It’s time for part two of our Lever Action Rifle Series! Today, we’re looking at .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum when fired from lever action rifles (in this case, two identical rifles — a pair of Henry X Models). What’s the useful range of these cartridges with rifle length barrels? We tested that. What kind of performance benefit do they offer versus handguns chambered for the same calibers? We tested that, too. And some ballistic gel testing, hard barrier penetration testing, and a whole bunch of pretty charts, numbers, and spreadsheets… if you’re into that kind of thing.

Details are in the video below, or scroll on down to read the full transcript.

Hey everybody, Chris Baker here from LuckyGunner.com. It’s time to continue our series on lever action rifles. In our intro to this series, I asked you guys what kind of lever action topics you wanted me to cover. You responded with an enormous variety of requests. Some of that stuff I’ve already planned to cover and some of it I never would have thought of on my own. So thanks for sending me some great ideas.

Among the most common requests were topics relating to .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum. Some of you asked which is the better cartridge for lever actions. Which one is more useful? How do the ballistics compare? And how do lever action ballistics for these calibers compare to the same loads fired from a revolver? I am going to cover all of that and more today in the second installment of our lever action series.

The Test Guns and Ammo

Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve shot several tests and taken a bunch of measurements with these two cartridges. For my test rifles, I’ve been using a pair of Henry X Models. These rifles are pretty much identical except one is chambered for .357 Magnum and the other for .44 Magnum. Both have 17.4-inch barrels. They have the same sights, same trigger. That gives us an even playing field for our ammo testing.

I picked five different loads for each cartridge for these tests — ten loads total. Of course, ammo availability is extremely limited right now. That’s as true for me as anyone else. This is all ammo I put aside several months ago when I first started planning this series. Both of these cartridges have a huge variety of loads available. Obviously, I couldn’t cover them all, but I tried to gather a broad spectrum of bullet weights and bullet types from the major manufacturers.

I also, for the most part, avoided ammo that is specifically marketed for self-defense because those loads are usually optimized for handgun-length barrels. When you push those bullets too fast, they often over expand and under-penetrate. I wanted to use loads that might have a better chance of letting these cartridges show off their true potential with a rifle.

That extra velocity can improve the range and effectiveness of these bullets, but only to a point. .357 and .44 Magnum are still handgun cartridges. They’re not going to give us the performance of a true rifle cartridge. That fact quickly becomes evident when you look at the bullet trajectory for these rounds.

.357 Magnum vs .44 Magnum Bullet Trajectory

That’s the first test I performed. For each of the 10 loads, I fired groups from the bench at 50, 100, 150, and 200 yards. Then I measured the distance from the bullseye to the center of the group to get a general idea of how far the bullets drop at that distance. To make it easier to compare the results, before I shot the groups with each load, I re-zeroed the rifle at 100 yards for that load.

The Henry X Models come with fiber optic open sights. These are pistol-style sights that are great for snap shooting at close range. They’re not so great for shooting groups or making fine adjustments to the zero. Normally, I would not suggest mounting a magnified optic on a pistol caliber lever action. It kind of takes all the fun out of them. But I did in this case, just for the purpose of shooting some groups.

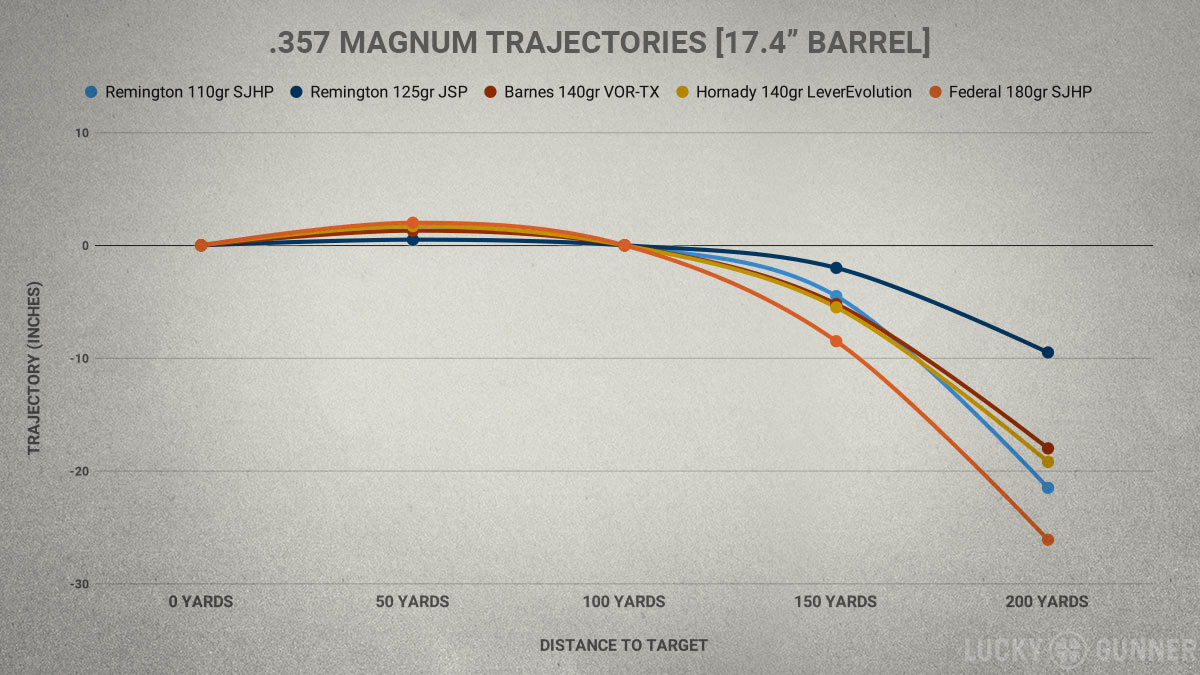

So let’s take a look at the results. Here’s a chart showing all of the .357 Magnum loads.

At 50 yards, all five loads were hitting between .5 inches and 2 inches high. That’s more or less what you expect with any rifle with a 100 yard zero. So at 100 yards, of course, they’re all hitting right at the bullseye.

