Exactly 53 years ago today, four California Highway Patrolmen died in a landmark gunfight now known as “The Newhall Incident.” Today, we’re focusing on one aspect of the Newhall Shooting: the officer who was slain as he reflexively stuffed empty brass casings into his pocket while reloading his revolver. It’s an often-repeated cautionary tale about the dangers of unrealistic training. And it’s 100% false.

Details are in the video below, or keep scrolling to read the full transcript.

EDIT: Some of our viewers have brought to our attention a story from Bill Jordan that was likely conflated and combined with the Newhall Incident to become the myth we know today. Details below after the transcript.

The Brass Myth

Have you ever heard the story about the cop who was killed in a shootout because he stopped to pocket the empty brass from his revolver while he was reloading? Well, it turns out that probably never happened.

Hey everybody, I am Chris Baker from LuckyGunner.com. Today we’re going to talk about this myth – where it came from, what really happened, and how it still impacts defensive firearms training today.

The story is most often told to illustrate the danger of so-called “training scars.” That’s the theory that certain habits we unintentionally develop during training might turn out to be counterproductive when we have to actually perform under real pressure.

In this scenario, the policy of the police shooting range had supposedly conditioned this officer to immediately pocket his empty brass casings every time reloaded his revolver. When he got into a real gunfight, he reverted back to that behavior. His assailant caught him off guard either while he was collecting these cases or pocketing them. His body was found with an unloaded gun and empty cases in his pocket.

So the moral of the story is to “train how you fight.” Make your training as realistic as possible… or you might die. It’s not a bad lesson, but unfortunately, the story itself is probably fictional.

I say “probably,” because it’s possible something like this might have happened to some officer somewhere. We can’t know for sure. But it’s usually associated with the infamous 1970 Newhall shooting, and it’s almost certain it did not happen there.

The 1970 Newhall Shooting

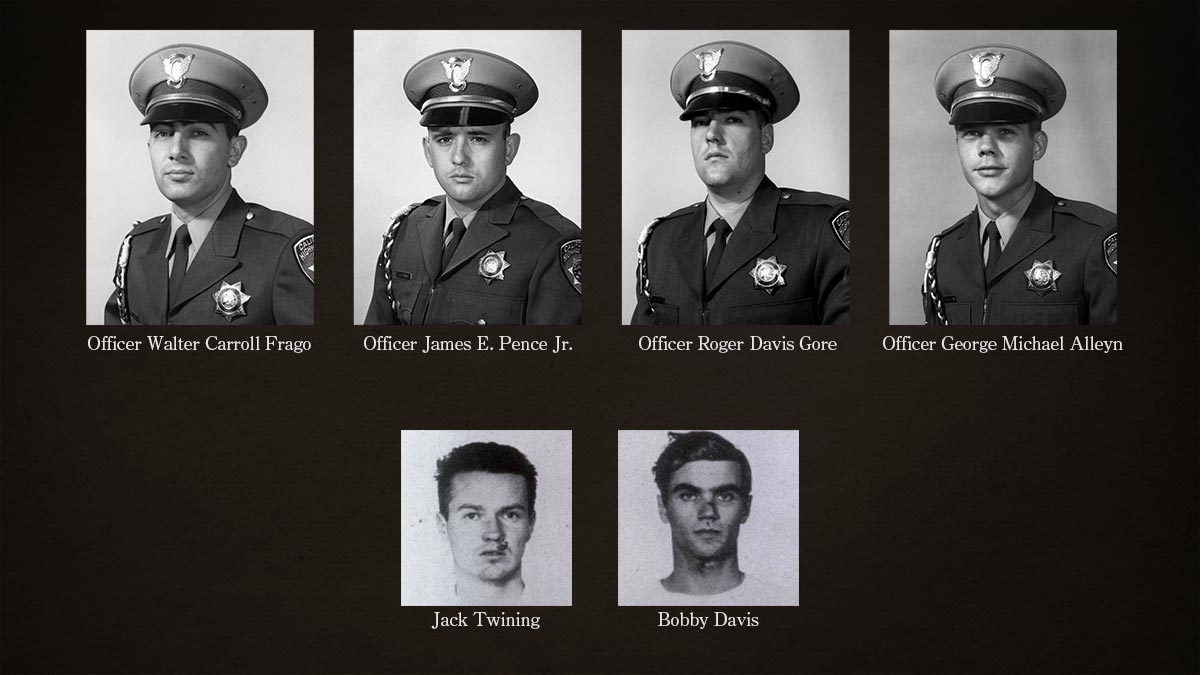

The Newhall Incident – sometimes called the Newhall Massacre – is one of a handful of events in the 20th century that drove major changes in law enforcement training nationwide. Four California Highway Patrolmen were killed by two suspects during a traffic stop. Newhall has been covered in great detail in numerous articles, videos, and books. If you really want to get into it, I recommend the book Newhall Shooting: A Tactical Analysis by Mike Wood. Mike also happens to be the senior editor of the excellent Revolver Guy blog.

