Since it first debuted in 1983, 10mm Auto has dominated the handgun scene as the ballistic equivalent of the mighty hammer of Thor. At least that’s what one might think from listening to some of the caliber’s more zealous advocates. But now you can see for yourself how it stacks up to other handgun calibers since we recently added several 10mm loads to our ongoing ballistic gelatin testing project.

As always, I have tried to refrain from tainting the test results post with too much of my own opinion and commentary. But after considering what we saw in the gel tests, I wanted to offer a few thoughts about the suitability of 10mm in a self-defense role. Watch the video below, or scroll down to read the full transcript.

Last week, we published the results of our 10mm ballistic gelatin tests. You can see the full results and details on the post at Lucky Gunner Labs. Today, I want to dig into those results a little bit and I also want to tackle the broader question of whether or not 10mm is a good choice for self-defense.

10mm Gel Test Performance

The gel tests show us what kind of penetration and expansion to expect from a bullet in soft tissue. 12-18 inches is the penetration standard that’s been used by the FBI for years and any duty ammo that has a good track record in actual shootings typically will meet that standard. Expansion is not as important as penetration, but we like to see the bullet expand at least 1.5 times its original diameter which is .6 inches in the case of 10mm Auto.

Out of the eleven 10mm loads we tested, five of them met both of those criteria. And if we allow for a little bit of over-penetration, there are two additional loads that make the cut. Seven out of eleven isn’t bad at all. And it’s really seven out of ten because one of those loads was a non-expanding full metal jacket. So, finding 10mm ammo with good terminal ballistic performance should not be a problem at all. If that’s the only thing we’re looking at, it’s a solid choice.

10mm Auto Disadvantages

One of the major disadvantages of this caliber is that there aren’t many 10mm pistols to choose from. With a just a couple of exceptions, the options are limited to the kind of large-frame full size pistols that are usually chambered for .45 ACP. So that’s kind of a drag if your hands are small or if you plan on carrying this thing around. Any other significant criticism I can come up with for 10mm could just as easily apply to 40 or 45. Practice ammo costs more than 9mm, but it’s come down a lot in the last few years and it’s usually priced pretty close to 40 or 45 FMJ. Ammo capacity is typically one or two rounds greater than the same gun chambered for 45. Recoil is kinda snappy, but not really that bad in a full size gun. Except for the really high velocity loads it feels basically like shooting a .45 or maybe a pocket-size 9mm.

10mm Auto versus .40 S&W

So that brings us back around to the issue of ballistics. If we’re going to seriously consider 10mm for personal protection, we have to ask what it’s bringing to the table that we can’t get out of one of these other calibers. Let’s take a closer look at these gel test results and compare them to some of our previous tests. I’m going to focus on .40 S&W because it’s got a history linked to 10mm. Back in the early 90s, .40 S&W started out as just a weaker version of 10mm, but there have been major advancements in bullet technology since then and modern 40 caliber loads have a reputation for excellent street performance. The ammo companies haven’t put nearly as much effort into improving 10mm over the years. A lot of today’s 10mm factory loads actually use the same bullets with the same velocities as .40 S&W loads. But that’s not always the case.