Things get more interesting at 150 yards. The 125-grain Remington JSP only dropped 2 inches at that range. Three of the five loads dropped around 5 inches. And then our heaviest load — the Federal 180-grain — dropped the most at 8.5 inches. The wheels really start to fall off at 200 yards. The 125-grain Remington was almost 10 inches low. All the others were between 18 and 26 inches low.

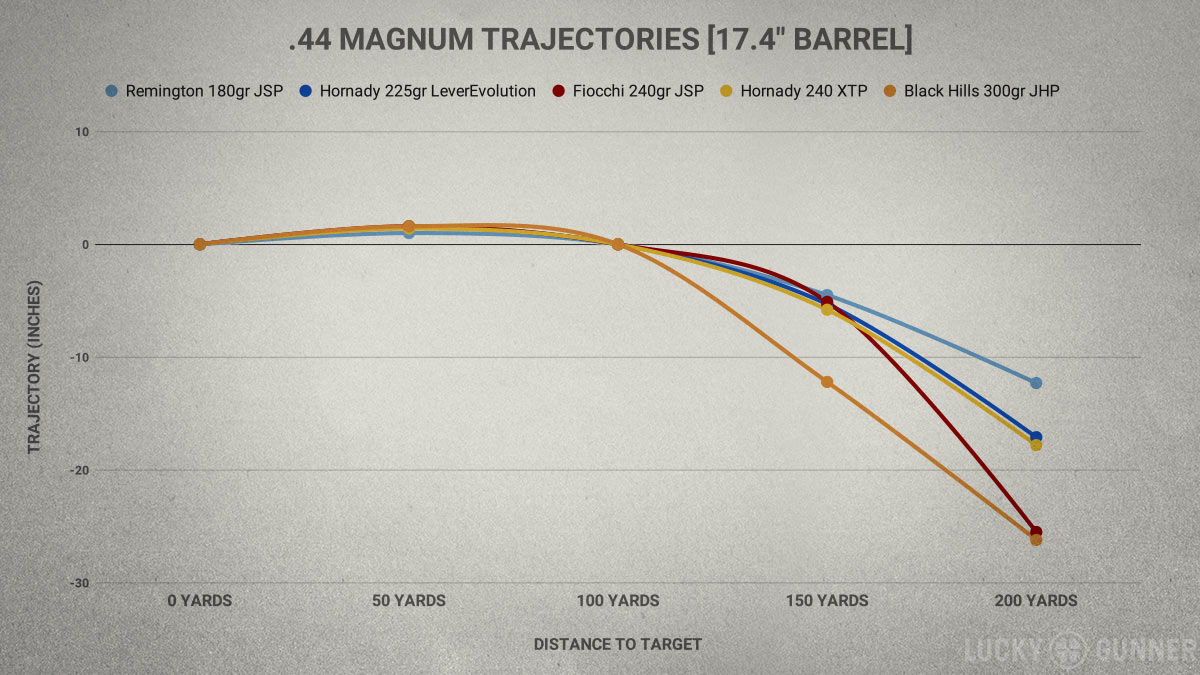

I got similar results with the .44 Magnum loads

Again, we’re an inch or two high at 50 yards. On the bull at 100. At 150, four of the five loads were in the -4 to -6 inch range. The heaviest .44, which was a 300-grain Black Hills, dropped like a rock at -12 inches. At 200 yards, the Fiocchi 240-grain joined the Black Hills load at -26 inches. The two Hornady loads were around 17 inches low and the lightest of the 44s — a Remington 180-grain — dropped 12 inches.

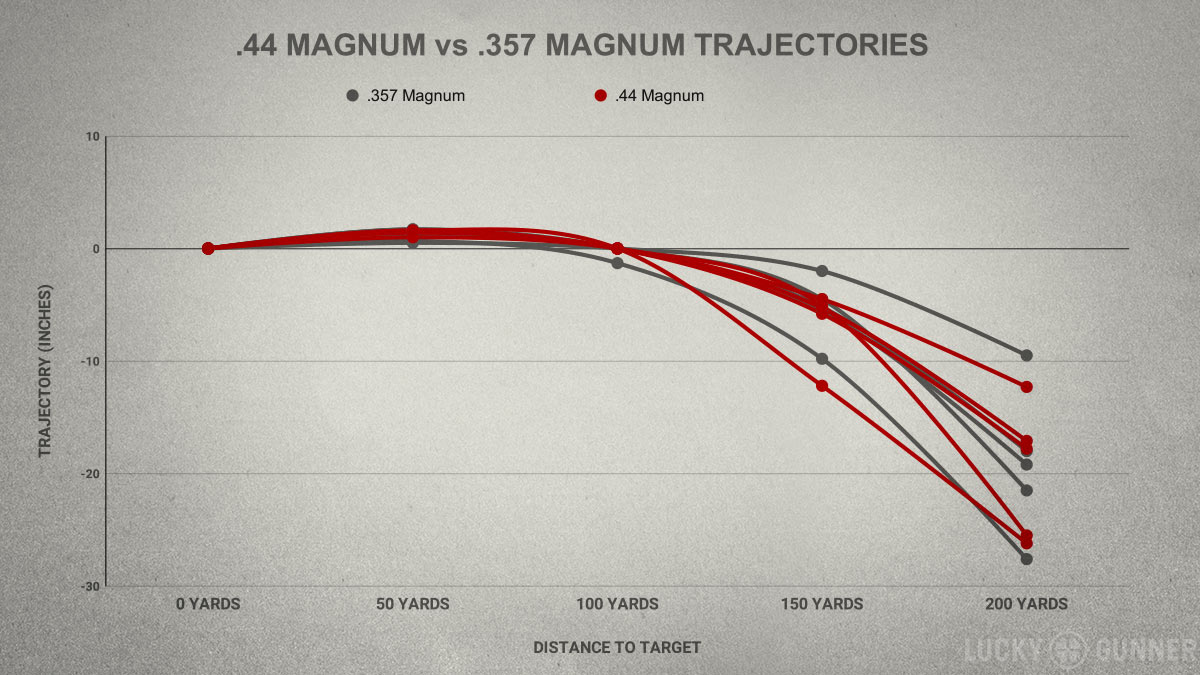

Here are all the results for both cartridges together.

