As a Navy Corpsman, I had the opportunity to see the results of a number of injuries, including those involving the face and eyes. I was astounded to see how crucial eye protection, sometimes referred to as “eye pro,” was and how effective it could be. I saw a number of potentially vision-threatening fragments of metal and other debris stopped by good eye protection. In one case, a large chunk of metal hit a Marine in the face, partially penetrating the lens of his glasses and causing him to lose vision in that eye. Without that eye protection, he most likely would have been killed.

Not all eye pro is created equal, though. In order to understand how one type of eye protection might be “better” than another, we need to first look at what standards various types of eyewear may meet – and then shoot at them to see which eyewear provides the best protection.

Eye Protection Review Summary

This post is pretty long. If you’re short on time, here’s a brief video summary. Also, the “Summary and Recommendations” section at the end of the article will help you understand what to look for when buying shooting glasses.

Setting the Standard

Military and Industrial Standards for Eye Protection

Some organizations have set standards for eye protection – both ANSI, which sets industrial standards, and the US military, which has standards for what types of eye protection may be used by Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines on the battlefield and in training environments.

The basic ANSI standard is referred to as Z87, and you’ll see this marked in a number of locations on most eye protection marketed to shooters. However, the Z87 impact standard involves a .25″ steel ball traveling at 150fps – this is fine for protecting eyes from debris that might fall or be thrown at them, but is not extremely relevant to shooters, who are dealing with objects traveling at much higher velocities.

The military standards are much higher. MIL-PRF-31013 describes a .15″ diameter projectile of a unique design traveling at 650fps, which is much closer to the velocities that are seen in the shooting world. Not surprisingly, there are not many types of eye protection on the market which are tested to this standard – or, of those that are, not many are marketed as such.

There’s a separate military standard for goggles, involving a .22″ diameter projectile at 550fps. The military standard does call for a shape and material which would provide for more barrier penetration, however, the testing conducted for the purposes of this article significantly exceeds both military standards in terms of projectile mass and velocity.

Neither standard is perfect, but the military standard is far more stringent and difficult to pass than the industrial standard. I strongly recommend going beyond Z87-only eyewear for shooting purposes.

What We Tested

From Cheap to Expensive, Here’s The List

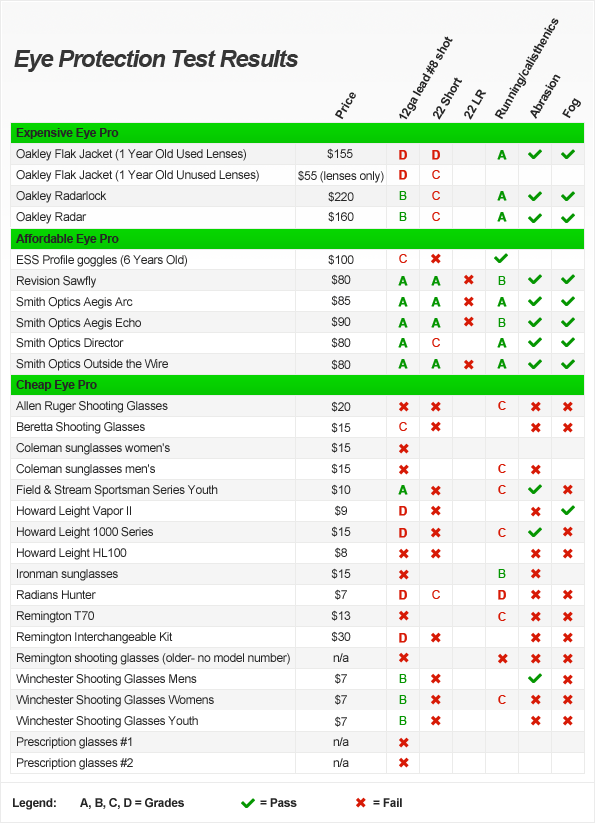

Over 25 types of eyewear were tested, from $6 eye protection made in China to $220 high-end sunglasses made in the USA. Here’s the list.