What Happened in Newhall

The basic gist of the story is that two California Highway Patrolmen pulled over a suspicious vehicle late at night. The two occupants pretended to comply at first, but then shot and killed both officers. Before the suspects could escape, another pair of officers arrived in a second patrol car. They exchanged gunfire for a while, and eventually those officers were killed as well. More officers arrived as the suspects escaped on foot. One of them surrendered a few hours later, and the other committed suicide after a brief hostage standoff.

The California Highway Patrol made several changes to their policies and training program in the aftermath. For example, at the range, they required officers to eject their empty brass onto the ground to clean up later. Previously, they would eject empties into their hand or a bucket. The “pocket full of brass” rumor most likely started when someone heard about the policy change and assumed it was a direct result of a specific mistake made by an officer at Newhall. The rumor made its way into law enforcement publications and gun magazines. Numerous variations of the story still remain a part of gun culture and cop lore more than 50 years later.

There was an attempted reload during the Newhall Incident, but it failed for different reasons than the myth. The true version of the story comes with its own set of cautionary lessons that have also become part of common firearms training doctrine.

Pence’s Reload Attempt

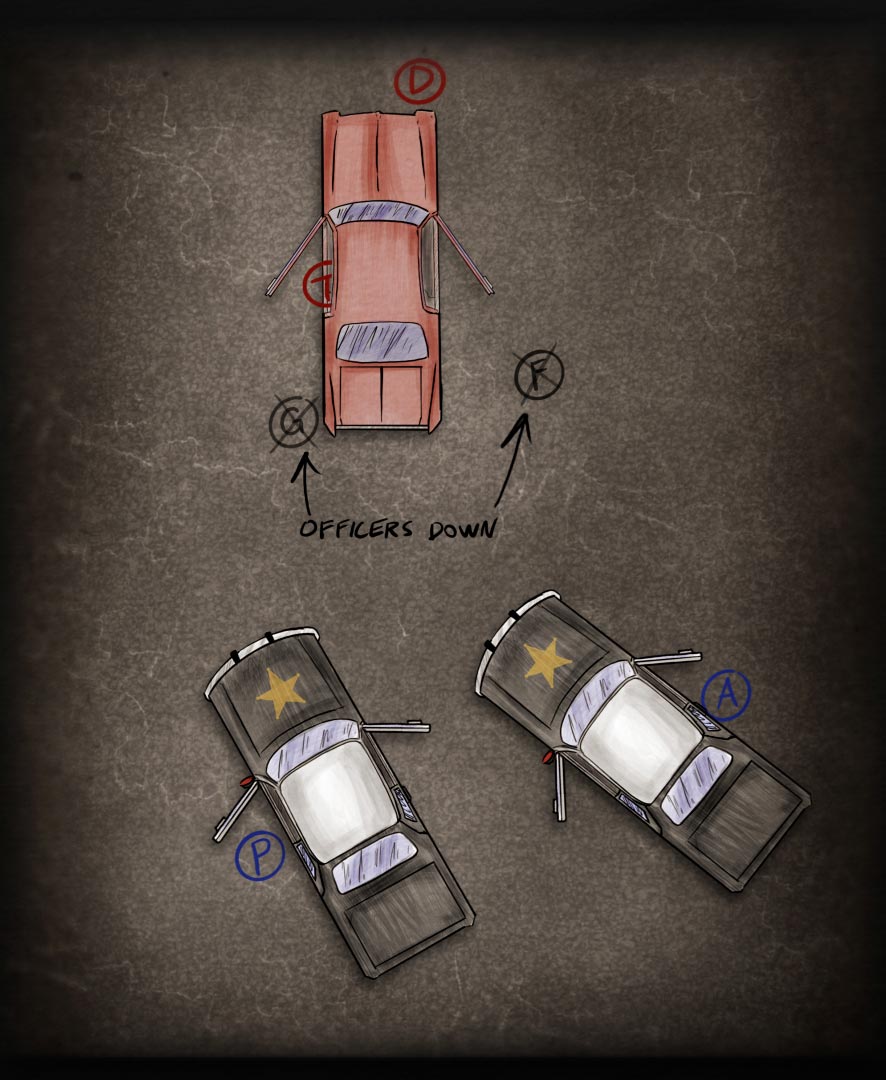

The reload was attempted by Officer James Pence with his six-inch .357 Magnum Colt Python. Pence and Officer George Alleyn were in the second patrol car that arrived on the scene. At that point, the suspects Jack Twining and Bobby Davis had just killed the first two responding officers and were already shooting at the second car as it pulled up.