The .357s are in grey and the .44s are in red. Overall, they’re pretty comparable. If you had to pick which cartridge was flatter shooting, you’d need a lot more data from a lot more loads, and I think it would still be pretty close.

So, best case scenario, a .357 or .44 Mag lever action is probably a 150-yard gun unless you’re just really a superstar at range estimation. Realistically, for most of us for any practical purpose, it’s more like a 100 to 125 yard gun with some wiggle room. If you used a flatter shooting load and played around with your zero, you could maybe stretch it out past 150 in a pinch. Personally, if I thought there was a decent chance I might need to shoot something that far, I’d go with a rifle caliber.

.357 Magnum vs .44 Magnum Velocity and Energy

When I shot these groups, I also took velocity readings with our LabRadar. This device measures the muzzle velocity just like a chronograph does, but it also can also tell us the velocity at various increments as the bullet moves down range. I had it set to give readings at 50, 100, and 150 yards. I also tried 200, but it had trouble picking up the bullets that far away.

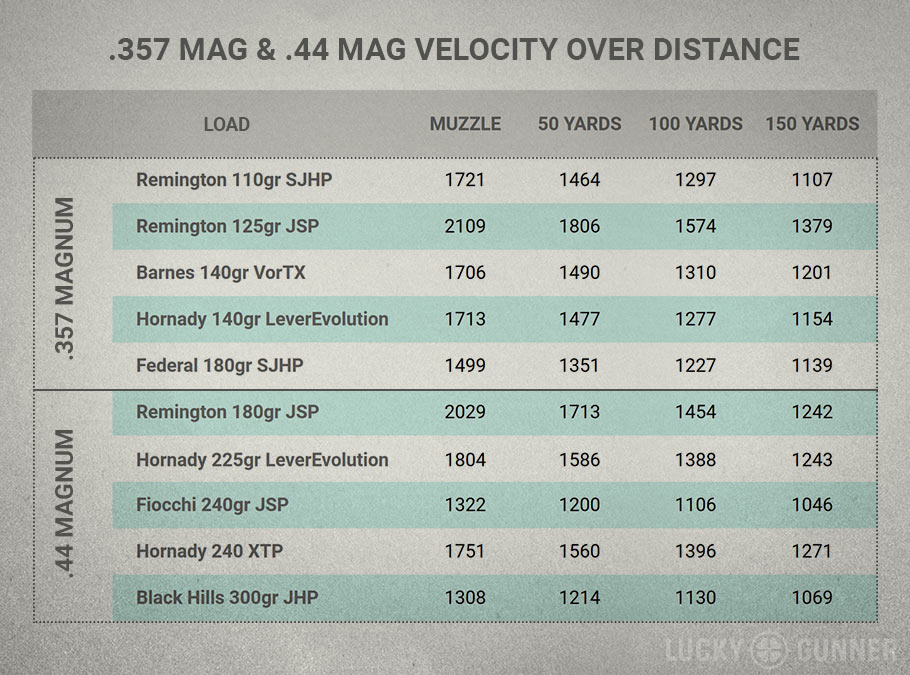

There’s a lot of cool stuff we can do with these measurements. First, I’ll just show you the raw data in case you spreadsheet enthusiasts want to pause the video and copy that down.

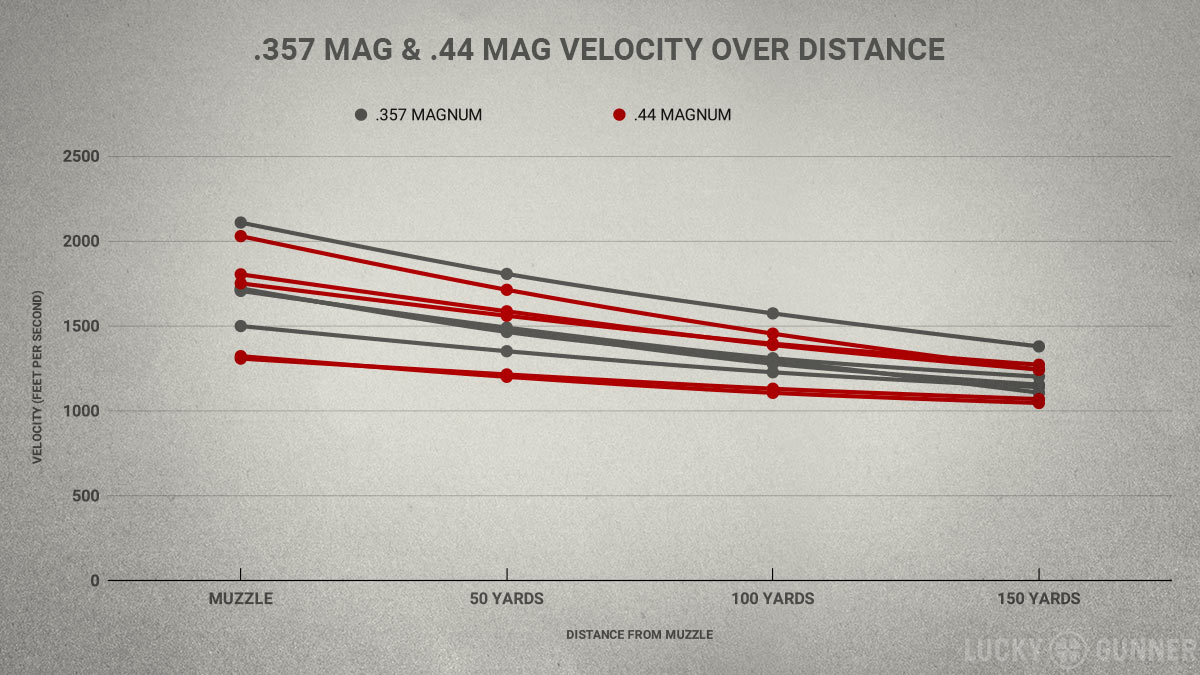

If we put that on a chart, we can get an idea of how much velocity these bullets are losing over distance.

