at the gun show.

Interesting caliber.

Interesting caliber.

I have a Kimber in .38 Super. Love the gun. Plan to keep it, and stay well stocked with ammo.

I shoot a Colt .38 Super Automatic – an ORIGINAL…I have owned it for 35+ years and it provides great pleasure and lotsa fun at the range. All I have to do is keep in mind two things about ammo – 1…not to use +P (per Colt’s Cust. Svc. Rep.) and 2…no hollow points. Ball ammo only. The feed ramp is antique and JHPs will jam all day long!

Accurate and a real conversation piece. Every time I go to a new range, I get one or two folks that want to purchase it…or I should say “steal” it for a small price! When I let them know that I know its true worth, they skulk off.

I shoot an EAA Witness chambered in .38 Super, though I usually use 9×23 Winchester ammo in it. Yes, it does fit and work. The .38 Super cartridge got a bad rap for inaccuracy way back in the 1930s when Colt headspaced their .38 Super 1911s on the semi-rim. That didn’t work well at all for accuracy. Also there was a bad fit between barrel and bullet diameters at that time… .355″ bullets in a .357″ bore don’t work well.

I launch 125 gr. JHP bullets at 1600 fps out of the 4.5″ barrel of my Witness and at 1450 fps out of a 3.6″ barrel on the same frame. With a 17+1 magazine capacity and the same ballistics as a .357 Magnum revolver I feel this is a great self-defense choice. Even with standard .38 Super +P loads it is pretty effective.

I got my introduction to the .38 Super back about the time that the IPSC boys were discovering it. I found an Astra A-80 pistol that I wanted at a gun show. I was looking for the .45 acp version, but the seller only had the .38 Super model. I bought it and never regretted the decision.

EastTN

I recently did a 22 TCM double mag conversion to 38 super and really like it. The 38 super is more pricey than 9mm, but a lot different and really fun to shoot. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of options for ammo. For a reloader this would be a great round.

I was fortunate enough to come across a moderately-used 1951 Super .38 Commander a few years ago.

Unlike the legend, the gun is quite accurate- my missus put the first six shots she fired out of it into a single hole at ten yards, even with the crunchy 6lb trigger and teeny original sights.

It’s never stopped or jammed, will run anything I put in it. It goes out the door filled with 11 CorBon DPX 125s, which clock 1260fps out of this old barrel. I use McCormick magazines.

My normal gun is a .45 Commander, but I can hit faster with the .38 and it holds two more. Both are perfectly reliable.

It’s a caliber war in my holster every morning.

I have a .38 super Colt pre war/ post war sold in 1946 but made in about 1942. It shoots great and has plenty of power. Most of all it is just a blast to shoot. I have about 20 pistols that I shoot, but it is more fun than any other. If a bad guy broke in my house it would be my go to gun over the .38 .357 .40 .45 or 9mm because it doesn’t kick and shoots as hard as my .357.