Expensive Eye Pro (over $100):

- Oakley Radarlock

- Oakley Radar

- Oakley Flak Jacket (1 Year Old Used Lenses)

- Oakley Flak Jacket (1 Year Old Unused Lenses)

- ESS Profile goggles (6 Years Old)

- Revision Sawfly

- Smith Optics Aegis Arc

- Smith Optics Aegis Echo

- Smith Optics Director

- Smith Optics Outside the Wire

- Allen Ruger Shooting Glasses

- Beretta Shooting Glasses

- Coleman sunglasses men’s

- Coleman sunglasses women’s

- Howard Leight Vapor II

- Howard Leight 1000 Series

- Howard Leight HL100

- Ironman sunglasses

- Field & Stream Sportsman Series Youth

- “Prescription glasses #1”

- “Prescription glasses #2”

- Remington T70

- Remington Interchangeable Kit

- Remington shooting glasses (older- no model number)

- Radians Hunter

- Winchester Shooting Glasses Mens

- Winchester Shooting Glasses Womens

- Winchester Shooting Glasses Youth

Although the testing is broken down by these price categories later in the article, I also singled out some eyewear as being absolutely unsuitable for eye protection.

It’s important to note that some of the eye protection tested was older and had been exposed to sunlight for significant periods of time. The implications of constantly using eyewear, especially that which is exposed to sunlight, will be explained in this article.

How We Tested It

How Different Types of Ballistic Eye Protection Stack Up

Initially, I planned on testing eye protection to both military and civilian standards. However, the decidedly non-standard materials and methods used for both made it pretty difficult to duplicate exactly what the military specifies, as well as what ANSI requires.

Therefore, I used a number of common firearms with relatively low-powered types of ammunition to determine how well each type of eye pro dealt with projectiles moving at “firearm velocities,” albeit those at the lower end of the range. These low-velocity projectiles might represent, for example, a ricocheted fragment of an originally larger and faster bullet.

It’s important to note that the ammunition you see here exceeds military and civilian testing standards. This test was harsh because we wanted to find the most protective eyewear on the market – and then we wanted to see when that “best eye pro” would fail.

Therefore, I introduced a few more powerful types of ammunition and used them on the eye pro which successfully protected the face from the slower/lighter ammo. All shots were taken from 25 feet. The types of ammunition used include:

- Federal 12 gauge 2 3/4″ #8 lead shot

- CCI .22 Short – 29gr/710fps

- CCI .22LR Standard Velocity – 40gr 1070fps

- Fog testing

- Abrasion testing

- Fit during athletic activity

Several interesting observations were made during the course of this testing. I’ll walk you through what I discovered as I tested eye protection and how my thoughts on the use of various types of eye pro have changed as a result.

Eye Protection Quick Reference Scorecard

Unsatisfactory Eye Pro

Three Types of Eyewear You Should Not Use As Eye Protection

In the course of my testing, I discovered that there were a few types of eyewear which should not be used as eye protection:

- impact rated eye pro which has been exposed to sunlight for long periods of time

- non-impact rated prescription glasses

- non-impact rated sunglasses

For the purposes of this article, consider the ANSI Z87 to be “impact rated.” It’s not perfect, but it’s better than a lot of stuff. For example, it’s my guess that a lot of people are using eyewear which falls into the above categories as eye protection.

First, we’ll take a look at older eyewear.

I tested several different types of eye protection that I had owned for five or more years – my issued ESS goggles, some yellow-lens shooting glasses which were clearly of a previous decades’ style, some prescription glasses that had an integrated headband and were intended for “sport” use, and another pair of shooting glasses that were fairly basic/inexpensive, but had seen use for years.

Every pair of older eye protection absolutely failed to stop basic “threats” which were stopped by comparable eye protection of newer manufacture or less use.

The highest quality example of the “older” group was the ESS goggle, which passed all military ballistic testing and which I personally wore in Iraq for almost all of 2006. ESS goggles and glasses were in use by nearly every Marine and Sailor in the area, and I constantly saw how effective they were.