We can also see that even though the .357s might average out to be a little faster, there is a lot of overlap. Both cartridges have loads on the slow end and on the faster end of the spectrum.

In addition to the rifles, I also took velocity measurements with a couple of 4-inch revolvers. For .357 Magnum, I used a Ruger GP100. The .44 Magnum was a Smith & Wesson Model 629.

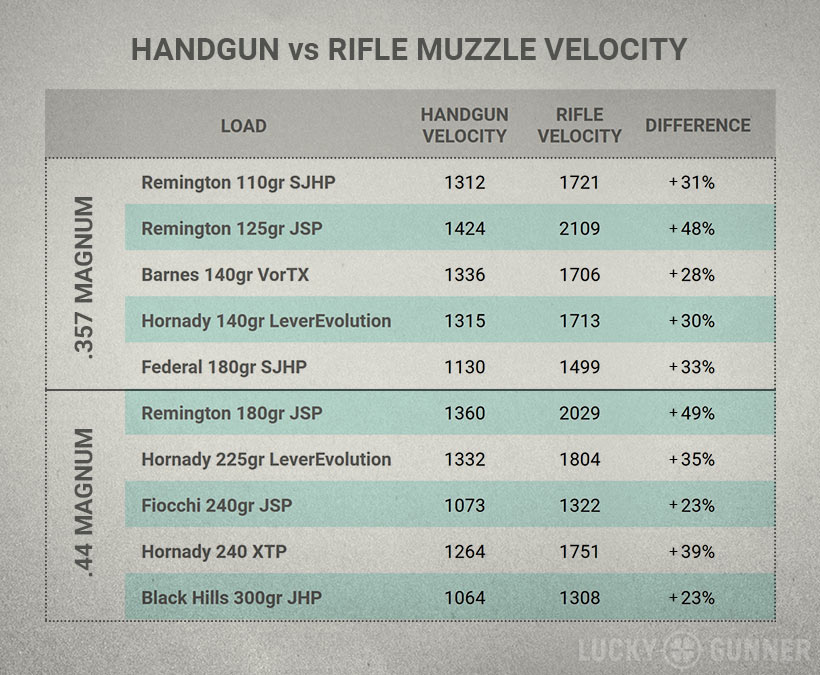

For the handguns, I only recorded the muzzle velocity. So here we’ve got the handgun muzzle velocities next to the rifle muzzle velocities and then the percent increase.

The smallest velocity increases were in the low 20s, which is still a major change. Half of the loads had an increase in the 30s and two of them were right there at almost 50 percent. In a minute, we will see what kind of impact that velocity increase had on the ballistic gel performance.

We’ve got the handgun muzzle velocities and we also know the rifle velocities at various increments. With that, we can make a reasonable estimate as to the distance where the rifle velocity is equal to the handgun’s at the muzzle.

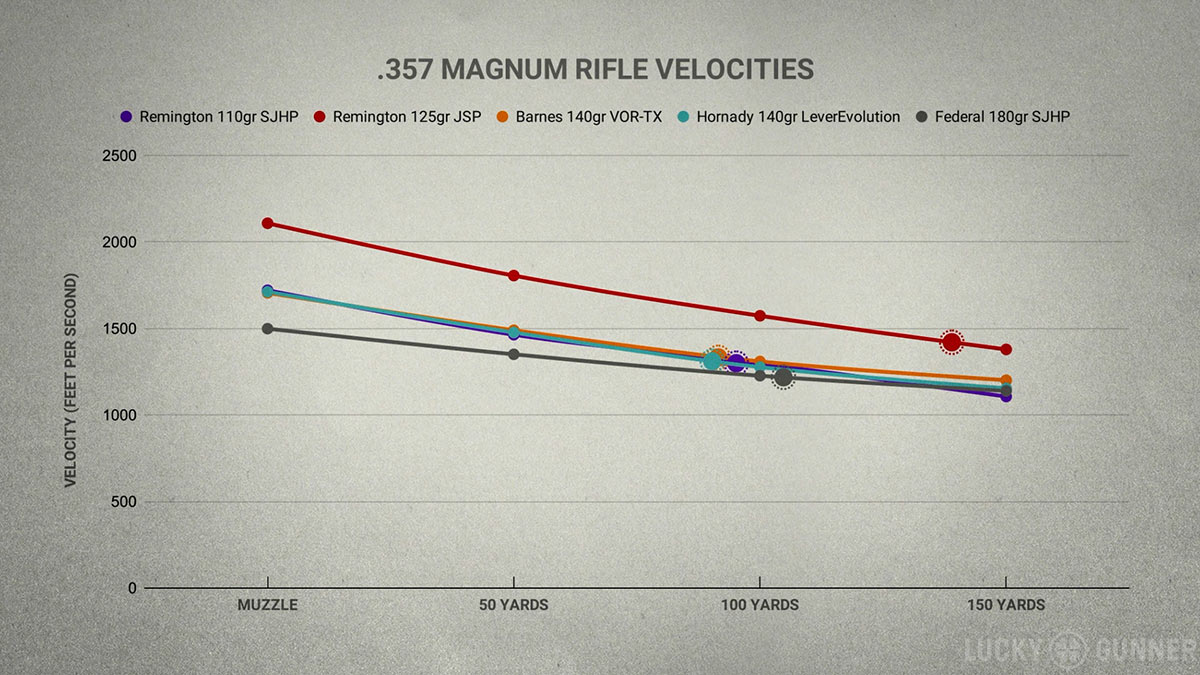

Here’s that chart again with the .357 Magnum velocities from the Henry lever action. [Handgun muzzle velocities appear as larger circles with a dotted outline.]

With the revolver, the 125-grain Remington had a muzzle velocity equal to the rifle’s at 138 yards. The other four loads all had handgun velocities that matched what the rifle was doing between 90 and 105 yards.