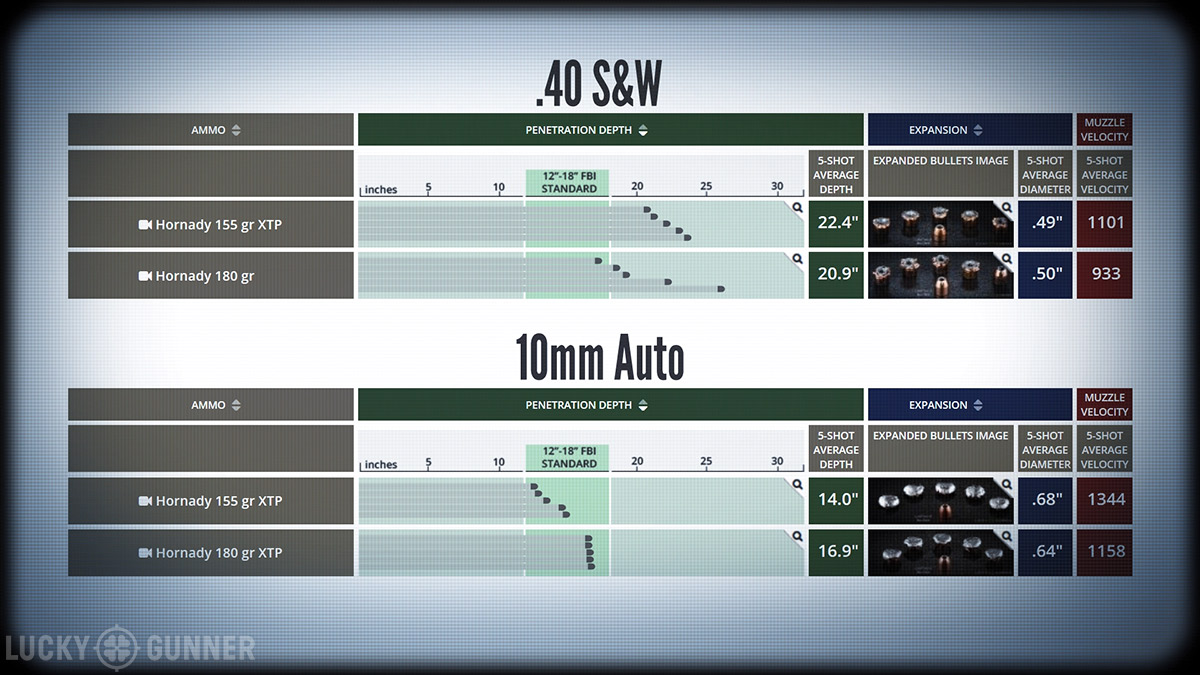

The Hornady XTP loads are good examples. Compared to their .40 S&W counterparts, the 155 and 180 grain XTPs both have 20% more velocity in 10mm. Now to be fair, when we did our .40 S&W tests, we used a Glock 27 with a 3.4-inch barrel. Our Glock 20 10mm test gun has a 4.6-inch barrel, so this isn’t exactly an apples to apples comparison. If we added an inch to the Glock 27 barrel, we’d expect to see the velocity go up by about 30 to 80 feet per second, which would still be much slower than the 10mm loads. Using the data we do have, the XTP bullets seem to perform much better at the 10mm velocities. We get better expansion and none of the over-penetration that we see with the 40s.

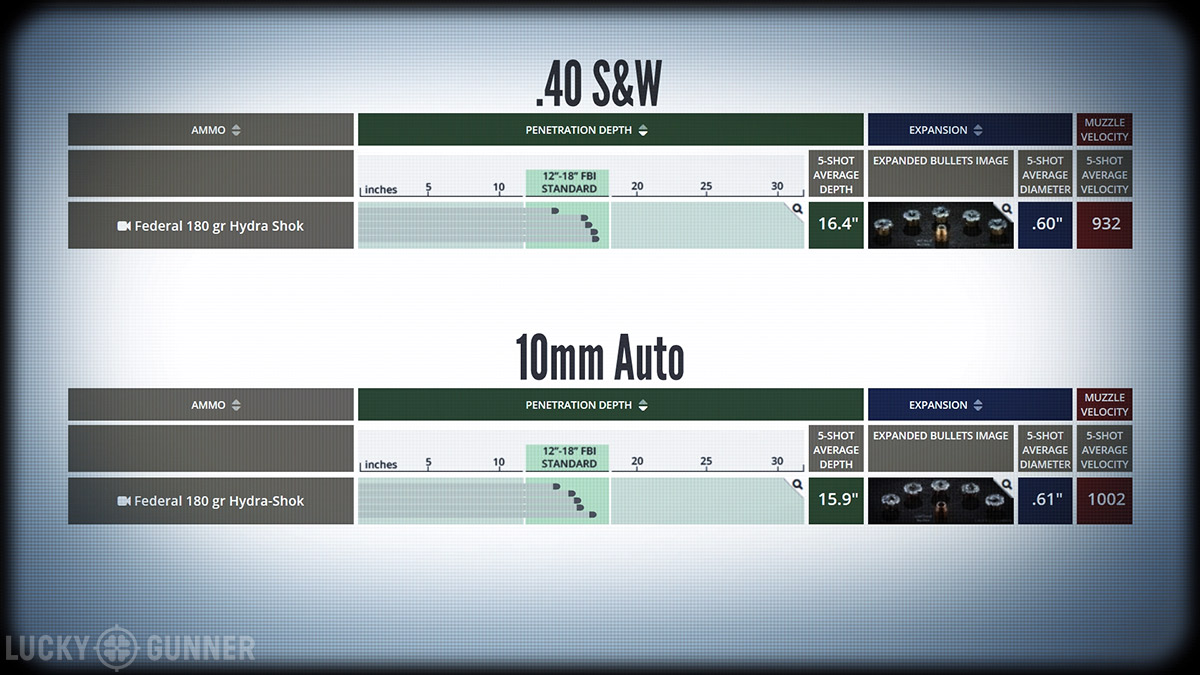

The 180 grain Federal Hydra-Shok is also loaded in both calibers, but there is only a 7.5% velocity increase in 10mm. From a ballistics standpoint, these two loads are essentially the same thing. Penetration is right around 16 inches and the expanded diameter is about .60 inches for both loads. This is ideal performance in gelatin for self-defense ammo.

So, pushing a 40 caliber bullet to higher velocities sometimes results in better terminal ballistics, but that is entirely dependent on the bullet design. If we look at the best 10mm loads and the best 40 S&W loads, there’s not really any difference in the test results. If they weren’t labeled and we didn’t show the velocity, you would have no idea which ones came from a .40 and which ones came from a 10mm.

Velocity, Bears, and Bad Science

I’m not saying that .40 S&W is necessarily just as powerful as 10mm. But it’s pretty clear that a .40 caliber bullet does not have to be pushed to maximum 10mm velocities in order to do what we want a self-defense round to do. So why would we need that extra velocity? Well, first of all, the target might not be a human. 10mm is gaining some ground as a caliber for hunting medium to large game or for protection against dangerous animals. That context is not one I am really qualified to comment on a whole lot, but I think it’s safe to say that if you have to shoot a bear, you’re going to want more than 12-18 inches of penetration. A non-expanding high velocity 10mm is going to penetrate as well or better than any other common semi-auto caliber. Is that enough to punch through the skull of a charging grizzly? I have no idea, but if you find out, let me know about it.