Even so, age – and constant exposure to UV rays from sunlight – takes its toll on polycarbonate eye protection. For this reason, I would avoid using eye protection that is more than a few years old and/or has seen a lot of sunlight. Knowledgeable military sources informed me that the life cycle of military eye pro is expected to be six months.

If You Enjoy Vision, You Shouldn’t Use Regular Prescription Glasses As Eye Pro

I think it’s also important to discuss prescription glasses. A fair number of people, including myself, wear prescription glasses, and a lot of ranges don’t see any need for protective eyewear beyond prescription glasses. Wearing eye pro that fits over prescription glasses is cumbersome and annoying, to say the least, and for the most part I’ve simply worn my prescription glasses without thinking about how well they protect my eyes.

Then I shot a few pairs of prescription glasses, both glass and polycarbonate. Quite frankly, I will never wear regular prescription glasses as eye protection again. It is difficult to imagine how the glass prescription lenses could have been any worse – not only did they offer little resistance to the birdshot, but small glass shards flew in various directions after the shot, including straight back into the “eyes” of the styrofoam head.

The polycarbonate lenses didn’t shatter in the same dramatic manner, but they did crack and allow many pellets to go through.

I also tested a number of cheap, off-the-shelf sunglasses, and while some stopped birdshot, others did not. If it’s not ballistic rated/tested eyewear, you shouldn’t be using it for eye protection, in my opinion.

Cheap Eye Pro

Sometimes You Get What You Pay For

[galleria id=”72157630651852336″][/galleria]

Next – “cheap,” inexpensive eye protection. This is what you’re most likely going to encounter as rental or loaner eye protection at shooting ranges across the country. You’ll also find it for sale for ten to thirty dollars, depending on how many different colored lenses are included. Despite the fancy appearance of some of this eye protection, most – not all – are tested only to Z87 standards. You’re paying more for some that might be branded with a certain firearm manufacturer’s logo, not necessarily better protection.

That said, some of the most inexpensive eyewear tested was Winchester branded, and the packaging stated that it met not only Z87 standards, but MIL-PRF-31013 as well. So not all is lost when it comes to cheap eye protection. Although the Winchester eye pro didn’t perform as well as other, more expensive, MIL-PRF-31013 tested eye pro, it was much better than most other products in the price range.

Most of the eyewear in this range did not perform well in comparison to some other types. While many of the lenses themselves stood up to #8 lead shot in terms of not allowing penetration through the lens/lenses, almost none were able to stop either a glancing blow or a perpendicular hit from a .22 Short bullet, which more expensive eye protection did without fail.

If you’re looking for eye protection and don’t want to spend much money, my recommendations would be the Field & Stream Sportsman Series and the Winchester Shooting Glasses.

Affordable Eye Pro

Sometimes, Yes, You Get What You Pay For

[galleria id=”72157630651748290″][/galleria]

The eyewear in this price range is (or was, when it was produced) tested to both Z87 and MIL-PRF-31013 standards. Several of the items tested, such as the Smith Aegis and Revision Sawfly spectacles and the Smith Outside the Wire goggles, are on the Authorized Protective Eyewear List (APEL) of eyewear specifically authorized for use by US servicemembers while deployed.

The performance of all new production APEL eyewear was outstanding. Fort example, the Revision Sawfly eye pro successfully stopped #8 lead shot – which I found that most Z87-rated eyewear did – but it stayed together as a unit after being shot in that manner.

In addition, there was very little damage to the face and eye sockets/cheek areas.

The same Sawfly lens was then shot head-on with .22 Short – a 29 grain bullet traveling at 710fps, which is not powerful by modern firearm standards, but might be fairly representative of a ricocheted bullet fragment. It stopped this bullet, which was placed in the middle of the right side of the lens, with minimal damage to the cheek area.

I attempted this same feat with a 40gr .22LR bullet at 1080fps on the left side of the lens, but it did penetrate. The Revision eyewear is thus not exactly bulletproof, but it offered impressive levels of protection and performance.  Similar protection was offered by the Smith Optics eyewear. I was especially impressed with the performance of the Smith “Director” sunglasses, which were the only two-piece-lens sunglasses I tested which did not lose a lens when hit with birdshot.