So if you shoot something with your .357 Henry that’s 100 yards away, it’s basically like shooting it point blank with a 4-inch revolver.

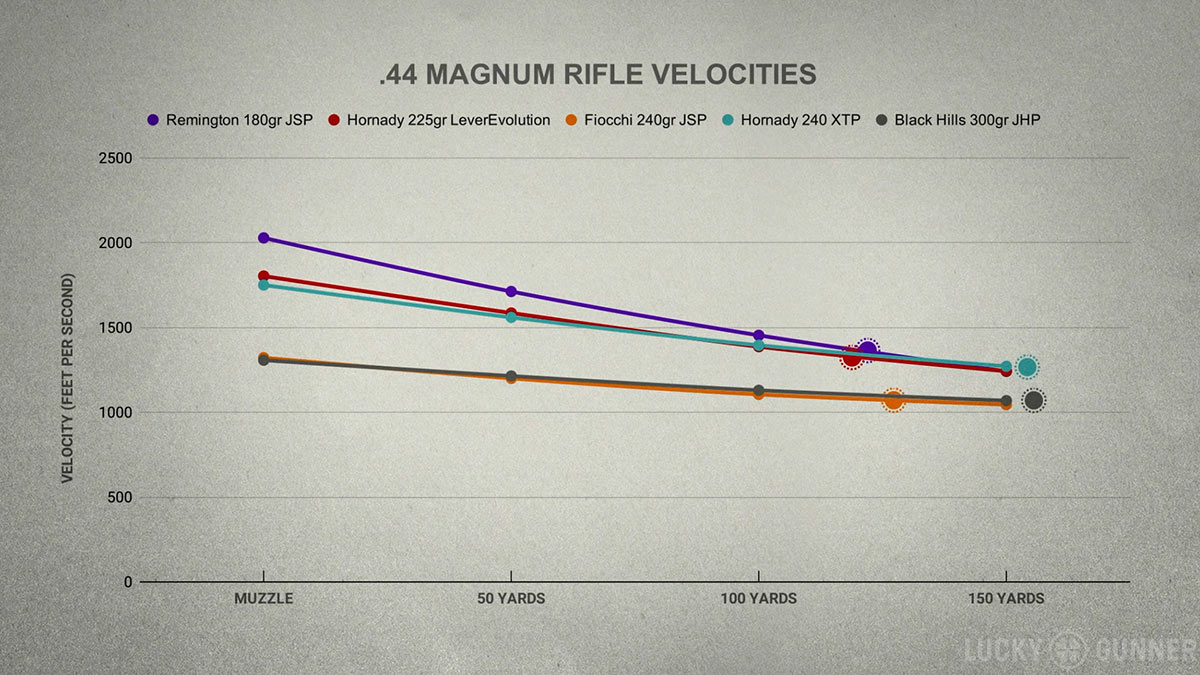

The disparity between rifle and handgun was even more dramatic with the .44 Magnums. The handgun velocity with the Hornady XTP and the Black Hills were both slightly less than the rifle velocity at 150 yards. For the other three, the converging point was in the 120 to 130-yard range.

