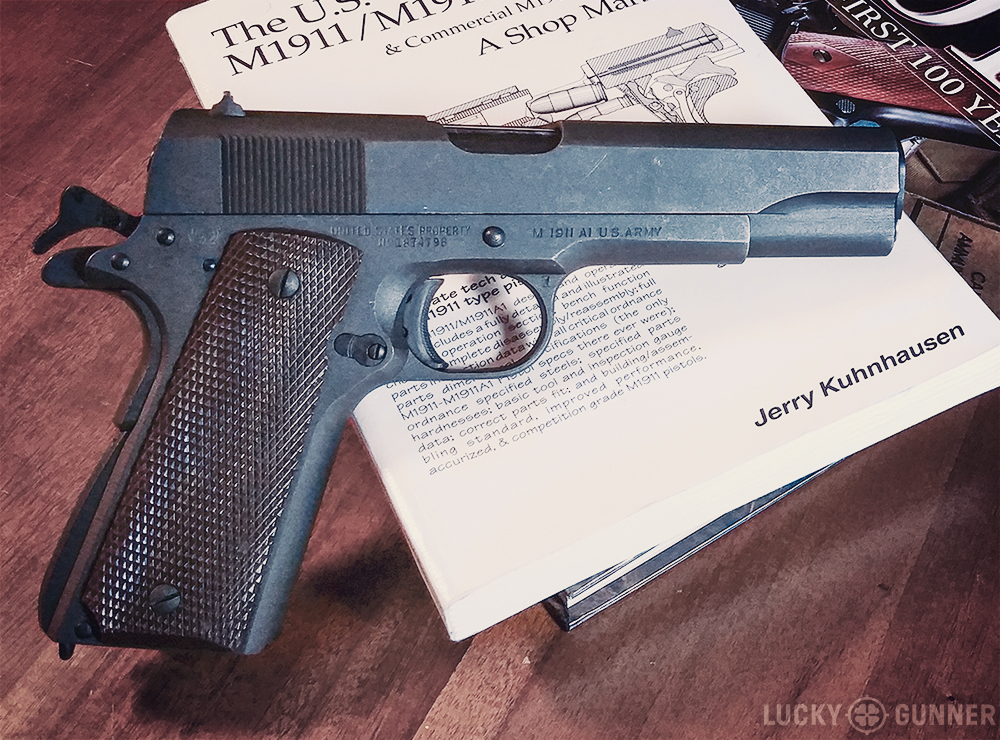

With a history of over 100 years behind it, the 1911 is as iconic now as it was when it set the standard for semi-automatic pistols years ago. For some, it still sets the standard today.

I have a special place in my heart for the 1911. It was the first gun I ever bought and carried. Over the years I’ve owned somewhere around twenty 1911s from Para, Llama, and Springfield to Les Baer, Wilson Combat, and Nighthawk Custom. There were also a few Kimbers and Colts thrown in for good measure, as well as many sizes and calibers.

I have more books about 1911s than I do about cooking, which may or may not tell you something about my cooking. It is the gun I’ve played around with the most, and it is the gun that I have both loved and hated in the extreme.

You can’t journey far down the road of handgun shooting without becoming aware of this model, and many people find themselves compelled to try at least one.

The talk across gun counters, volleyed around the internet, and shared at gun ranges will keep the 1911 relevant for another 100 years, but before you dive in, there are some things you should know about our beloved John Mosses Browning’s design.

The Good:

There are a lot of things to love about the 1911 that drive consumers to them and keep fans loyal.

Accuracy

Most guns will out-shoot their operators, but there’s something to be said about a well-manufactured 1911. Whether or not it can be classified as the most accurate production firearm is an ambitious claim, and obviously debatable. However, there’s something about the short, light trigger, the comfortable weight, and long sight radius that seems to bring the best out of its shooters.

The 1911 Trigger

If you haven’t heard the phrase “Nothing beats a 1911 trigger,” you probably haven’t been around the gun community long. Lots and lots of people love this trigger. However, it has some new competition due to the advances in trigger technology as well as individual shooter preferences.

The triggers on most standard 1911s are described as “crisp,” “light,” or “sweet.” The break—the moment the sear releases the hammer to fire the gun—is often described as breaking a glass rod. It’s clean, immediate, and distinct. There is very little excess movement or over-travel (the distance from the break to where the trigger can no longer move rearward), the reset can be measured in millimeters, and depending on make, model, and custom work, the amount of pressure required to take a shot can be as little as 2-4 pounds. This may seem dangerously light to some, but to many competition shooters, it’s Goldilocks.