Similar protection was offered by the Smith Optics eyewear. I was especially impressed with the performance of the Smith “Director” sunglasses, which were the only two-piece-lens sunglasses I tested which did not lose a lens when hit with birdshot.

However, they didn’t do as well when shot with .22 Short, stopping an angled shot but losing a lens back into the eye area when hit directly with .22 Short. Still, I would not hesitate to use this design as eye protection when shooting on the range.

The Smith Aegis eye pro – both the standard Aegis Arc and the Aegis Echo, which is intended for use with communication headsets, offered excellent protection against birdshot and .22 Short, with no penetration of the lens and minimal damage to the styrofoam face. The Smith Outside the Wire goggles stopped birdshot and .22 Short as well, but the additional cushioning provided by the goggle design resulted in almost no damage whatsoever to the face.

Most people aren’t going to wear goggles at the range, but for a deployed military member, goggles are an excellent option in terms of protecting the face and eyes. As mentioned above, the ESS goggles tested were fairly old and definitely past their life expectancy. While they certainly offered a high level of protection when new, they should serve as an example – switch out eyewear, or at least replace the lenses, before they stop being effective as eye pro.

As long as it was in new condition, I would recommend every type of eye protection listed in this section for shooting purposes. Deployed servicemembers should pay close attention to the APEL, which is a well-researched and tested list of eye protection.

Expensive Eye Pro

With High Prices Come High Quality or Style, But Not Necessarily High Levels of Protection.

[galleria id=”72157630651832460″][/galleria]

The most expensive eyewear in this test came from Oakley, and to be honest, I love Oakleys. In fact, the Flak Jackets with VR28 lenses I tested were my personal eye pro for the last year. I like the style of Oakleys, and how well they stay on my face when I run.

However, while most Oakleys are Z87 rated, they are not MIL-PRF-31013 rated. What does that mean? Well, that they aren’t as good at protecting your eyes from small, fast moving objects. The one piece lens Radar and Radarlock models offered acceptable protection from birdshot and stopped or deflected angled hits of .22 Short, but wouldn’t stop direct hits from .22 Short.

Would this keep me from using them as eye pro at the range? I’d definitely use them for a lot of athletic activities and wouldn’t feel too unsafe using them at the range, but I would not buy them specifically to use as protection while shooting.

I compared two different sets of lenses for the Oakley Flak Jackets, one which I had used in the Arizona sun for a year, and one which had not seen much use. There was a difference in performance – the unused lenses being better at deflecting angled shots of .22 Short – but in general the Flak Jackets offered less ballistic protection than I would like, and I will be using other eyewear from now on.

If you are a fan of Oakleys and would like ballistic protection too, look for specifically marked Ballistic M Frames, which are on the APEL and offer ballistic protection. However, it appears that they are only available through Oakley’s military sales program, which offers good discounts to active military personnel. I was unable to order a pair of the Ballistic M Frames and could not reach anyone at Oakley in order to acquire some.

For use as shooting eye protection only, I would not recommend any of the products tested in this section.

Absorbing Energy

Some Eye Pro Does This Better Than Others

It’s important to understand another factor when it comes to protecting your eyes. While the lenses themselves may physically prevent fragments or birdshot from entering your eyes, the forces and energy of that shot are still moving towards your face. How the lens – and frame – transmit these forces to your face will affect how much damage is done to the area around your eyes.

This is definitely preferable to having pieces of metal enter your eyeball, but if we can minimize other damage, we should. In extreme cases, the failure to properly protect the eyes from this amount of force could result in loss of vision.

I cannot be certain that the forces placed upon the eye protection I tested – every lens and every shot – were absolutely equal, so I can’t definitively say that X eye pro would protect your eye sockets better than Y eye pro. But I can say that I observed less crushing, tearing, and damage to the styrofoam around the eyes with certain types of eye protection, and certain lens and frame designs, than others.

I noticed that those with solid nose pieces, broad enough to not cut into the skin and not soft enough that they folded out of the way under pressure, distributed force quite well.