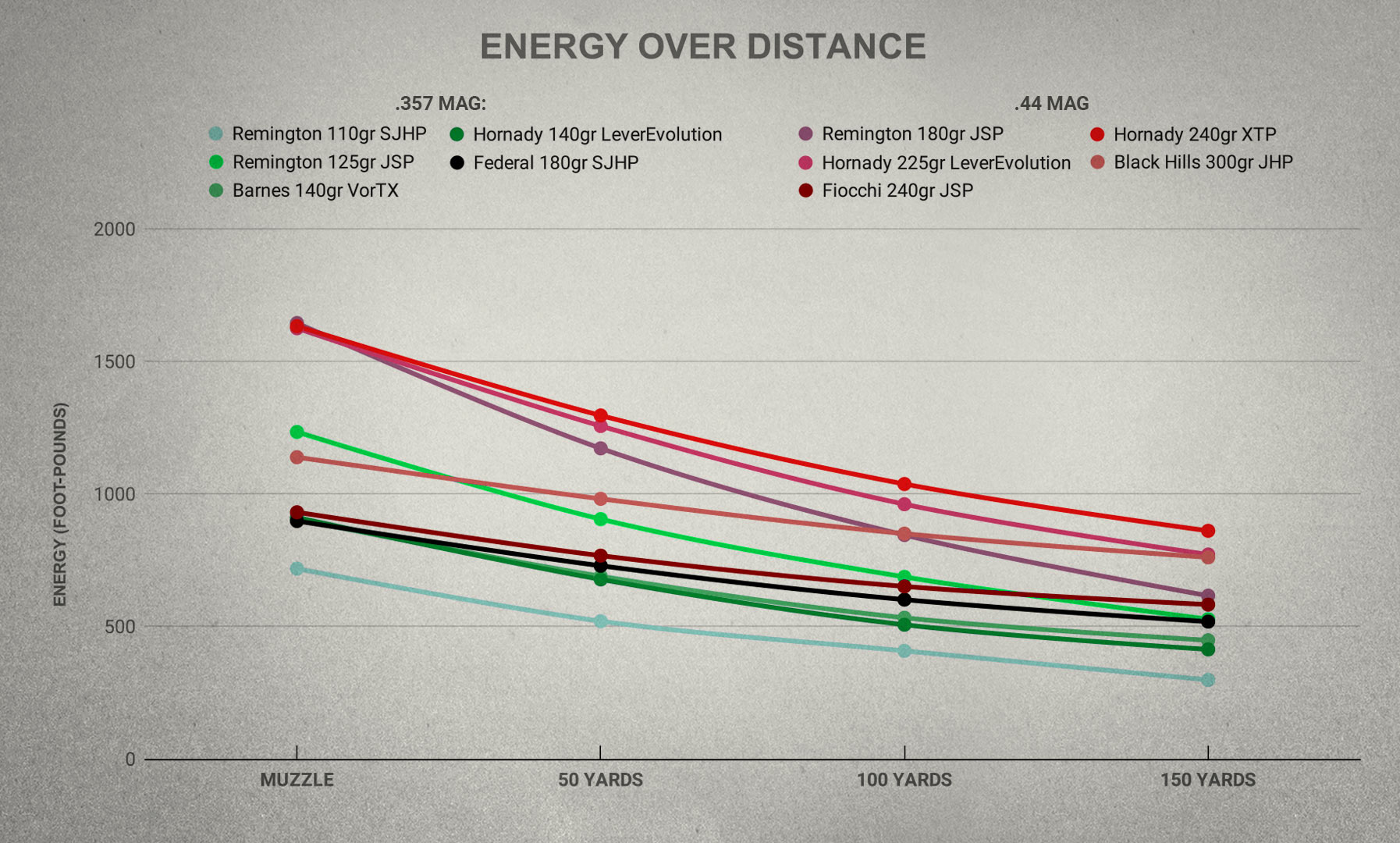

There’s one more thing we can do with these velocity numbers. If you know the velocity and you know the bullet weight, you can calculate the energy of the bullet. Here’s a chart showing the bullet energy in foot-pounds for all 10 loads when fired from the rifles.

Three of the .44s started out at around 1600 ft-lbs. That’s getting close to the energy of a light .30-30 Winchester load. The other two .44s were way behind. That 125-grain Remington .357, again, has proven to be an outlier. It’s starting out at bit over 1200 ft-lbs, which is roughly 300 foot pounds greater than the next .357. But it’s not some kind of special snowflake load. There are plenty of factory .357 loads that can put up these kinds of numbers. The Remington just happened to stand out in this batch of five.

As we’ll see in a minute, energy is not everything. I don’t want to over-emphasize it, but it’s easy to measure and it’s a way to compare apples to oranges when we’ve got bullets with different weights and velocities. In this case, I think these numbers demonstrate just how important load selection is and how much of a difference the longer barrel makes.

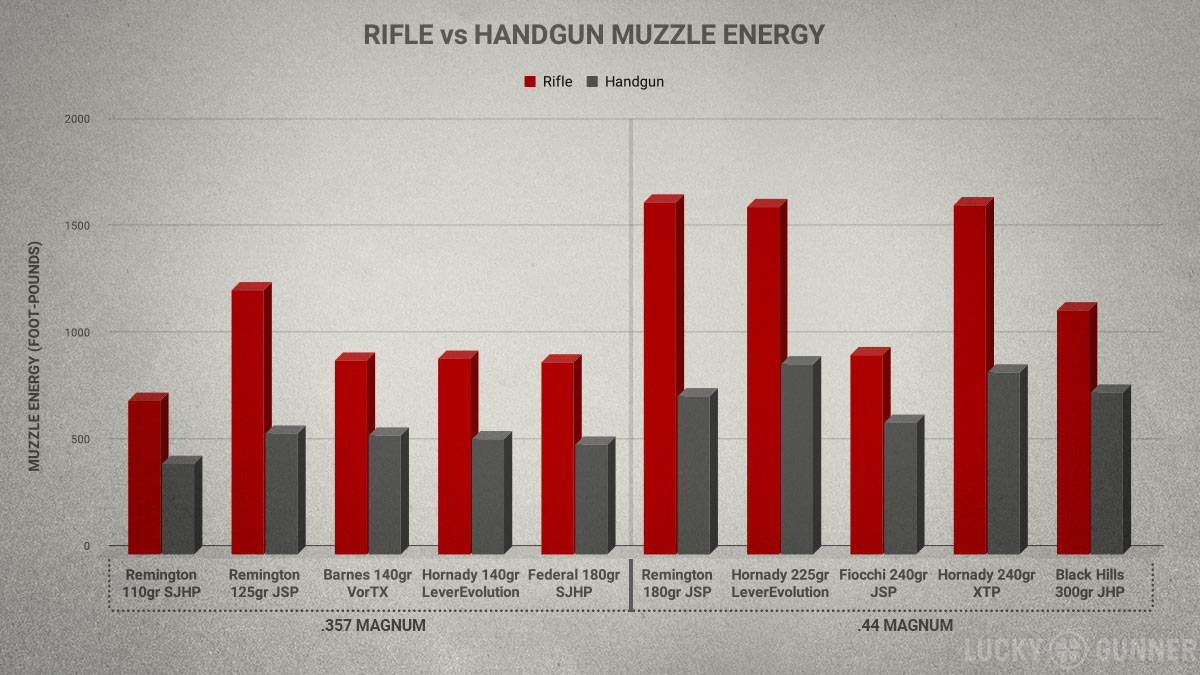

Here’s one more chart for you. This is showing the energy at the muzzle for each load. The reds represent the rifle muzzle energy and the greys are for the revolver.

Compare the red bars on the left to the grey bars on the right. Just by firing it out of a longer barrel, a .357 Magnum will meet or even well exceed the muzzle energy of a .44 Magnum from a handgun.

.357 Magnum vs .44 Magnum Ballistic Gel Tests

Okay, let’s move on to the terminal ballistics. For the ballistic gel testing, I used synthetic gel blocks from Clear Ballistics. Each block is 16 inches long and I lined up two of them longways. I fired one round of each load with the handgun and one round with the rifle. I would have preferred to fire at least two or three rounds of each load to make sure there was some consistency. But with a short ammo supply, I had to settle for one round per test.

Starting with the .357s, the Remington 110-grain hollow point was just moving too fast. This is one of those self-defense loads I was talking about earlier. It’s designed with handguns in mind. But in this test, with both guns, it expanded too much and too soon which led to severe under-penetration.

The Remington 125-grain jacketed soft point didn’t have enough velocity with the handgun to open up. It zipped right through both blocks. With the rifle, it expanded nicely with decent penetration.

The next three loads all performed more or less the same with the rifle as they did with the handgun. Not a major difference in either penetration or expansion with any of those. They all had solid solid numbers.