While Pence radioed for backup, the suspects both entered the passenger side of their vehicle to retrieve more firearms. Pence exited the driver’s side of his patrol car and returned fire, but missed with all six rounds.

He then retreated to the rear of the car and took cover in a kneeling position to reload. During that movement, he ejected his empty shell casings which investigators later found on the ground.

Pence had his spare ammo in a dump pouch on his right side. Departments didn’t issue speed loaders at that time. With a dump pouch, you would unsnap the flap and the rounds would fall into your hand. So he was reloading his revolver one round at a time. In the meantime, Twining advanced over to Pence’s left side. With a Colt 1911, he shot Pence four times: twice in the lower torso and once in each leg.

Pence continued loading his revolver. He got the sixth round in the chamber and was just about to close the cylinder. But by then, Twining had advanced to within just a few feet. He fired one final shot that struck Pence in the back of the head, killing him instantly.

This version of the events is supported by eyewitness reports and the physical evidence investigators collected at the scene. They didn’t find any brass in Pence’s pocket. Crime scene photos show all six shells on the ground next to the rear driver’s side door of Pence’s patrol car.

Realism in Training

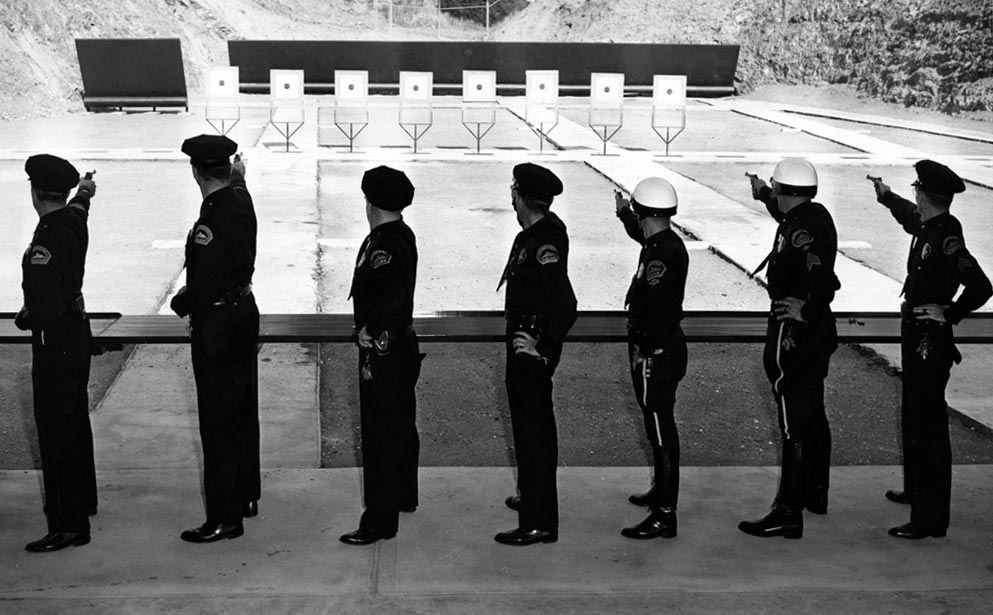

So the “pocket full of brass” training scar story is undoubtedly false. But there was a very real problem with a lack of realism in police firearms training at the time and that was one of many contributing factors to the Newhall tragedy. The California Highway Patrol had a somewhat progressive training program relative to other agencies, but they still did very little to prepare officers for real-world violence.

The majority of their shooting on the range was done using a one-handed grip with the support hand on the hip in a bladed competition-style stance. Department firearms instructors considered all four of the slain officers to be outstanding marksmen. Yet none of them managed a direct hit on either of the suspects during the gunfight.

Emergency reloading was not a skill academies taught or practiced. Shooters would load their guns from boxes or trays on a table at the firing line. It’s very possible Pence never attempted to use his dump pouch until the night he was killed.

I wanted to get an idea of how fast this kind of reload technique would be, so I tried it out at the range. We don’t have an old fashioned dump pouch or a six inch Python, so I used a Smith & Wesson Model 64 and just pulled the loose rounds from my pants pocket. It’s not quite the same, but either way, you’re loading six rounds with a handful of cartridges that are in no specific orientation.

My first attempt was 17 seconds. After several more tries, I had one that felt like it went pretty smoothly and that was 13 seconds. Even if Pence somehow managed to reload his Python in only 10 seconds, that would have still given Twining plenty of time to flank him.

Task Fixation

And that brings us to another commonly taught training point that likely originated with Newhall — the idea of task fixation. Pence seemed to be completely focused on loading his gun. He knew his life depended on completing that task. There was no room in his brain for attempting to keep up with his attacker’s position.