In one case, the eye pro was flattened and pushed backward into the face so hard that it sliced the styrofoam head in half. This isn’t likely to happen with a real human head, but it was still unpleasant to think about.

The most gruesome example was the cheap Remington eye pro which shed both lenses back towards the eyes, one of which ended up embedding itself into the eye socket. The real-world implications of this action are unpleasant.

In all, most eye pro with separate lenses did not provide a very high level of protection (Smith Optics’ Director sunglasses were the exception). Not having tested every type, I cannot say whether this extends to all separate lens eye pro on the market. It is interesting to note, though, that almost every type of eye protection on the Army Authorized Protective Eyewear List (APEL) has a one-piece lens.

Another observation was that of the one piece lens eye pro, the versions with a thin or small bridge area invariably failed at this point. This might allow fragments or debris through and will allow more damage to the surface of the face and eyes. The versions with larger or thicker polycarbonate at this point, however, offered higher levels of protection.

Other Eye Pro Factors

There Are Other Things You Need To Think About When Buying Shooting Glasses

By now you should have an understanding of how different types of eye protection perform. There are some basic practical factors you should consider when making eye pro purchases, as well, including:

- Fit – you’ll note in the above photos that the Revision Sawfly eye pro left large gaps between the rear corners of the lens and the “cheek” of the heads. This was also true on my face as well. It would take a lucky shot to get something inside the gap, but it still made me uncomfortable. If possible, you should try on different types of eye protection to see which models offer the best coverage on your face. I found the Smith Optics Aegis models to offer a much closer fit in this regard.

- More fit – I went running with nearly every pair of eye protection tested, and those with soft rubber on the arms stayed in place much better than those without. Also, the smaller/lighter eye pro didn’t move around as much when I ran. This stuff might not matter if you’re only looking for eye protection for use at a static range. If you’re moving around, though, it’s something to think about.

- Scratch resistance – No polycarbonate is immune to scratches. Even the more expensive types, like my Oakley Flak Jackets or the Revision Sawfly, scratched when tossed in a bag with some empty cases and other metal objects and tumbled around for a while. That said, the more expensive eye pro was more resistant to scratches when dust and dirt were wiped off of the lens than the cheap eye pro, which in some cases scratched so quickly that they would interfere with accurate shooting after minimal use.

Summary and Recommendations

What You Should Look For In Eye Pro

I know that this post has been long, so if you’re looking for a simple takeaway, here it is.

Non-ballistic eye protection is fine for keeping relatively slow-moving objects away from your face. Empty cases ejected from a firearm, dirt kicked up by muzzle blast, etc. For faster-moving projectiles such as ricocheted bullets, you need high quality, tested eye pro. I would personally prefer eyewear with a single piece lens for any activity where my face might be struck by small, fast-moving objects.

Individual lenses detach from the frames once a certain level of force is reached, and they are driven back into the eye sockets – sometimes at undesirable angles – where considerable damage may be done. There are good two piece lens eye pro out there, like the Smith Optics Director, but single-piece lenses distribute force much better.

Also, a wide, comfortable, and preferably soft rubber nosepiece is critical. This will, along with good “arms,” serve to keep the eye protection in place during energetic activity – but it will also reduce the chances of the lens being driven down or back into the face at angles or with enough force to damage the orbital bones.

A frame that connects across the top of the lens, not individual arms which attach to the outside corners of the lens, is recommended. This will reduce the chances of the lens detaching from the frame – it’s still possible, just less likely – under impact. Depending on the design, some eye pro with this design also uses the frame to absorb impact and distribute force.

You should also consider how well the eyewear fits you, both in physical dimensions and comfort – and, frankly, whether you think it looks good on you, because you’ll be more likely to wear it if you don’t think it makes you look stupid. Finally, make sure the manufacturer states that it passes MIL-PRF-31013 testing.

Take some time to find the right eye protection for you – and keep in mind that you don’t have to spend a fortune. It’s possible to buy eye protection that meets all of this criteria for as little as $40, which is a pittance compared to losing your vision.