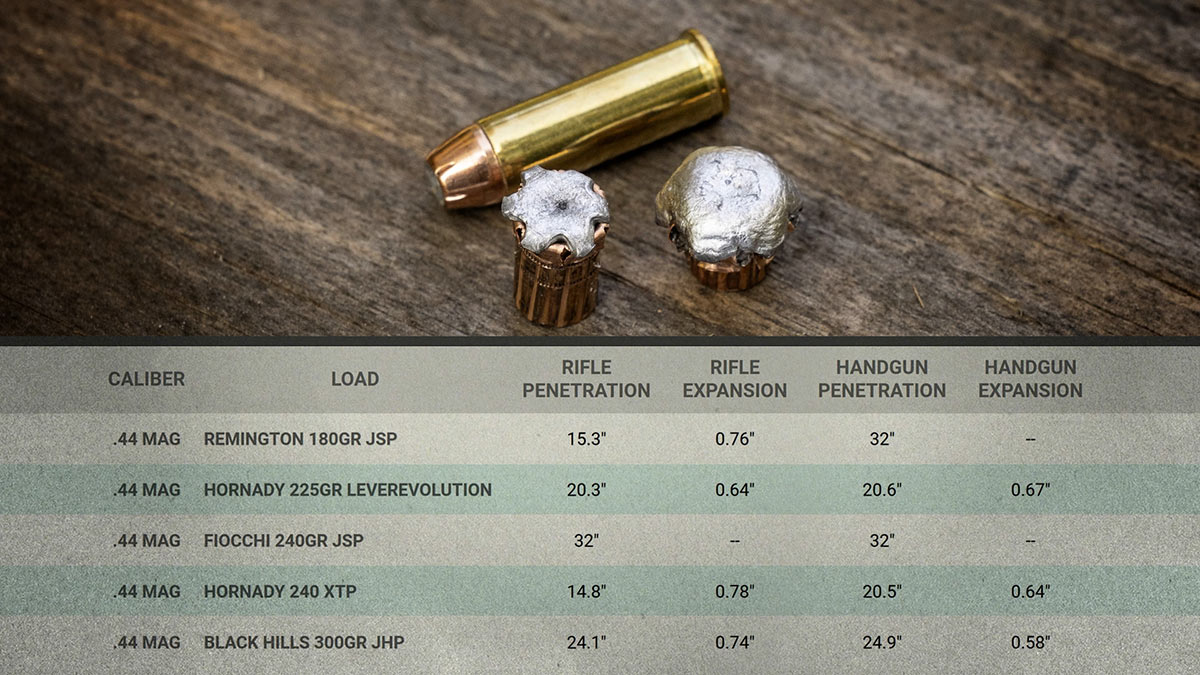

Moving on to the .44s, The Remington 180-grain soft point did the same kind of thing as the .357 soft point. No expansion with the handgun and lots of expansion out of the rifle with moderate penetration.

The Hornady LeverEvolution had nearly identical performance with both guns. The Fiocchi 240-grain, again turns out to be kind of a powder-puff load. The velocity was just too low to get any expansion out of either the handgun or the rifle.

The Hornady XTP showed us that classic inverse relationship between expansion and penetration. It did okay out of both guns, but we got more expansion with the rifle and more penetration with the handgun.

The Black Hills 300-grain JHP was kind of interesting. It had nearly equal penetration out of both guns, but with the rifle, there was almost 50% more expansion.

If we look at all the data together, it’s pretty clear that you can get decent performance with either cartridge. The .44s will obviously have a larger expanded diameter on average. But generally, the absolute diameter of the bullet doesn’t matter as much as simply whether the bullet reliably expands or not.

The shape of an expanded bullet crushes and tears tissue more effectively than the shape of an unexpanded bullet. Both of these cartridges have loads that will do that really well without sacrificing penetration.

.357 Magnum vs .44 Magnum Hard Barrier Penetration Test

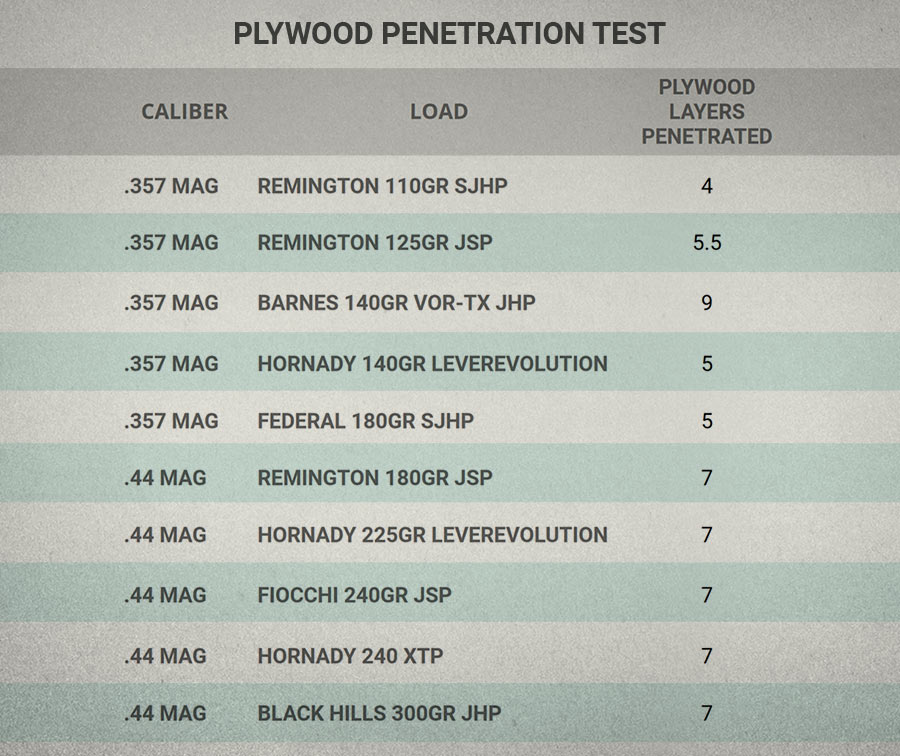

The final test I performed was the hard barrier penetration test. For this, I used pieces of ⅝-inch plywood. I lined up 18 sheets with a little gap in between each one. The idea was to just find out how many sheets of plywood the bullet could penetrate before it stopped. I only did this test with the rifles, not with the handguns. Again, it was an issue of ammo availability.