Safeties (if that’s your thing)

The 1911, as designed by John Mosses Browning, has several safety features. Two of those safeties—the thumb safety and the grip safety—require active disengagement. In the 1930s, Colt dabbled with a third safety; a firing pin block that was activated by the grip safety. They quickly abandoned the concept but resurrected it with the trigger-activated series 80 firing pin block in ‘83. Other 1911 manufacturers use variants of one or the other, and some leave it out completely.

Customizable / Aftermarket

The 1911 parts aftermarket has no rival in the handgun world…yet. There are very few firearms with as much customization available. Some things like grip panels and sights can be changed in your living room, and, with a little willingness to learn, an ambitious person could potentially build a 1911 from spare parts.

There are extended slide stops (or releases, depending on your preferred nomenclature), high or low profile and ambidextrous thumb safeties. Guide rods can be general issue or full length. Mainspring housings can be textured, bobbed, or decorated, or they include a magazine well. Beaver tails can be short, long, or anything in between while triggers can be skeletonized, short, long, flat or any variation in between. Hammers can be Commander, flat, or spurred. The opportunities to customize are nearly endless. And that’s not even getting into the finishes.

Wide Variety of makes / sizes / calibers / materials

The first 1911 to roll off the production line 104 years ago had a five-inch barrel and a standard magazine capacity of seven cartridges. It was chambered in .45 ACP and made of steel. Over the years, grips and barrels have shortened to meet the demand for lighter and more compact carry guns. For the competitor or enthusiast out there, long-slide variants were also created. Frames can be found in a variety of alloys and polymers to shed weight, and 1911s can be found in calibers ranging from .22LR to the .50GI.

The Bad

It’s not all sunshine and roses for the 1911, however. It has its downsides.

Cost

Low end 1911s like Rock Island and Girsan will still set you back $300 or more. Many production model Wilson Combats start north of three grand, but your average 1911 will cost between $700 and $1,000 if you aren’t looking for too many bells and whistles. This is a stark contrast compared to the price of other modern service pistols.

Safeties (if that’s not your thing)

Not everyone appreciates the existence of the external safety. Some argue that the external safety features can be missed in a critical self-defense moment, rendering a gun useless when it’s most needed. 1911 aficionados largely purport this as a training issue, and there’s little evidence to back up either claim, so the war will rage on.

Capacity

Let’s face it, for the size and weight of guns these days, a standard capacity of seven or eight cartridges in a full or midsize gun is a little yesteryear. Sure, there are double-stack 1911s that have capacities that rival their high-capacity competition, but they are not as easy to find as their single-stack sisters, cost-prohibitive, and don’t necessarily have a reputation for reliability.

Weight

A steel, single-stack 4-inch 1911 is almost a pound heavier than any single-stack polymer-framed gun and still a few ounces heavier than a fully-loaded Glock 19. While that doesn’t seem like much on the surface, when carrying it around, those pounds can start to feel a little heavy, particularly when you consider the fact that you’re carrying half the ammo of a Glock 19 for the same weight.

Some people find comfort in the weight of steel. Others find it to be a negative trade off.

Too Much Of A Good Thing

There is such a thing as too much of a good thing, and that is certainly the case with the 1911. With around twenty manufacturers producing some variant of the 1911 (not including the small custom shops like Volkmann or Heirloom Precision), it should be no surprise to anyone that the market is saturated with options, and not all of them are good.

The $300 GI model you picked up on the cheap will likely not shoot like a $4,000 Wilson Combat. That they can both be called 1911s, however, sets naïve consumers up for a rude awakening regarding quality control and expectations.

Those who experience poorly made 1911s tend to paint the model with the broad brush of disappointment, not taking into account the inequality of the market. Others, who get a taste of quality-built guns but recoil at the price, search in vain to get their fix with lesser substitutes or put off buying their dream gun altogether.

In addition to the range of manufacturers and quality is the range of features and options. One can choose options like length of barrel or frame, the type of beaver tail and grip safety, the shape and features of a mainspring housing, the type of sights and hammer, and whether or not the frame has a rail. All these options can be overwhelming, leaving the indecisive buyer stuck and confused, possibly even purchasing a firearm that doesn’t suit their needs.

And that’s not even going into magazine choices.

The Ugly

Finally, we come to the ugly parts of the 1911. Well, most 1911s are beautiful, but from time to time, opinions and bad experiences can taint their image and leave them with a stain not easily rubbed off.