Some firearms instructors are emphatic about avoiding this, and they’ll even use Pence as an example. You might hear phrases like “keep your head up” or “keep your eyes on the threat.” Again, that’s probably good advice, in principle. You don’t want to get preoccupied with your equipment and lose track of what’s going on around you. But it’s often taken to extremes, like the modern “no-look reload” – the idea that if you even glance at your semi-automatic pistol while you’re reloading, the bad guy is going to take advantage of that and catch you off guard.

I don’t know if that’s what we should be taking away from the Newhall incident. I think a more relevant lesson is the importance of unconscious competence. Operating the gun should not require any conscious mental effort. You don’t usually have to be the quickest or the most accurate as long as your gun handling skills are on auto-pilot. That frees up mental resources for other important things like who needs to be shot and who doesn’t. Or you might be able to maintain the presence of mind to look up every once in a while during your 15 second revolver reload.

Adopting the Speed Loader

On top of the training issue, events like Newhall always bring up questions about equipment. In hindsight, we could make the argument that the officers would have been better off with higher capacity semi-autos. That was such a foreign concept in police culture at the time that I don’t know if CHP seriously considered it in the immediate aftermath of Newhall. But they did begin to issue speed loaders instead of the dump pouches.

After a little practice, most shooters can learn to reload in about five or six seconds with a speed loader. With a duty-style speed loader pouch, I can pretty consistently pull it off in a little less than five seconds under ideal range conditions. Sometimes under four seconds if I get lucky. That’s with a Safariland Comp II speed loader, which didn’t come around until the 80s. But some of the 70s-era speed loaders were just as fast. A speed loader would have been a massive advantage for Officer Pence, even if he had not spent the time to become super fast with it. It’s not just faster than a dump pouch, it’s a much more reliable and stress-resistant way to reload a revolver.

Partial Revolver Reload

Pence could’ve opted for a partial reload. Tragically, something instructors probably never taught him. There was no reason Pence had to load all six rounds before returning fire. That’s part of the problem with the task fixation in his particular case. If he had seen Twining coming up on his left, he could have just closed the cylinder right then with however many rounds he had loaded up to that point.

I attempted the same single-round loading procedure as before, but I stopped after getting three rounds in the cylinder. I didn’t even attempt to line up the loaded chambers with the barrel, I just closed the cylinder and started on the trigger. That cut my reload time down to eight seconds. That’s still basically an eternity in a gunfight. But a partial reload would have gotten Pence back in the fight a few seconds earlier.

The Bigger Picture

We’ve just been looking at a very narrow slice of the Newhall Incident today. I don’t want to give the impression that the whole event hinged on a revolver reload. By the time Pence held an empty gun, they’d already made a number of mistakes. I focused on the reload because I want to help set the record straight on the pocket full of brass myth.

We all want to learn from tragedies like Newhall so innocent people don’t die in vain. To do that, we really need to start by making sure we have our facts straight. And we also have to apply some wisdom and care when we analyze these unique outlier incidents. They’re almost always the result of multiple layers of failure. We can’t do justice to the lessons learned by just repeating vague platitudes like “train how you fight.”

Special thanks to Jay Grazio for the video clip of the dump pouch. I hope you guys found this interesting. If so, do me a favor and subscribe to our channel and the next time you need ammo, get it from us with lightning fast shipping at LuckyGunner.com

Addendum

After posting this video on YouTube, we heard from multiple viewers who suggested another possible origin for the brass myth. In the book No Second Place Winner (first published five years before Newhall), Bill Jordan relates a story about an officer who found brass in his pocket after a gunfight. The full text is available for free from the Internet Archive (PDF). The relevant story appears on page 106.

“Well, after the fight someone noted that McKone’s pocket was bulging and politely inquired as to what might be spoiling the drape of his trousers. Puzzled, Sam thrust in an exploring hand. The pocket was full of fired cases. During the fight, without realizing he was doing so, McKone, an old reloader, had saved every empty!”

As I mentioned above, there are many versions of the brass myth, but they almost all involve the officer reflexively gathering or pocketing brass because of his training and dying in the end. While the officer in Jordan’s story lives and collects brass for a different reason, it’s an obvious starting point for the later distortions.

It’s also worth noting that the officer in Jordan’s story engaged with a rifle-wielding suspect positioned 200 yards away. Pocketing his brass was not the fatal error it would have been in a close-range encounter. Though the story is offered as a lighthearted example rather than a tragic one, Jordan uses it to illustrate a lesson similar to those drawn from Newhall (both the real and fictional versions): that people will “automatically do what they have been trained to do, provided that training has been thorough and intensive.”