The wood I used was kind of old and dried out, so I wouldn’t compare these results to any other wood penetration tests. In general, wood is not a great medium for repeatable testing because it changes so much based on its environment. But this should at least show us how these .357 and .44 loads compare to each other.

The plywood is not meant to simulate bone or thick brush or the walls in your house or any other specific barrier. It just gives us a general idea of how these bullets might behave when they have to punch through hard things.

The 110-grain Remington was, again, the poorest performer of the lot. It only made it through four sheets of the plywood and left a big dent in the fifth. The 125-grain Remington went cleanly through five sheets of plywood and almost, but not quite through a sixth. I’m going to call that five and a half. Both of those bullets expanded and left big nasty exit holes in the wood they penetrated.

The Barnes VOR-TX all copper hollow point was actually the exception in that regard. It was the only load out of all ten that did not expand at all in the wood. But that, in turn, led to much better penetration. It sailed through nine sheets of plywood and stopped on the tenth. Here’s the recovered bullet from that one. It looks like, rather than expanding outward, the hollow tip collapsed in on itself.

The other two .357s — the Hornady LeverEvolution and the 180-grain Federal hollow point — both expanded and made it through five sheets of plywood.

The .44 Magnum performance was pretty straightforward. All five loads expanded and all five loads penetrated seven sheets of plywood. It would be really interesting to see what the .44 version of that Barnes VOR-TX load would do in this test. Unfortunately, we did not have any on hand at the time.

I think it’s probably safe to assume that if any of these .44s had not expanded, they would have penetrated at least nine sheets of plywood like the Barnes did. Even though the best performer on this test was a .357, I would not want to suggest that .357 Magnum generally has better hard barrier performance than .44 Magnum. For the bullets that opened up, clearly the .44s penetrated better.

So Which One is Better?

If you had to decide between these two cartridges based only on external and terminal ballistics, it looks like .44 Magnum has a slight edge. But honestly, it’s not as much of an edge as I had expected. The only metric where .44 really blows .357 out of the water is energy. At the muzzle, our most energetic .357 would need about 33% more energy to be on par with the best of the .44s.

But the energy numbers alone don’t really tell us anything. The .44s did a little better than the .357s in the plywood and gel tests, but the difference was not as striking as the energy figures might suggest. It’s all about how that energy is being used.

These bullets use some of their energy to travel from the muzzle to the target. Then whatever is left over can either be used to crush a small hole that goes really deep, or they can expand and make a bigger hole that doesn’t go quite as deep.

Typically, that’s pretty much all handgun bullets can do. They make holes. So if you want to humanely take that deer, or you need to stop that Soviet paratrooper that just landed in your backyard, you’d better hit some vital organs directly.

On the other hand, true high velocity rifle cartridges can hit hard enough that, for a medium sized mammal like a human or a deer, the tissue around the wound channel stretches beyond its elastic limit. That causes tearing and bleeding and all kinds of trauma besides simply making a hole. Sometimes that will happen with a handgun bullet, but it’s not the norm.

Unfortunately, this effect doesn’t show up in our gel tests. The Clear Ballistics synthetic gel is too elastic to give us an accurate picture of what’s going on there. According to the wound ballistics experts, the velocity threshold where the temporary cavity starts to reliably cause wound trauma is thought to be somewhere around 2200-2500 feet per second. It depends on bullet design and what part of the anatomy is affected and some other factors. And a similar effect can take place at lower velocities with very large projectiles like a 12 gauge slug.

Fired from a lever action, .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum are moving pretty fast. They’re not really in the realm of typical handgun ballistics anymore. But they’re also not quite into true rifle territory. They’re kind of in between. They might cause some of those secondary wounding effects, but there’s no guarantee. This grey area is where .44 Magnum could have an even further advantage over .357 Magnum that is really hard for us to test or demonstrate outside of anecdotal evidence.

That is all a very long-winded way to say that if I had to choose between a .44 and a .357 lever action, I don’t see any reason not to choose the .44 if the primary purpose is hunting or self-defense.

Ballistic Superiority Isn’t Everything

But like I touched on in the intro to this series, most of us like lever actions for reasons that are not purely practical. These are fun guns that might sometimes be used in a practical role. So there are plenty of factors to consider besides ballistics.

If you want to put a whole lot of ammo through a lever action, it might make more sense to go with a .357 Magnum. When we’re not in a crazy ammo market like we’ve got currently, .357 is a little more affordable than .44 and it tends to be more commonly available.

Of course, you can also shoot .38 Specials out of a .357 or .44 Specials out of the .44 Magnum. Either way, the Specials can help you save a few bucks on ammo costs. They’re also convenient if you want to shoot these guns with a suppressor since most .38 and .44 Special loads are subsonic.

Depending on who’s going to be shooting the gun, recoil might be another thing to think about. With both of the Henry X Models, recoil was very sedate, even when shooting magnum loads. However, the .44 Magnums did have a little bit of a nudge that was not as noticeable with the .357s.

Personally, I found it a little more satisfying, in a way, to feel the recoil from the .44s. And they seem to hit the steel targets with a little more of a thump. But if you’ve got younger kids who are going to shoot this rifle, or someone who’s very sensitive to recoil or noise, you might want to lean more toward the .357. Yes, you could always get the .44 Magnum and have them shoot .44 Specials and that’ll take care of the recoil issue. But when you’re not shooting suppressed, I think it’s more fun to run these rifles with Magnum loads. In my experience, the magnums tend to be more accurate and you can get a little more range out of them.

That’s all kind of splitting hairs, though. I know it’s cliché to say it, but you really can’t go wrong with either one. Both .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum are a ton of fun with a lever action. With most rifles that are offered in both cartridges, you’ll get the same ammo capacity — both the Henrys have a seven-shot tube. With either of the magnums, you’ll pay a lot less for the ammo than you would for .30-30 or any other rifle cartridge you can feed a lever action. If you still can’t decide, just flip a coin because they’re both awesome.