Reputation of the 1911

1911s have a reputation of being picky guns. If you talk to any true JMB-disciple who’s owned multiple 1911s through the years, he’s probably run across more than a few who were problem children. Out of the twenty or so 1911s I’ve owned, at least four have been malfunction-heavy to the point where they were moved along rather quickly. A few more were finicky when it came to ammo or needing to be cleaned after so many rounds, and the rest ran as reliably as you would expect a firearm to run. Some shooters have had better results than mine. Others report far worse.

Either way, for the price, many feel the uncertainty of quality makes them an unnecessary risk.

This questionable quality is largely driven by the wide variety of manufacturers and the wide range of quality control and cost-cutting measures. Even well-known and reputable companies have taken short-cuts that have resulted in problematic guns and damaged reputations.

Most gun manufacturers these days will stand behind their products enough to guarantee a working product, eventually. Some shooters wonder if it’s worth the time and effort.

Home Gunsmithing and the Used Market

Thankfully, Frankenguns are becoming more rare, but when they are found they tend to be 1911s. The accessibility of aftermarket parts and Dremel tools makes them almost irresistible to tinkerers and fantasy gunsmiths.

One of my favorite guns is a 4.1” Wilson Combat Professional in .45 ACP that my husband bought used for me in a screaming deal back in 2007. In the eight years I’ve owned, carried, and shot that gun I can remember only a single failure to extract that happened somewhere in 2008. The time spent with it at the range or in training classes can be expected to be trouble-free and enjoyable. The gun simply runs and I’d trust it with my life—and have. That experience has been replicated with our used $450 Springfield Armory pre-2001 Loaded Model. Point being, when they run, they are some of the most fun and easiest shooting guns you’ll ever run across.

When they don’t, however, you kind of just want to throw it out the window, but then you might hurt the resale value.

Good article…THANKS!!

Yup. Buy quality. Feed it good ammo. Don’t screw with it….

… best left alone right out of the box … and you get what you pay for.

I heard the Rock Island 1911’s were good guns? I get the feeling you don’t think so, what about that?

What you don’t get with Rock Island, is a premium finish. Kinda thin and uneven. But I have my two as carry pistols, and soon a third will join the stable. A finish while it can be beautiful is wasted on a EDC. Just my not so humble opinion. I’ve got a couple thousand rounds downrange with my first, never a single problem. I’ve got 368 downrange with the second. A couple a magazine related hic-cups so far. I’ll work those out shortly. The fit and performance is every bit as good as those that cost double the dollar. YMMV

The Barrel bushing also breaks off of the factory made Rock Islands after about 5 rounds since the bushing is only made of aluminum.

To add a bit of info on Rock Island 1911`s, the slides are the weak point and the frames are the second weak point. Search on the failures of Rock Island 1911`s. Aside from the frame steel being weak, the end of the slide where the spring/bushing are held in place, the slide has been known to crack due to inferior metal and manufacturing techniques. Bottom line you get what you pay for. The higher quality 1911`s are made from better steel using better manufacturing methods. Just look at the list at Clark`s custom guns, the list of manufacturers that avail themselves to the 460 Rowland conversion system. Better yet call them for a complete list, I called and along with those listed on the website, Ruger, Sig Sauer are suited for the conversion for superior metal used in manufacturing. They warn that any 1911 made in the Phillipine`s is to be avoided when it comes to conversion to the 460 Rowand conversion. The 460 Rowland turns a 45acp into basically a 44 magnum in a 1911 frame.

The Backwoods, I fail to agree with your opinion on the Armscor guns. I own 5 and they

shoot as well as my Ruger 1911s. No problems with the slides or frames. And, Armscor does use quality steel in their 1911s. With the number of 1911s they sell, they would be fools to use inferior materials. You are entitled to your opinion and I will fight to the death to protect that right. But in my humble opinion, Your facts are lacking in documentation.

We are all entitled to our opinions, I have seen in several articles where the frame and slide metal were made from inferior metal and one case of the bushing end of the slide broke completely off. The machines the Armscor pistols are made on are original machines that made the 1911 back before WW2. Inferior metal or like the 1903 Springfield`s with a lower than an 800,000 serial number made by Springfield Armory, they are prone to receiver failure due to not being heat treated correctly. I have one and as much as I would love to shoot it. I will not because I do not like the idea of the bolt going through my right eye.

thebackwoods, sorry you are so set in your opinion of Armscor. Seems that the gun magazines would have pointed this out in their reviews. Even GunBlast blog

gives good ratings on Armscor guns. Thankfully your beliefs will not affect Armscor’s reputation.