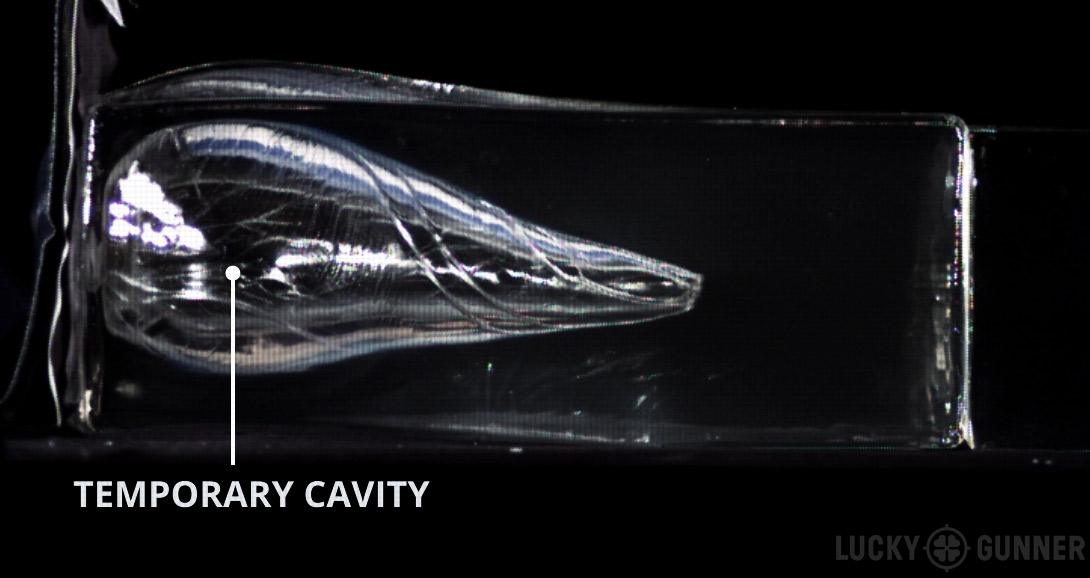

Another reason some people seem to want that extra velocity is because more velocity means more kinetic energy transfer. If we’re looking at two loads that have similar penetration and expansion in gel, a lot of people believe the muzzle energy tells us which one would actually cause a more severe wound. They will often point to the temporary wound cavity as evidence. That is the sudden opening that’s created in tissue or in gelatin when the bullet impacts. Sometimes, that temporary cavity can cause tissue to tear, which creates wound trauma even if that tissue was never actually touched by the bullet

But, according to wound ballistics researchers, this rarely happens when people are shot with handguns. It tends to happen more often with rifle bullets because they’re traveling much faster, but with handguns, the temporary cavity is, at best, an unreliable secondary contributor to incapacitation. Looking at the research from the last few decades, there doesn’t seem to be any proven correlation between muzzle energy and bullet effectiveness.

In the case of 10mm, more velocity might get us more penetration, and, like I said, that could be useful for outdoor applications. For everyday protection from violent human attackers, the super high velocity loads are just not necessary and might even be a liability in an urban environment. As always, shot placement is king, and you need to be able to place those shots in a hurry. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with relying on a larger caliber like 10mm if you can meet some objective performance standards first, like the 5×5 Drill or the Super Test, both of which we have featured in our Start Shooting Better series. If those are a struggle for you with a 10mm, then you might need more practice or to switch to a more manageable pistol.

Looks like Hornady 180 gr. XTP is the most consistent. Isn’t that the overall point of a self-defensive round? (when talking about the two legged kind of threat)

Never shot a bear, but I was forced to dispatch a giant rabid raccoon that was blind and simply locating potential prey by sound. It was super freaky as it tried to follow me around. A single 10mm bullet fired from a Smith&Wesson pistol split its head wide open. End of story.

I would hope that near any standard pistol or revolver calibers would be effective on raccoons. Even a 22WMR would probably work well.

I never had an opportunity to fire a 10mm so I’ll have buy one but ..

I love my 40 cals and can put 16 head shots with a 2 inch spread at 40 yards but I think I’d just run from a bear and hope who ever was with me was running slower …

I call “BS” on this one.

I second that!

40 yards is pretty far, but I have heard some military guys can do superhuman feats with pistols. They get to shoot hundreds of rounds a day, day after day, and get paid to do it.

Wow, you’re the spitting image of Milo. How weird is that?

Liberals hate me for the way I look

The 10mm is more than adequate for self defense. I have killed two elk with mine and a pile of deer during our short range weapon season. The first elk was with the old 200gr. Speer gold dot and the second one was with a 200 gr hard cast both of these were on top of 10.6 gn. of blue dot @ 1200 fps and both were one shot kills that went less than 20 yds. after being hit !!