I intend to upgrade one of mine to the 460 Rowland set up for hunting, this conversion, if you have never heard of it, basically more than doubles the energy of the projectile when fired and uses stronger recoil springs and a compensator to help tame recoil and frame battering with this high energy round. The only 2 things different in the 45acp round and 460 Rowland s the brass is approximately .100 inch longer for the Rowland to keep it from chambering in a 45acp. and the powder charge. I can use the same dies with the only adjustment is the powder drop/case mouth expander needing t be raised .100 to allow for the longer case.

Is there something Gunblast *doesn’t* give good ratings for?

The Rock Island is by far THE worst 1911. I fired 8 of them and each one jammed every other round. The Colt or Springfield are the 1911’s you wanna get. You can tip a cow over with a colt at about 1,500 feet.

I did a lot of research before I ordered my first 1911 today. I’ve studied the testing results and blogs, etc. I do have an airsoft reproduction of the Colt 1911 100th anniversary edition. It is the same size and weight as the real gun I just bought. If you have small hands, you can still handle a 1911 as the grip is slim enough so that you can reach the trigger easily.

This was a great article. I’ll print it off and add it to my other articles about the 1911. Thanks for the great info.

@annwendt:disqus

I hope you are happy with your new gun. To me, there’s nothing like a new gun to make your day! My wife loves the 1911 she got for Christmas, and it seldom leaves her side. In fact, our computers are next to each other and I could reach out right now and touch it.

Enjoy!

I’ve owned and shot a great many 1911s. Qualified Expert with one back in the day in the army. Love them and still own two. But for a reliable, EDC, I’ll stick to my Glock.

Very nice rticle,,I have owned my Ruger SR1911 for almost a year now,,after 1000 rds not a single hiccup.There is just something about the way the fit in the hand that reminds me of my favorite coffee cup. And maybe its just the history of it that puts that smile on ones face when to put that big ole 45acp rd down range.stay safe everyone, Till next

I’ve only fired about 500 rounds through my Springfield 1911 A1 Mil Spec model and have been very impressed with it. Put some Hogue one piece grips on it and like it even more. Not as much as a burp so far. It’s my first 1911.

This is just as vague as every other opinion about guns, let alone 1911’s. you could put the exact same report for every category/model of gun out there. When is somebody gonna actually make a top 10 or 5 actual cheap gun list that works prfectly for at least 10 years right out of the box? Every gun has a cheaper version, and some of those are just as good quality as the most expensive. So where is the “real” good, bad, and ugly list? Top quality for cheap price #1 and on down! Not another vague or general description of everything out there telling you good luck in your random picking that will most likely be a waste of your time and $$!

I think part of the problem is that it would be really hard to actually determine what the list should be. X brand with Y ammo in Z barrel length may be perfectly reliable, but changing one of those variables could result in a completely different experience. And there are definitely more than just 3 variables at work here.

No, Melody did not create a definitive list of good, bad, and/or ugly 1911’s. But that wasn’t what she set out to do. She set out to provide “some things you should know” (her words from paragraph 5) before diving into the world of 1911’s. She highlighted the good, bad, and ugly features/traits of the 1911 platform so that people not already familiar with that info would have a starting place for 1) determining if they are interested in a 1911, and 2) evaluating some of the versions out there.

Look for 1911`s that are candidates for the 460 Rowland conversion package, the website lists 4-5 manufacturers and if you call the will give you more information as Sig Sauer and Ruger are on the list also. The 460 Rowland conversion gives 44 magnum performance out of a 1911 frame.

Well I like the Colt gold cup national match little more money but good gun

Good summary Melody. I think each manufacturer should tell you how to polish the feed ramp, oil the rails every few months and finally, make sure your 45 is clean so you have total reliability. I learned to polish the feed ramp as an example and honestly, spending money on a custom 45 isn’t for everyone. So I would like to hear from you about how you take care of your 45 in general. It’s an amazing pistol, my go to, most accurate and finally, 45 means stopping power. Support the 2ndp amendment…thanks

Stopping power huh?

Absolutely! the Pistol Ball Caliber .45 1911 can punch down a horse at 1,000 yards knocking it 10 feet backwards!

I have gone back into owning a 1911 after a 30 or so year hiatus. My 1st was a used Colt Combat Commander. It preformed well since the previous owner worked all the bugs out. In those days Colt 1911s had, IMHO, and just about every gun magazine ( the readable kind) the reputation of being the new gun you had to fix. I recently picked up a new ATI 1911 Military. Very sweet gun for the price, $349.95. A very amazing trigger.

Totally agree with you on the ATI, Keith. My wife wanted a 1911 for Christmas, so we got an ATI 1911 Military. Really a nice gun. Accurate, smooth, and a great trigger. I’ve also got an ATI Commander tactical model with the usual upgrades. Great gun too, but not quite as smooth as hers.

Great article. I love the 1911 for all the reasons stated above (trigger most of all). My Springfield runs flawlessly with the factory mags and any ammo I want to feed it. I don’t carry it because of the relatively low capacity and hefty weight, but I would never consider getting rid of it. It’s the gun I take to the range if I want to “shoot for fun!”

Good article about a great gun. I’ve never met a 1911, or any other semi auto, that couldn’t be made better for me by a competent Gunsmith. I might own some polymer pistols but my favorite and most accurate handgun is a steel 1911 from Clarks Customs in .45 acp. If your shot goes where you pointed it, how many rounds do you need?

@1X@1XRayMan1:disqus

I agree with you, but blanket comments like that are risky. Putting your shot where you’re pointing depends on whether or not your target is standing still waiting for it, whether you’re standing still on the range or moving, how much time you have to make the shot, and whether the target is shooting back at you.

Whats wrong with Girsan and Rock Island?

ignore this question, forgot I had asked it before!

The barrel bushing on most Rock Islands snap off after about 5 rounds due to the fact that they are only made of metal.

Great article. My first handgun (long ago) was a Ruger Security Six revolver, but my second was an Argentine Erjicito 1911, and it was a great gun. Of course, I had a friend who told me we needed to tweek this spring or that one, until he’d buggered it up to the point it wasn’t reliable for more than 2 -3 rounds.

I sold it.

Since then, I’ve had a number of 1911s, and my wife and I currently own two. Her GI model is her go-to carry gun and her fave at the range. My Commander Tactical is a fun gun, but I prefer others for EDC. I also carried a Kimber Combat model for almost two years in Iraq, thoughtfully provided by my employer for a DoD contract. It was smooth and reliable. Flawless, in fact.

But, these days my EDC is a G21. I still love the .45 ACP cartridge, but I prefer the flawless reliability and 13+1 capacity of the Glock. I own two G21s and they are both flawless performers no matter what ammo I am feeding them.

But, my wife, who asked for her 1911 Government model for Christmas, utterly delights in it and I am glad. And yes, she can shoot it very well. A 1911 is a brutal gun, and she understands that you have to be brutal and aggressive when you shoot it.

I own 4 Ruger SR1911s, 1 Remington R1 and 5 Armscor 1911s. Considering the difference in

price between the three. I have had no problems with any of them. Of course the first thing I do upon

returning from the range is cleaning the firearms, every time. Even before sitting down in front of the TV

with a Budweiser. If I fire a shot at a feral hog, the gun gets cleaned. A pain in the butt maybe, but

that is my thing. Seems to be working!

Agree completely on the cleaning. Personally, cleaning my guns is a sort of Zen experience. I always clean my 1911s as soon as i get home, as well as some of the others like my Jericho. The Glocks and Beretta 92s can go longer without cleaning becoming an issue for reliability, but they still get cleaned monthly.

Gotta rub your guns every day not monthly to reduce malfunction.

I have a model 70 Colt 1911 45acp and I love it. Yes, it is used but was well taken care of. Heavier than the Glock sure, but that’s what I love about it. I have 8 shot clips and works just fine and I know if I ever had to use it, they will drop. I buy the best ammo because even for target practice I don’t want my gun clogged up with crap. Have a 38 6 shot pistol I buy a little lower grade ammo for, as it’s easier to clean. However I am thinking of buying a smaller 9 that may be a Glock or Ruger.

Good article!

Although I have carried a number of pistols, I always seem to gravitate back to the 1911, of which I own a few. My current EDC, A Rock Island Armory 1911A1 FS Tactical, has had a few adjustments along the way, but it runs flawless and is highly dependable. As is said in biker circles, “Chrome don’t get you home!” so I don’t feel bad about carrying a pistol that looks a little worn for wear. The EDC is lovingly cared for and even ugly guns need to be loved.

The 1911 is the most perfect pistol ever created. The only disadvantage is the pressured recoil spring.

Back in 72 I had a 1911 9mm Spanish made by Star. Quite some history with the company and Franco supporting Hitler and these were sent to the German front lines in WW II. But, I had one and like most great firearms I had decades ago, a Nam Era.45 I just traded or sold them, dumb. Now, I’m really tired of Striker Fire Pistols. So I’m getting another 9mm 1911. Just can’t seem to part with over a grand being retired. Thinking of ATI, Rock Island or Citadel???? Difficult decision. However, maybe a used upper end firearm? Just afraid of inheriting someone’s problem?